In my last post, “California’s Vanishing Lakes and the Hunger of the Mines”, I made frequent reference to the one dollar eggs of the Gold Rush, a staple of 49’er anecdotes and 19th century California culinary history. In fact, while doing the research for what would turn into a 5,000-word article, I found more information about eggs and poultry than I could use in a single piece. I put much of this research aside for a later project, although, one question kept sticking in my mind:

Why hadn’t a sustainable poultry industry appeared in California earlier than 1880?

I cite 1880, three decades after the Gold Rush, because that’s when Petaluma, the self-proclaimed “Egg Capital of the World”, really got going, taking off after Canadian immigrant Lyman Byce invented the temperature-controlled incubator in 1879.

This evident slowness to capitalize on the demand for eggs and chickens is odd, because everyone in the Western Hemisphere, from the King of Hawa’ii to the hacienderos of Chile, cashed in on shipping food to California, while local farmers in the Bay Area made fortunes on fresh vegetables. In comparison to poultry, the demand for beef and the consequent high prices for cattle (whose per head value jumped nearly 2000% between 1848 and 1849) gave rise to the empire of Henry Miller, the cattle baron who by 1878 controlled a million acres of western land and the water rights to most of the San Joaquin Valley.

For eggs and chickens, however, the commercial explosion happened a generation later, after the Gold Rush had ended.

It was not because chickens were completely unavailable in California. Mary Ballou, a New Hampshire woman who kept a boardinghouse near Sacramento, wrote a letter in the fall of 1852 to her son in which she mentioned feeding the chickens in her backyard, and serving roasted birds at four dollars a head and eggs at three dollars a dozen. Likewise, there are many other references to kitchen-yard hens in the letters and diaries of the era.

Yet, eggs remained stubbornly expensive in California, so much so that hen’s eggs were being shipped from as far away as Chile, the Eastern United States and China well into the early 20th century. This, even though by 1910, Petaluma was already producing more eggs than anywhere else in the world, making it one of the richest cities in America per capita.

The slowness of commercial egg farming to develop in California was also not because entrepreneurs hadn’t tried to start chicken farms, it was just that none of them had succeeded until the late 1870s. Until that point the demand for fresh eggs was largely satisfied (to the extent it could be) by importing eggs from great distances, or by seabird eggs, gathered from the giant (but fast declining) colony of murres that roosted on the Farallon Islands, 30 miles due west of San Francisco.

The artist Eva Chrysanthe, who is working on a fun graphic novel about Italian immigrants and egg collecting in the Farallones, Garibaldi and the Farallon Egg Wars, states the problem well.

By now, we all know that the 19th-century poaching of murre eggs on the Farallon Islands was spurred by the lack of poultry – and thus a dearth of eggs – in San Francisco. But few people have been able to explain why there was no poultry industry in San Francisco.

.It’s conceivable that all existing chickens in Yerba Buena had been consumed in the first year of the Gold Rush, given the arrival of tens of thousands of men to a town whose population had stood at only 1,000. But why was there no effort to restock the yards? Were chickens simply not hardy enough to make the lengthy sea voyage to San Francisco? If so, could no chickens be carried overland from Mexico?

Chrysanthe thinks she’s solved the riddle by quoting an excerpt from Sebastian Fichera’s book, Italy on the Pacific: San Francisco’s Italian Americans, about an Italian immigrant named Pier Giuseppe Bertarelli who failed to make a go of it as a poultry farmer. Here’s Fichera on Bertarelli:

In April 1852, after escaping yet another fire, he made an auspicious start on a new scheme, raising and selling chickens at three dollars apiece. Though admitting, in his correspondence, that he was now spending most of his time looking through garbage dumps in search of feed for his chickens….

the summer of 1852 seems to have been the high point of Bertarelli’s California adventure. But it proved to be just another illusion: his unlucky star, this time in the form of a plague killing off all his chickens, caught up with him again and his resolve to stick it out began to falter.

For Chrysanthe, the absence of chickens is attributable to their vulnerability to disease. And, indeed, when crowded together chickens are susceptible to various avian plagues, which is one reason why modern battery hens are continually dosed with antibiotics. It’s also possible that chickens brought from elsewhere might not have had immunity to the diseases of California wild birds, causing the die-offs that are occasionally mentioned in California farming journals.

I think, however, there is a more fundamental reason why the egg industry didn’t take root until three decades after gold was discovered: it wasn’t profitable enough.

The clue to the insufficient profitability of local hen’s eggs is not the poultry disease, it’s that the hapless Signore Bertarelli was searching garbage dumps for chicken feed.

A few chickens kept behind a boarding house can live on kitchen scraps and pecking around for insects. Several hundred hens can’t do that. Feed has to be purchased in bulk, and chickens eat things that humans also consume — vegetables, corn and grain — all of which commanded premium prices in Gold Rush San Francisco, hence the need to scour the garbage dumps for scraps. In fact, chicken feed was so expensive that Boston eggs, shipped around the Horn, and murre eggs from the Farallones were cheaper than hen’s eggs after the cost of feed.

In other words, egg farming couldn’t be scaled up to commercial production. At least not until the murres were depleted and grain and produce prices dropped.

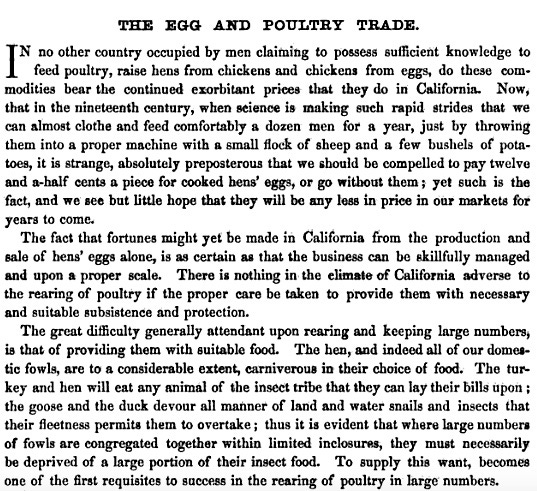

In 1859, the editor of the California Culturist, a new farming journal debuting in May of that year, urged his readers to take up chicken farming, promising that fortunes might be made from “hens’ eggs alone.” Similar opinions appeared regularly in American poultry journals until at least the 1890s. But the biggest problem to overcome was always the same, the economics of expensive feed and competition from nature and elsewhere.

As for chickens for the table, a similar dynamic was likely in place — domesticated birds were more expensive than wild birds or birds shipped from the East Coast.

Prior to the mid-20th century, when the broiler industry took off in America, the majority of chickens were dual-purpose birds, like the Dominque above, raised in barnyard flocks for both eggs and meat. The cockerels were eaten young, roasted or broiled, and the tough old hens stewed after they’d stopped laying, usually around eighteen months. Hens would rarely have been eaten before that, especially not in California where eggs were so valuable.

It’s well known that until recently American’s didn’t eat that much chicken reserving the bird for special occasions, holidays or the odd Sunday dinner. In fact, as recently as 1978, Americans were still eating twice as much beef as chicken per capita (87.1 lbs of beef annually versus 44.7 lbs of chicken), and not until 1992 did chicken finally surpass beef as the American protein of choice. (The story of how we were converted to chicken-eaters is a good one, and perhaps someday I’ll tell it.)

Mostly, if pressed, people who think about these things will say that Americans didn’t eat chickens because the birds were valued more for their eggs than meat. But that’s not true.

Europeans ate both plenty of eggs and plenty of chickens. For example, Eastern European Jews, forbidden pork by their dietary laws, favored chicken meat. The development of the American broiler industry in the 1920s was, to some extent, a by-product of the Jewish immigrant taste for chicken, especially on the Delmarva Peninsula where kosher chickens were grown for the New York market. (After 1905, there was also a large community of Jewish egg farmers in Petaluma.) Likewise, from the 18th century forward, the French ate chicken avidly, and by the middle of the 19th century, French farmers had figured out how to mass produce eggs, capons, and young hens, poulardes, for the table. Some of these ingenious farmers got very rich.

Americans didn’t eat much chicken not because they didn’t like it, but because in North America, and especially in California, the conditions and economics were against it: other forms of meat were easier to produce and market, and game abounded, especially game birds.

Chickens are small, delicate, highly-evolved creatures. They must be housed at night to protect them from foxes and they’re susceptible to heat stroke, frost bite, the common cold and a grab bag of exotic ailments. In their favor, however, they will eat almost anything, although it must include odd things like calcium for shell formation, and somethings, like corn, must be milled to be edible.

And, crucially, chickens can’t be herded hundreds of miles to market; they couldn’t walk themselves into California, as cattle and sheep did in the 1850s, nor walk themselves to slaughterhouses on the edges of the cities.

The high value of eggs pushed American farmers to try to overcome some of these limitations, but beef and pork were still cheaper, as were game birds, especially in California where the Pacific Flyway brought tens of millions of waterfowl into the state each year.

Because the great wetlands of California had not yet been drained, their sources channelled into irrigation, massive flocks of waterfowl — ducks, geese, teals. swans, cranes — still landed within shotgun range. And, market-hunters outdid themselves by bringing these birds to the table right up until the beginning of the 20th century when bird populations plummeted and the market hunting of migratory birds was outlawed.

One of the figures who helped bring an end to legal market hunting was William Temple Hornaday, a Smithsonain taxidermist turned conservationist, and the first director of what would become the Bronx Zoo. Starting in the late 1880s, Hornaday wrote and spoke extensively about protecting American wildlife, using every opportunity to harangue Americans about overhunting. By 1910, Hornaday and other conservationists had had conspicuous success in saving such iconic species as the pronghorn antelope and the American bison (which Hornaday had personally rescued from extinction).

But, there was still plenty to do, and in 1913, Hornaday published, Our Vanishing Wildlife: Its Extermination and Preservation, a call to action for Americans who loved their native animals. Heavily illustrated with photographs and written in a clear, emphatic style, the book was a sensation with the American public, and led directly to the passage of the Weeks-McLean Migratory Bird Act of 1913, which federalized waterfowl protection, outlawing the killing or sale of endangered species. Hornaday, himself, testified at the hearings, distributing copies of his book to lawmakers before his appearance.

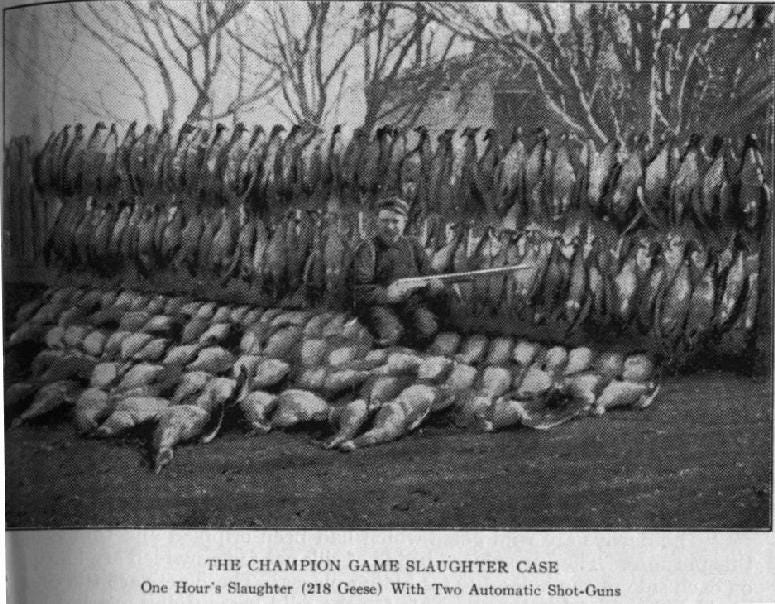

Here’s an example, taken from Our Vanishing Wildlife, of the sort of damage a single pair of market hunters could do in a single day in California.

Very many enormous bags of game have been made in a day by market gunners: but rarely have they published any of their records. The greatest kill of which I ever have heard occurred under the auspices of the Glenn County Club, in southern California*, on February 5, 1906. Two men, armed with automatic shot-guns, fired five shots apiece, and got ten geese out of one flock. In one hour they killed two hundred and eighteen geese, and their bag for the day was four hundred and fifty geese! The shooter who wrote the story for publication (on February 12, at Willows, Glenn County, California) said: “It being warm weather, the birds had to be shipped at once in order to keep them from spoiling.” A photograph was made of the “one hour’s slaughter” of two hundred and eighteen geese, and it was published in a western magazine with “C.H.B.’s” story, nearly all of which will be found in Chapter XV.

With market gunning not just continuing into 20th century, but getting more efficient with automatic shotguns, is it any wonder that California restaurants charged more for chicken (or three eggs!) than wild duck or goose? Or that chicken was often the most expensive item on the menu?

By the 1880s, when William Temple Hornaday (who had once shot 24 orangutangs on a scientific trip to Borneo, bringing home enough skins to have “carpeted a good-sized room”) converted to conservationism, the collection of murre eggs was already on the wane. In 1854, 500,000 murre eggs had been taken to San Francisco; in 1886, the take was a fifth that size, 108,000 — only 9,000 dozen — sold at 12 cents per dozen.

At the same time, California chicken ranchers had finally figured out how to profitably raise chickens in California. In 1879, 5.77 million dozen eggs were grown in the state; in 1889 – 13.68 million dozen; and in 1899, 24.44 million dozen. Although eggs from elsewhere continued to be brought in, with nearly 2.5 million dozen shipped in from the Midwest in 1890.

What was the secret to raising hens in California? Interviewed in the Rural New-Yorker in 1898, Petaluma poultryman C. Nisson (author of the book Nisson on Incubation) said it was the “California slipshod method” that had succeeded where the more intensive and “scientific” methods imported from the East Coast had left behind nothing but Ozymandian ruins.

-“Eastern people do not see how California poultrymen can help getting rich on these prices, and if they don’t, it must be because they don’t know how to manage. So they will rush over here to make the money which we California henmen have not the wit to make.”

-“Well, how do they usually come out?”

-“Within ten miles of my farm, are two large poultry plants, started a few years ago on the true eastern methods. Everything was calculated and figured out before starting.”

-“Where are they now, planted?”

-“Only the ruins of these large poultry farms are to be seen. Probably their owners have sunk $100,000 in these few years. At the same time, within the same distance, I can count a score of poultry farms were from 500 to 5,000 hens are kept in the seemingly slipshod fashion of California. But these are all doing well. They are not getting rich very fast, it is true, but they make good wages and have a good time.”

What was the California slipshod method? In a word, free-range. Nisson’s version of the practice involved colonies of 100 mixed-age birds in mobile coops, moved a couple times a month onto fresh ground in fields planted with barley or corn. There were no fences, lots of room to peck and scratch, and regular delivers of water, grain, soft mash and “meat, beans, peas, potatoes, and whatever else we have or can buy, cooked or uncooked, as seems best.”

-“Then your so-called slipshod California method consist chiefly of making the hen take care of herself.”

-“That’s just about what it amounts to.”

In other words, the solution to the high cost of feed in California had been to replicate kitchen-yard chickens on a grand scale!

***

*Glenn County and the town of Willows are not in Southern California, but in Northern California, 70 miles north of Sacramento, a couple dozen miles from where I grew up.

P.S. From the always amusing Henry Vogt comes this two-year-old post (with menus and prices): Fresh Eggs in California.

Interesting article, thanks. But those were not "automatic" shotguns. They were semi-automatic with one shot for each pull of the trigger, not a continuous stream of shots with a single pull.