On Monday, after reading about a 15-cent meal in 1944 New York City, I said I was interested in what was served at the cheapest urban restaurants during the first half of the 20th century. I’m still working on this problem, and will be for a little while longer, but I wanted to share with you some of my preliminary findings.

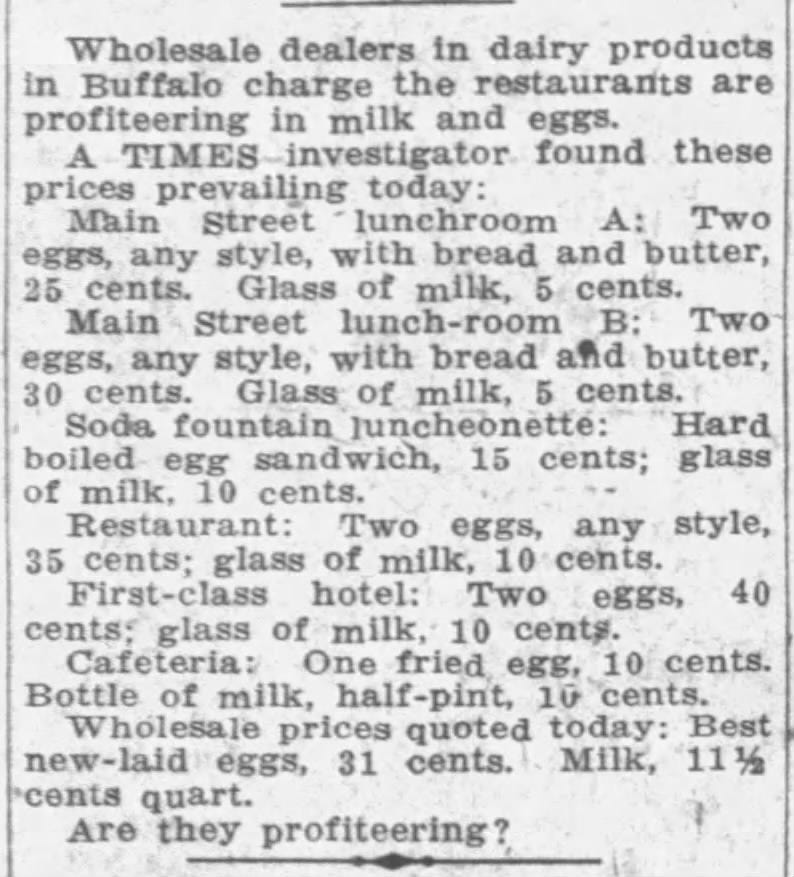

First, I want to establish what prices were like in the 1920’s, so as to give you some sense of how inexpensive a 15-cent meal was in 1944. Here’s a newspaper clipping from the Buffalo Times, May 20, 1921, in which it’s alleged that restaurants in that city are charging outrageous prices for dairy-based meals.

In a cafeteria in Buffalo in 1921, ten cents gets you a glass of milk, or a single fried egg. For 15 cents, you get an egg salad sandwich. Two caveats: first these prices are thought to be somewhat inflated for that year, and are, thus, perhaps not representative. And, secondly, these are not the cheapest of eats. These prices are from restaurants for respectable people, not the down-and-outers.

Fifteen cents for a meal in New York City in 1944, smack in the middle of the economic boom caused by World War II, is mighty cheap, indeed.

Back to the original question, what did you get for your fifteen cents? In truth, the answer to this question took less effort than I imagined it would, thanks to the thoroughness of early 20th century American newspapers, which were filled with accounts such as this one from the Los Angeles Times, dated August 5, 1934.

Dispatched by his city editor to report on conditions in L.A.’s notorious Skid Row, A.C. Faith visited twenty-two flophouses, three missions, five 10-cent restaurants and one all-night theater, and reported back in colorful, concrete detail about what he found. (Let us acknowledge that newspapers used to be enormously entertaining, and that the standard of newspaper writing has fallen precipitously as the formal education of our journalists has increased.)

In any event, for our purposes, Faith’s description of the restaurants is the most important detail.

What do they get to eat for their 10 cents?

My first meal was grease and cabbage soup, not so good; a big hamburger that was fit to eat, a heap of fried potatoes, a piece of fried egg-plant, a small salad of raw carrots and cabbage, white and whole-wheat bread—all anyone could eat of it—a bowl of celeray, radishes and onions that everyone dipped into, a small dish of bread pudding, two glasses of ice tea. Coffee was available.

Not good food, not appetizingly prepared, probably not nourishing from a dietician’s view, but certainly sustaining. All I would expect if I were on the bum and food that I can remember would have been welcome at times in my life.[…]

TEN-CENT MENU

One more menu from the 10-cent: Breakfast—two eggs any style, one hot cake, the invariable stack of bread, fried potatoes and coffee. Lest it be charged that this diet would become monotonous it should be said the dinner provides a choice of about twenty entrees and the breakfast a half dozen.

So, for 10 cents you got soup, entre, side dishes, dessert and a drink. The quality wasn’t the best, the presentation inelegant, but the portions sound adequate. And, thus, we’ve answered our basic question, what did cheap restaurants serve.

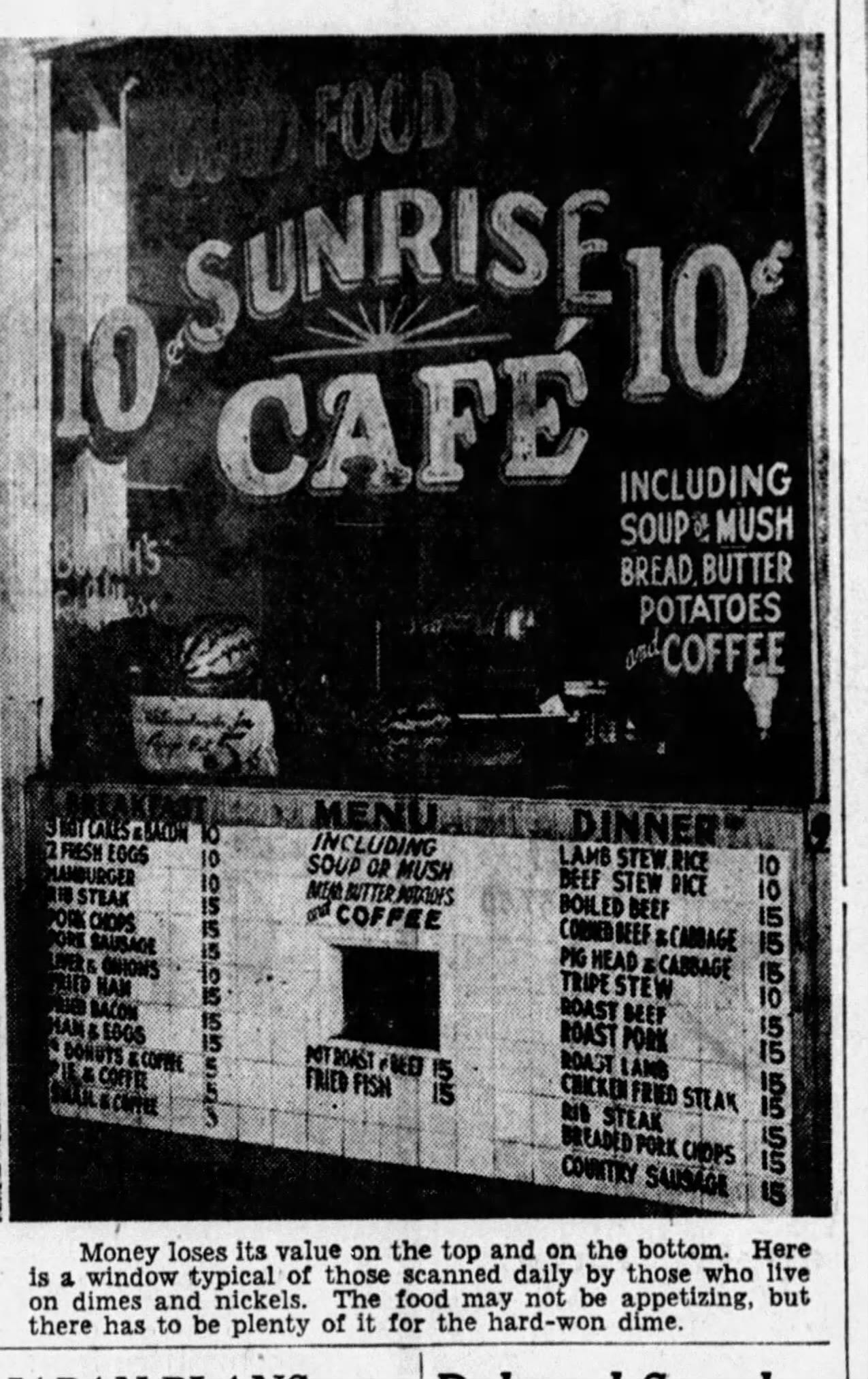

Of course, there’s a lot more to talk about here—including the time L.A’s bums went out on strike and won concessions from the restaurants—but I’m going to save it for another, much longer piece. What I really wanted to share with you was the photo that accompanied A.C. Faith’s article in the LA Times.

And, boom! Just like that we can see exactly what was on the menu at the cheapest restaurant in Los Angeles in 1934: pie and coffee for a nickel, corned beef and cabbage for fifteen cents. Given that clean flophouse beds in Los Angeles were, according to A.C. Faith, 15 cents a night, it was possible to live on less than 50 cents a day during the height of the Great Depression.

One more detail to add, that is, that, for a long time, most of the really cheap cafes on the West Coast were owned by first and second generation Japanese businessmen. This is something I wrote about in the second part of my article, The Great Sushi Craze of 1905, how Japanese cooks dominated the market for cheap meals in the period before World War I. By the Depression, however, competition emerged from restaurants run by Greeks, Balkans, Chinese, African-Americans and others. I don’t know exactly who ran the Sunrise Cafe, nor do I know exactly where it was located, but I’m going to see if I can find out.

So, stay tuned for more about this topic in future posts. Thanks for reading.

Thanks for reading! If you’re not a subscriber, be sure to sure to sign up for twice-weekly updates sent directly into your email inbox.

An Eccentric Culinary History is pretty good description of the general content of this newsletter, eccentric pieces that reflect my odd and wide-ranging interests, primarily culinary and historical in nature. Take a look at the archives for a better sense of what you’ll get twice a week.

Thanks again for your attention and support, and I’ll see you on Monday with something new.

This IS fascinating. That dime would be the equivalent of $2.10, or something like that, today. No way you could this this much of this kind of eats for $2.10 anywhere I can think of today.

PLEASE DO A PIECE ON CLIFTON'S CAFETERIA!!!!