Sometimes, decades later, you realize that something that seemed mundane at the time is, in retrospect, really odd. For example, when I was growing up in Northern California in the 1970s, there were three regional pizza chains built around a Dixieland Jazz theme: Straw Hat, Shakey's and the Gay Nineties. (Yes, the Gay Nineties.) Literally, these were places where you could sit down, order a mediocre pizza and a pitcher of beer and be entertained by a banjo-player dressed in a striped shirt and straw boater.

What was happening here was the conjunction of three post-war American trends: a deep nostalgia for the late Gilded Age, the spread and deracination of pizza, and the incipient growth of franchise restaurants. That's the simplified version, the longer version involves canned tomato sauce, compact industrial ovens, Louis Armstrong, and an ever-expanding class of young men on the make, each trying to come up with the next make-a-million idea. In fact, some of those young men succeeded, succeeded so fully that they actually built a billion dollar industry on the back of Dixieland jazz pizza, and, get this, one of them even exported American banjo pizza to Italy, where, as you will soon see, one of those restaurants is still a going concern.

Today, standing atop the sprawling edifice that is the American restaurant industry, it's hard to imagine a time when pizza wasn't popular. But, prior to World War Two, pizza was barely known in the United States outside of a few Italian enclaves in the Northeast. For all of the praise heaped upon Lombardi’s in New York City, until the war, few people north of Houston Street had heard of it, or the dish it served.

From the mid-19th century forward, there were plenty of Italians in America, in places like New York, New Orleans and San Francisco. Most of those early Italian immigrants—around 75,000 before 1880—were from northern Italy, not the South, and the restaurants they built were usually serving multi-course, table d’hôte meals of meat, bread, macaroni, wine and coffee at reasonable prices. The model was Caffe Moretti’s in Manhattan. Established in 1858 by Stefano Morretti, an ex-seminarian from the Veneto, Morretti’s offered diners generous portions and cheap prices. It did not, however, offer pizzas.

I have to emphasize this, you couldn’t order a pizza in the vast majority of Italian restaurants in America prior to 1945. And the reason you couldn’t order a pizza in Italian restaurants is because pizza isn’t Italian.

Let me repeat that: Pizza isn’t Italian.

Pizza is Neapolitan. It’s a distinct speciality of Naples, developed at at time when Italy didn’t even exist as a nation. Saying pizza is Italian is like saying haggis is British. It might be technically true, but not really.

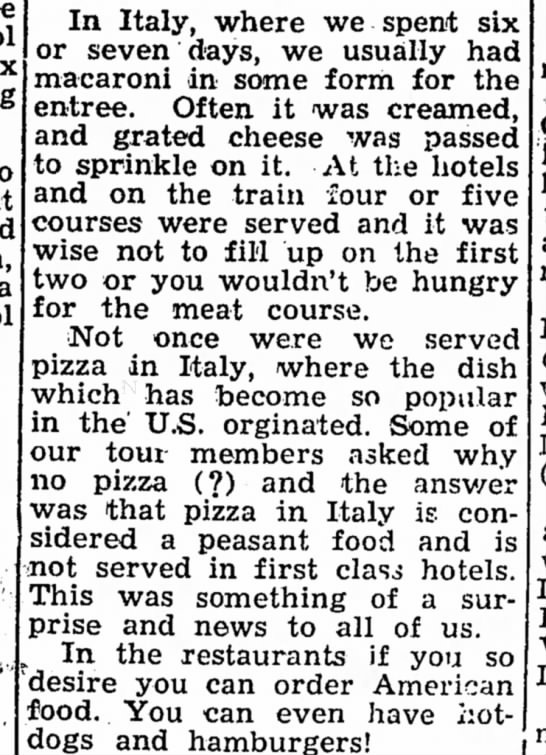

As in America, prior to the 1950’s, pizza wasn’t something most Italians knew or cared about. In 1900, there were supposedly no pizzerias in Italy anywhere outside of the medieval walls of Napoli. You couldn’t even get pizza in the suburbs. Pizza was strictly street food for poor people in the crowded tangled alleys near the port. A small pie cost a penny or two, although if that was too pricey, there was even a system for buying a pizza on time, called oggi a otto, in which if you give me a pizza today, oggi, I will gladly pay you eight days hence, otto.

In other words, pizza was not something the average Tuscan, Ligurian or Venetian would have thought suitable for a sit-down meal. Or, if they ever did think of it, it was to revile pizza as oily, unappetizing and a likely vector of cholera. This is because Naples was really famous at the time for being dirty and disease-ridden. (If you’re serious about early pizza history, one that strips away the just-so stories, then go read Inventing the Pizzeria by Antonio Mattozzi.)

What brought pizza to America was the mass immigration of southern Italians between 1880 and 1910, when more than 4 million people moved to the United States. That’s why Lombardi’s didn’t get going until 1905, when there were finally enough Neapolitans in Little Italy to keep the doors open.

The same dynamic played out in South America, in Argentina, Uruguay and Brazil. The first successful pizza restaurant in the world located outside of Naples was founded in Buenos Aires in 1882, when a Neapolitan immigrant baker named Nicolas Vaccarezza started selling the pies out of his shop in Boca. For reference purposes, a decade earlier, an attempt to open a pizzeria in Rome, Italy, had ended in bankruptcy, meaning, at the turn of the last century, you could get a pizza in Buenos Aries, São Paulo or New York, but not in Rome, Florence or Venice.

The more you look at it, the more you realize that pizza is more American than Italian, in that most of the current popular variations, from deep dish to pepperoni, were developed in the United States and shipped outward to the world. When talking about this dynamic, the food historian Rachel Laudan references the work of anthropologist Agehananda Bharati (née Leopold Fischer) who coined the term “the pizza effect” to explain the process from an anthropological standpoint. Pizza, yoga and Day of the Dead, to name three examples, were all relatively minor parts of Italian/Indian/Mexican culture until outsiders started eating/practicing/celebrating it, at which point the originators reevaluated and readopted the food/practice/festival, usually by incorporating some aspect of the new version. In other words, Americans added pepperoni to their pizzas, went to Italy and started asking Italians where the pizza was, and Italians responded accordingly.

So, pizza didn’t spread to the rest of Italy until the 1960’s, after it had taken off in the Americas. And it happened mostly because American tourists to Italy were desperately trying to find the “real thing” in places where it had never existed, which is why there’s a credible claim to be made that pizza, as it currently exists, is really an American dish.

By the start of the Second World War, pizza had a decent toehold in the Northeast, from Philadelphia to Boston, with a scattering of early-adopters in San Francisco, Miami, Los Angeles and Chicago, mostly Italian places that served pizza as a sideline. There were also one or two oddball spots with their own pizza traditions, such as the Lackawanna Valley in Pennsylvania, where the Old Forge-style pizza took root in the 1920s, thanks to Italian coal miners. Outside of that, pizza was rarely eaten.

That changed after World War II, supposedly when GI’s who’d spent time in Naples came home to the States. Unfortunately, that’s probably another one of those just-so food stories, made up to account for the sudden popularity of the dish. The better answer is that a lot of GIs came home looking to make a fast buck and pizza restaurants, with their high margins, were one place to do that. So, the rise of pizza had more to do with fast money and the U.S. military than with any new-found appreciation for Italian culture.

For this slightly heterodox version of American pizza history, I give you Frank Mastro, “the Johnny Appleseed of Pizza,” a New York restaurant supply salesman who claims to have kicked off the pizza fad in 1936 by developing a compact oven capable of reaching pizza temperature, 600 degrees. By 1957, his firm, Frank Mastro, Inc., was the biggest supplier of pizza ovens in the world, even selling ovens to restaurants in Italy. It was in that year that Mastro gave an interview to the Associated Press in which he laid it all out.

Mastro says pizza first sold like hot cakes in New York’s German neighborhoods, “not in the Italian neighborhoods because Italians don’t go much for eating out.”

“During the depression, a guy could get a whole pizza for a quarter and make a meal out of it while the owner racked up 90 percent profit”

The big break came during the war, when thousands of soldiers passed through New York and tasted their first pizza.

Pizzerias appeared outside Army camps and Navy bases, then a lot of Italian boys from New York came home and decided to go into the pizza business in various towns where they had been stationed.

New York, not Napoli.

A lot has been written about the growth of fast food franchises in the post-war era, most if it focused on improved transportation networks and the systemization and standardization of food production, but not a lot has been written about young men on the make. Yet, it’s those young veterans looking to make a fortune that drove the America fast food industry at its inception. For example, Glen Bell of Taco Bell had been a cook in the Marine Corps, and Harry Snyder of In-n-Out, an Army supply sergeant. Both mustered out of the service and into the restaurant business in California, which was ground zero of the fast food explosion.

The post-war circumstances that enabled the rapid growth of American fast food are well known: cars, freeways, baby booms, industrial systems and money. Thanks to books like Fast Food Nation, that’s old news. Instead, I want to explain why a small number of these young men decided that pizza needed to be associated with banjo music and how this odd choice made several sizable fortunes in the restaurant business.

The key to understanding Dixieland Jazz pizza is understanding that pizza is not just food, pizza is entertainment. A hamburger and hot dog are portable grub, pizza isn’t. Yes, Neapolitan pizza was largely a stand-up meal for people who barely had shoes. You bought it in the street and ate it in the street. But in America, outside of New York City with its pizza-by-the-slice, pizza is a sit-down meal, a remarkably convivial sit-down meal. Two to ten people can sit at the same table and eat from the same dish with their hands. Pizza is inherently fun. Pizza is entertaining.

The post-war pizzerias, the ones started by Frank Mastro’s Italian-American boys, and the GI’s who imitated them, all drank deeply from a well of cartoon Italian-ness. They played up their supposed connection to Bella Italia with checkered table cloths, chianti bottles with candles and stereotypical Italian imagery, like the Leaning Tower of Pisa or the Colosseum, never mind that there were no pizza restaurants in Pisa or Rome.

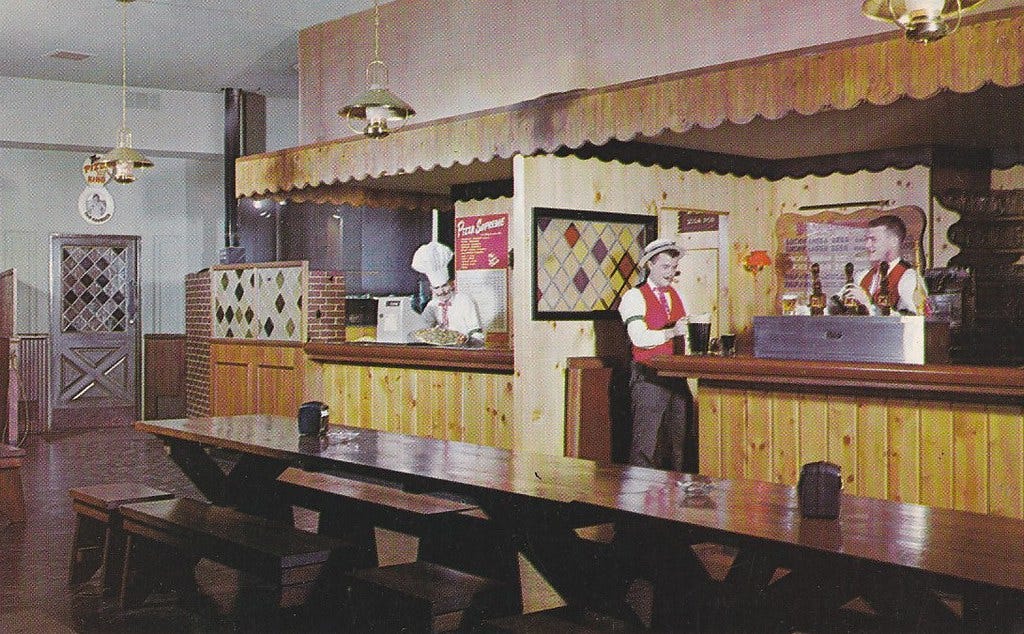

Enter Sherwood “Shakey” Johnson. Shakey was a veteran of World War II, a sailor who got his nickname from a bout of malaria contracted while serving on a Liberty ship in the South Pacific. The disease gave him a temporary case of the tremors and a permanent nickname. In 1954 he had a brainstorm, make pizza even more entertaining, or… as some have suggested…he just wanted to have a place to play his piano and an audience to listen to it. Either way, in 1954, Shakey opened his eponymous restaurant at 57th and J Streets in Sacramento: pizza, German beer and “old-timey music”. It was an immediate smash hit. Within six months, Shakey was forced to double the size of his restaurant to keep up with demand; within six years, he had nearly 40 stores up and down the West Coast, and by 1970, there were more than 300 nationwide.

Live music was only part of the deal. Unlike every other pizzeria in America, Shakey and his employees made no attempt at authenticity. Forget Italy, this was “American style” pizza served in a mock English pub.

“We don’t pretend that it’s Italian,” said one franchisee, echoing the corporate line, “it’s Shakey’s own….We have American Pizza with German beer served in an Olde English Atmosphere.”

In an instant, pizza had been deracinated, ripped from its roots and worked into a exuberantly artificial, wildly idiosyncratic, commercial entertainment product. Shakey’s was a fantasy land devoted entirely to make-believe—Baudrillard’s head-spinning hyperreality—and this a full year before Disneyland opened its doors!

Paradoxically, at Shakey’s, everything was fake but the music was real—live bands playing hot licks—and the pizza was pretty good, or at least I remember it as being pretty good. It’s been a long time. But, it’s the music that really set Shakey’s apart. Banjo and upright piano playing old-fashioned classic American songs—Dixieland, ragtime, barbershop, Gilded Age standards—and you were encouraged, practically obliged, to sing along. Later, the menus even had lyrics printed on them, so you had no excuse. It was hilarious fun, even into the early 70’s, a wholesome, goofy, wholly American sort of thing, lubricated with decent German beer and pitchers of soda for the kids.

Shakey’s music program was so successful that it kicked off a Dixieland jazz revival on the West Coast, one that eventually led, in 1966, to Walt Disney adding New Orleans Square to Disneyland, simply because Dixieland music had become such a big draw. There was even a band composed of Disney animators, the Firehouse Five Plus Two. And, lest we forget, in 1964, Jerry Herman’s Hello Dolly premiered on Broadway, the faux Gilded Age musical romp that gave Louis Armstrong his biggest hit ever. It was, as they say, a cultural moment.

Of course, the success of Shakey’s naturally spawned imitators in Northern California. As best as I can tell, the Gay Nineties chain got going in 1959 in Pleasanton, where one of the last surviving stores is still in business. While in 1960, Straw Hat opened it’s first restaurant in San Leandro, in the Bay Area. There were plenty of other long-forgotten banjo pizza parlors that popped into existence around the same time, like Me n’ Ed’s in Redwood City, Hambone’s in San Mateo, the Blue Banjo in Redding, and Mr. Banjo’s in Van Nuys. By 1963, you could find banjo pizza in places like Fort Worth, Cape Cod, Chicago and…Florence, Italy.

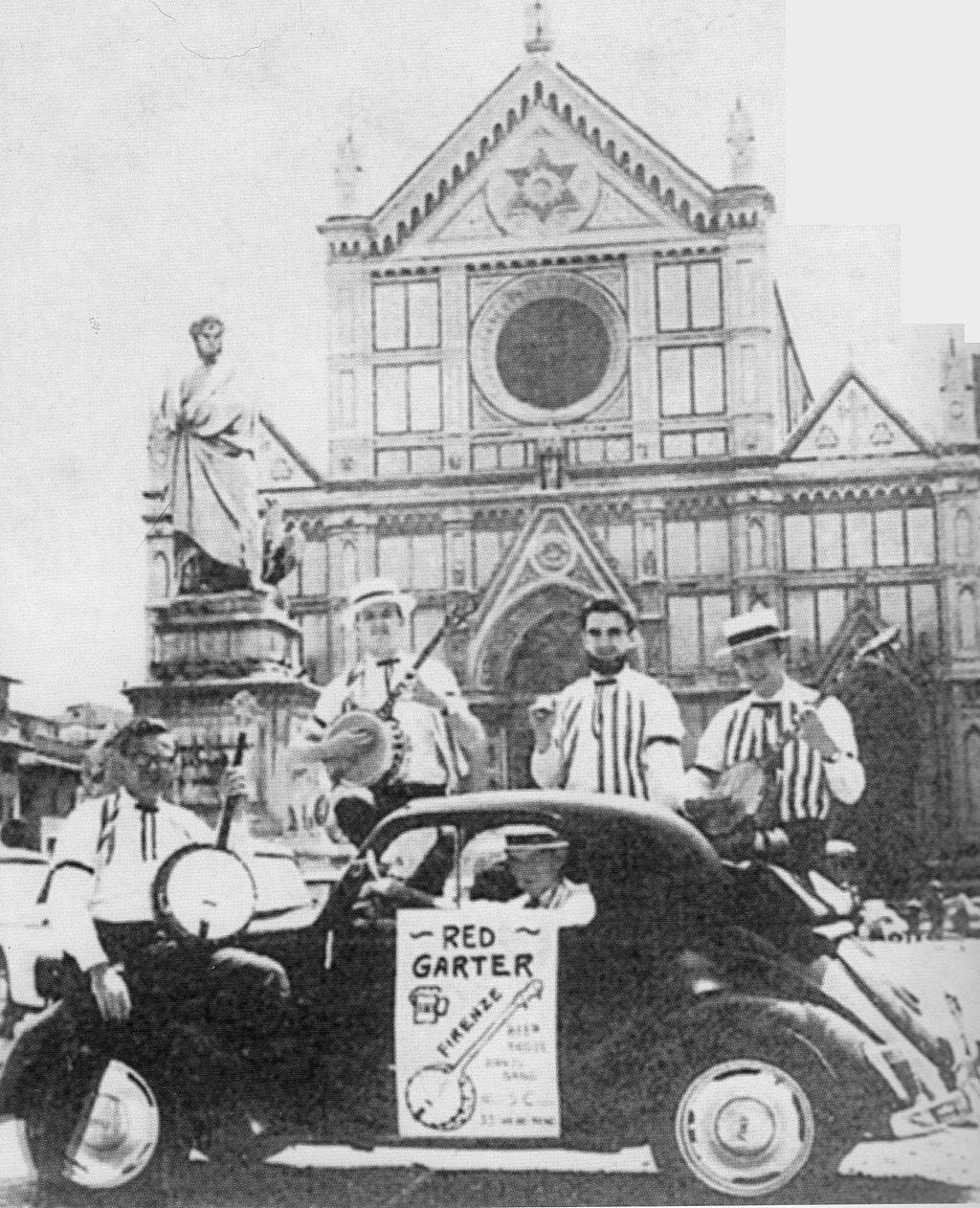

And this, finally, is the crazy Pizza Effect payoff of this long story: in 1962, an American businessman successfully exported banjo pizza back to Italy, and that restaurant is still in business in 2022! It’s called the Red Garter, and it’s directly across the street from the Santa Croce church, a block from the Arno River. There’s even a branch, now, in Barcelona, Spain.

The person responsible for this magnificent piece of cultural imperialism was a young, Harvard-educated medievalist named Jack Correa, who on one of his many trip to Italy noticed that there were thousands of America students studying abroad in Florence every year, with few pizza parlors (see above) and no banjos in sight.

So, Correa took a franchise from San Francisco’s now defunct Red Garter chain (founded in 1958) and planted his flag. And it worked. As the San Francisco Examiner said, Italians were “seeing for the first time American-Style Pizza in its paisano motherland.”

Jack Correa’s banjo pizza took root in Italy, or at least Florence, and prospered. Although, by the time Jack sold his restaurant in the early 70s and moved back to America, the Neapolitans were fighting back, reclaiming pizza for themselves. After that, somewhere along the way, the Red Garter gave up selling pizza and turned into an American diner, with steaks and hamburgers, Dixieland jazz having long been replaced by rock n’ roll. It is, however, still one of the most popular hangouts for American students in Florence.

While banjo pizza is mostly just a distant memory in its homeland, America.

P.S. Here’s something else that may entertain, a few thousand words on the history of poultry farming in California.

The Shakey’s in Dallas, at least, in the early 60s had the kitchen in the middle and on the larger side served beer, but us kids had to go to the smaller side which was dry. Liquor and evidently beer rules were strange in those days in Texas.

Later living in Houston, in the mid 70s, I would pick up Shakeys to go and take to my GF’s apartment. The carry out box hadn’t been perfected, and was only corrugated cardboard flat sheets held together on the sides with a primitive and ineffective tab system. Driving home in my new Triumph TR7, I placed the pizza on the console and attempted to hold it down with my right elbow. Taking a S curve, without slowing down, the pie slid out of the box and landed on the passenger seat, the still bubbling cheese going further afield than the crust. The dairy product fused itself to the fabric. Never was sure if was petrified cheese on the seat, or melted synthetic fabric, but the scar was never removed.

When I was a teenager, back in the 70s, my parents would take us to Shakey's a lot. It was a treat because, unlike hamburgers and hot dogs, you really couldn't make decent pizza at home back then. I don't recall much about the pizza but we were all addicted to those Mojo potatoes. The thing about kid's pizza is that parents usually kept it simple. They would usually order a pizza with pepperoni. (or a pizza where the other half was just cheese if someone didn't like pepperoni.) Then in college I was exposed to the Chicago style with tons of toppings. Usually now, the only time I have pizza is when they throw a pizza night at work where the bosses buy a bunch of cheap pizzas for us with a selection of pizzas with various toppings. (And get criticized at by the vegans for not having any decent vegan options.)