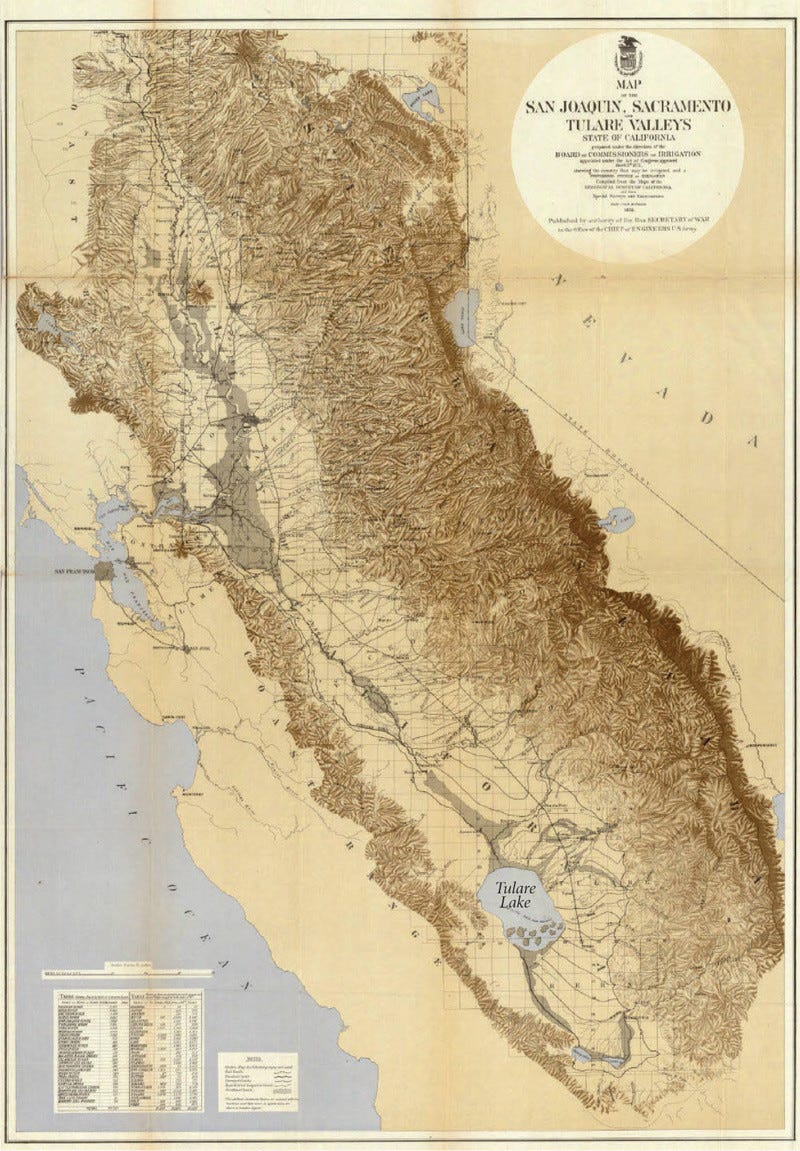

If you drive the long stretch of Interstate 5 known as the Westside Freeway, from the foot of the Grapevine through Buttonwillow and on to Los Banos, you’ll be cruising along the edge of the richest and most productive farm land in the world. If, halfway through that journey, you stop at a place called Kettleman City (a name more ambitious than accurate) and stand at the edge of the parking lot behind the In-and-Out Burger looking due east down a gentle slope, you’ll be staring at what was once the largest freshwater lake west of the Mississippi River.

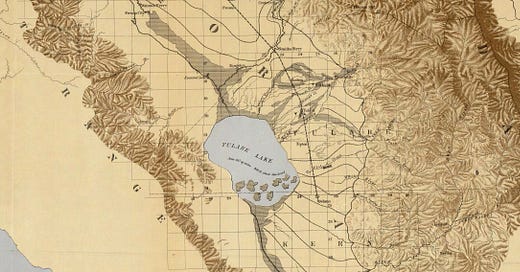

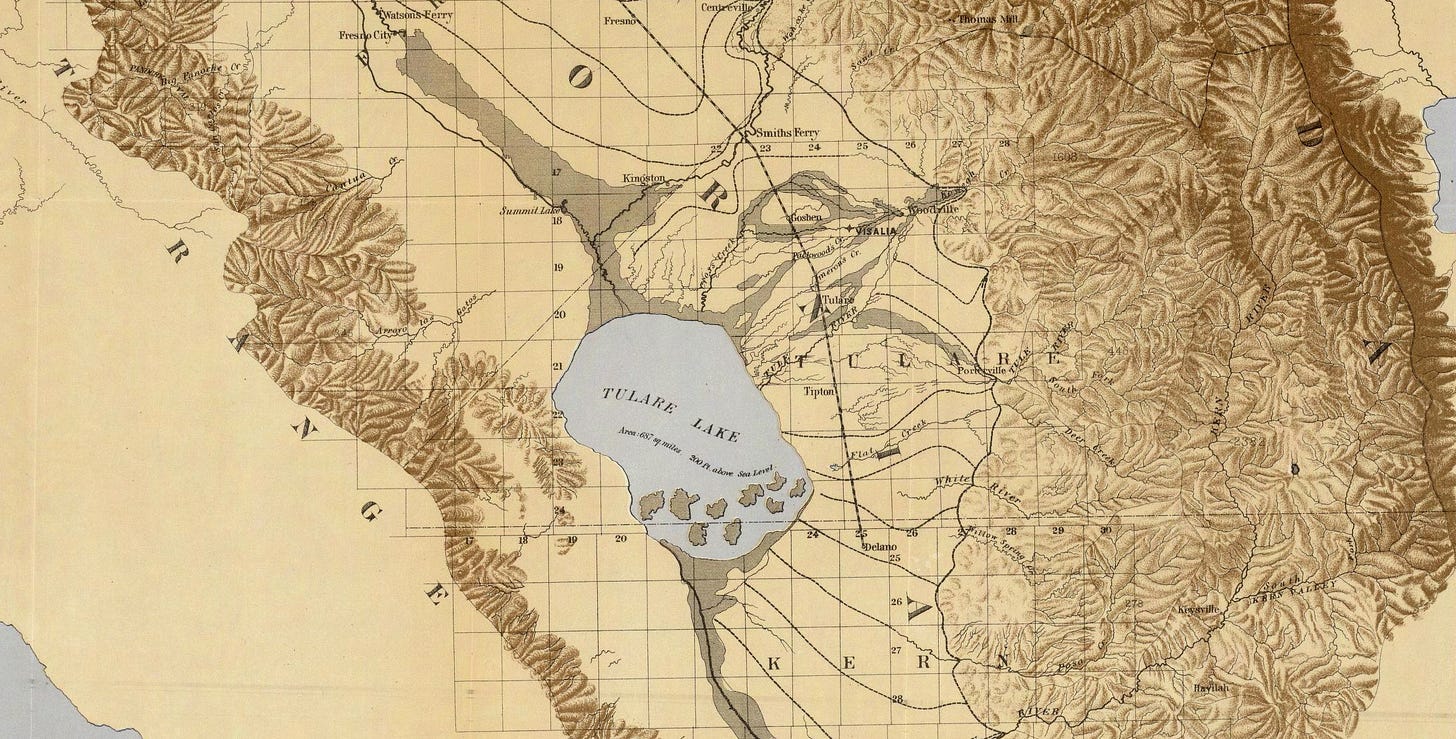

course, from your perch at the In-and-Out, you won’t see any water. Tulare Lake is long gone, all 700 square miles of it; its water restrained behind dams in the foothills and channelled away into the irrigation canals that make the Central Valley so productive. In its place are hundreds of square miles of cotton and corn, and an elaborate system of drains, ditches, channels and sumps designed to keep the lake bed farmable.

The massive rearranging of California’s water resources, which began with the Gold Rush and continues to the present day, is a triumph of ingenuity and engineering, and the utter destruction of the original, pre-1849 biome.

Before to the discovery of gold, the Central Valley was far wetter than it is today. In a sense, the valley respirated water, breathing in during the wet seasons and breathing out during the dry. In winter when the rains came and in spring when the snow melted, water poured into the valley, swelling the rivers and filling the low places with seasonal lakes, bogs, potholes and vernal pools. When the rains stopped in late spring, and the weather turned hot, the remaining water evaporated and the grasses dried up.

The hydraulic system of the Central Valley has three main zones: the Sacramento Valley, the northern San Joaquin Valley and the southern San Joaquin Valley, also called the Tulare Basin. Water from the two northernmost zones flow into San Francisco Bay via the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers which meet east of the bay in the Delta, the largest estuary in the western United States. The third zone, the southern San Joaquin Valley, is usually endorheic.

Before the replumbing of the rivers, in most years water did not leave the Tulare Basin. In wet years, however, Tulare Lake overflowed into the San Joaquin River, sending water up through the Delta and out the Golden Gate. There were two other lakes at the far southern end of the valley, Kern Lake and Buena Vista Lake, both now drained away by canals and dams. During the wettest years these lakes would also overflow, linking up with each other and Tulare Lake to form a single, vast body of water. The missing lakes and the tens of thousands of acres of tule swamp and grassland that ringed them thus waxed and waned with the seasons, part of a complex ecology that supported enough fish, fowl and fauna to make it one of the richest biomes in the world.

The arrival of the Spanish settlers to California in the 18th century did little to upset the natural arrangement of the Central Valley. Beyond stock grazing, the californios had little interest in the interior of the state; it was too far from the coast and too hot in the summer for their tastes. Better to stay in Monterey and Santa Barbara and let the indios have the Central Valley.

For their part, the natives of the Central Valley were content to hunt and gather rather than cultivate. Acorns from the oaks that lined the creeks and rivers were gathered in baskets and stored in holes until needed. Birds and wild game were hunted with throwing sticks and bows and arrows, or trapped in snares. A simple wicker fish weir in a creek yielded hundreds of pounds of salmon during the spring and winter runs. This bounty, when dried, could feed the tribe for months. (In the wet years, the salmon even made it from the San Joaquin River into Tulare Lake, to the great joy of the Yokut who lived in the tule reeds along its banks.)

As one wag has said, if the pilgrims had landed in California instead of Plymouth Rock, the rest of the country would never have been settled. Indeed, the Anglos who began to enter the state in the early decades of the 19th century — Yankee merchants, run away sailors and fur trappers — were dismissive of both the californios and the indians, and for the same reason, because they were insufficiently industrious, content to herd cattle or fish salmon rather than develop the land to its “full potential”.

The modern settlement of the Central Valley began when Americans started to arrive overland via the Oregon Trail in the 1840s. Many of these newcomers became Mexican citizens, took Mexican wives, and received Mexican land grants along the Sacramento, Feather and American Rivers, grants that were measured in Spanish leagues (4,428 acres), of which five leagues would be considered the usual size. By 1846, when the last of the Mexican land grants were made, much of the Valley had been parceled out.

As for the people who were already there, perhaps half of the Central Valley indians died in 1833, a year after mountain man Ewing Young led a group of trappers through the valley, inadvertently spreading malaria as they went. Parts of the valley were “virtually depopulat[ed]” by the disease, and the survivors left scattered, weakened, and easily pushed aside or exploited by the American settlers. By 1845, the number of indians in all of California was probably 150,000, about half of what it had been when the Spanish arrived 70 years earlier. Fifteen years later, in 1860, a dozen years after the discovery of gold, there were only 50,000.

All of this, however, is prequel to the real topic, why California landscape and wildlife are so radically different from what they were, and why the biggest changes happened in those dozen years after 1848.

Most accounts of the environmental damage caused by the Gold Rush focus on the easily explained, direct effects of mining. Washing away entire hillsides with water monitors sent mountains of debris into the rivers; processing the resultant slurry with buckets of mercury poisoned the soil. However, the most lasting changes to California’s waterways, landscapes and biomes were caused by trying to feed the miners and settlers.

100,000 newcomers headed for California in first year and half of the Gold Rush, 50,000 in the first five months came overland from the United States, alone, and much has been said about the famously difficult trip they endured. Less has been said, however, about the difficulty of feeding all of those men in a place where there were few farms or fishing boats, most of which, in any event, were abandoned minutes after the news of gold was announced.

Popular food histories of the Gold Rush are always a fun read, with their stories of Hangtown fries and chop sueys, and their lists of outrageous prices — of when eggs were a dollar each, and a piece of bread could be purchased for another dollar, two if buttered. The best and best researched in this genre is a book by my old Chico State historiography professor, Joe Conlin, whose 1986 Bacon, Beans, and Galantines: Food and Foodways on the Western Mining Frontier is a hilariously readable collection of Gold Rush food histories, and a work which includes the following little gem:

One prostitute of legend delighted herself when, in one season, a garden she kept behind the cribs netted a fifty thousand dollar profit, enough to transform any soiled dove into a bourgeoise angel.

A sentence worthy Herbert Asbury, or the supremest and grandest of the E Clampus Vitus Supreme Grand Humbugs. And yet, however apocryphal that story may be, it points out that for a while, at least, fortunes were to be made growing and selling food in California, especially in selling.

One dollar eggs, which you may now purchase hard-boiled at your local convenience store, continued to shock readers right up until the 1990s, when inflation finally caught up with the Gold Rush prices. Today, adjusted for inflation, that one dollar egg would cost $30.30. But that’s not right, because in Massachusetts in 1850, on the other side of the continent from California, a skilled mason earned about $1.75 for a day of hard labor, suggesting $120 eggs.

Just as stories of giant nuggets lying in stream beds exercise a powerful pull on some men, stories of one dollar eggs and $50,000 gardens do so on others. The latter, who are fewer in number, tend to be men smart enough to know that the real money is in selling shovels and eggs to miners. Luckily, food history, as a practice, is capacious enough to allow us to follow the logistics trail of the Gold Rush from start to finish, i.e. from where did the one dollar eggs come, and what was the effect of one dollar eggs on the environment?

The answer to the first question, initially at least, was the Farallones, an archipelago of rocky islands thirty miles due west of San Francisco, where giant colonies of the common murre laid their eggs.

In 1849, a pharmacist and would-be theatrical impresario from Maine named David Robinson scrambled up the sides of South Farallon Island and gathered enough of the murre eggs to make $3,000 in one go, this despite breaking half of his cargo on the trip home through rough seas. San Francisco diners soon discovered that murre eggs were not only more than twice the size of a hen’s egg and had bright red yolks, but were also delicious. And, thus, the great Farallon Islands egg rush was on. Within a year, a group of rough-and-ready entrepreneurs had laid claim to the best egging grounds on the Farallones and begun the process of pulling more than 500,000 eggs a year off the islands.

And in answer to the second question, even though egging on the Farallones was outlawed in 1896, the common murre population has still not recovered.

As the tale of apocryphal lady of pleasure illustrates, growing crops also turned out to be profitable. By 1850, farms in the Bay Area and the Delta were producing prodigious profits growing crops to feed the ever-expanding army of miners. By the end of 1851, John Horner, a Mormon farmer in San Jose, reported a gross cash income of $175,000 from cabbage, onions, tomatoes and 35,000 bushels of potatoes grown on his 160-acre spread, an amount of money that would be considered a respectable showing even today. (In 2015, the average yield of an acre of corn is 160 bushels, sold at an average price of $4 a bushel, or $640 an acre gross income. Potatoes and cabbages fare much better, averaging $3000 and $8,500 gross per acre, respectively, although they also have higher input costs.) Horner used his profits to invest in more land, found Union City, California, and buy a steamboat.

In addition to being locally grown, food was being imported from great distances and selling at marvelous prices. I recently spent three months in Chile, and while doing preliminary research for a book on Chilean food culture I repeatedly encountered the transforming effects of the California Gold Rush on Chilean history.

News of the strike at Sutter’s Mill reached Santiago in August of 1848, weeks before it made it to New York, and Chilean miners, who had three centuries of experience chasing gold and silver, rushed to California, arriving before almost anyone else. The same enterprising spirit was shown by the prostitutes and English-speaking businessmen of Valparaiso, who brought their particular talents and the liquor pisco to San Francisco, where they became, literally, the toast of the town. Over the next decade, shiploads of Argonauts and supplies rounding the Horn made Valparaiso a regular stop, transforming it into the most important port city in the South Pacific. Likewise, Chilean agriculture was transformed, as the Chilean hacienderos planted and milled wheat in stupendous amounts. In 1853, Chile was the number one foreign supplier of California, shipping 37,370 tons of goods to the state, much of it flour.

Yet, despite the frenzy of growing and importation, the hunger of the mines was barely sated.

As with eggs, meat was almost always in short supply during the 1850’s. Cattle, sheep and pigs all brought premium prices, and enterprising herdsmen rushed to bring them into the state. Cattle and sheep were driven overland from as far away as Missouri and Texas, and enough pigs were sent from Hawai’i to San Francisco to make King Kamehameha rich.

With the arrival of the Argonauts, the great cattle herds of the californios were suddenly worth a fortune in gold. Prior to that year, the cows of Alta California were rarely sold for more than $4 a head, valued only for their tallow and hides. (In his book Two Years Before the Mast, the Harvard-dropout-turned-common-sailor, Richard Henry Dana, recounts spending the early part of 1835 off the coast of California, loading cow hides onto the brig Pilgrim for transport back to Boston.) By the end of 1849, those same cattle were going for $75 a head or more in San Francisco. The resultant cattle boom made the the dons rich enough to buy golden spurs and $1000 suits trimmed with silver, but yankee sharp dealing, out-right thievery and their own improvidence and “disaccumulationist” tendencies meant that their prosperity didn’t outlast the decade.

Despite the herculean effort to move meat to market, there was rarely enough to satisfy demand during the early years, and prices for beef, mutton and pork remained very high until at least 1855. Thus, wild game filled the gap.

Tule elk, which roamed in sizable herds throughout the Central Valley and coastal zones, were hunted relentlessly, nearly to extinction. By 1874, a single breeding pair remained, discovered in the tules reeds around Buena Vista, one of the now disappeared lakes in the southern San Joaquin Valley. Twenty-five years earlier, on the eve of the Gold Rush, there had been an estimated 500,000 tule elk; a single generation of hungry miners had destroyed the species.

Similarly, the pronghorn antelope were eradicated completely in California except in the scrubland fringe of the Great Basin in the northeastern corner of the state. White tail deer, mule deer, and mountain sheep also suffered depredations, as did anything else that flew, swam or crawled upon the surface of the earth. As a result, miners enjoyed an enormous variety of meat, not just venison, goat and elk, but everything from beaver to badger was consumed with whatever spices, side dishes and condiments happened to be at hand, usually salt, pepper and beans.

One particular favorite of the miners was grizzly bear, the former apex predator of the Sierra Nevada. A few foolhardy market hunters specialized in grizzly, staking out a fresh deer or mountain goat carcass and laying in wait for Old Ephraim to show up, at which point he would be dispatched with several shots from a newly-invented Sharp’s breechloading rifle. (Foolhardy with a breechloader, grizzly hunting would have been suicide with a muzzleloader, as one shot rarely did the job.)

Bears were valuable everywhere, even before the Gold Rush, for meat, hides and bear grease, which reportedly makes the best pie crusts. In the mining camps of California, grizzlies brought excellent prices, and the cubs, roasted whole, were judged most toothsome of all, “delicious — fat and tender”. Depending on how hungry the camp was, a fresh carcass could fetch anything from fifty cents to two dollars a pound at open auction. In 1849, in El Dorado, a 1,100 pound grizzly was sold for $1.25 a pound, netting the hunter $1,300.

In 19th century America, it wasn’t just miners who were eating bear. Cooking and consuming wild game was a sort of American pastime. The menu collector, Henry Voigt has a good post at his blog The American Menu about the much-celebrated annual game dinner at the Grand Pacific Hotel in Chicago, which featured…

…every conceivable species of game, there were dishes like ham of black bear, leg of elk, loin of moose, and buffalo tongue. Small forest animals appeared on the menu as broiled rabbit and ragout of squirrel à la Francaise. Dozens of roasted fowl were at hand, including Blue-billed Widgeons, Red-winged Starlings, and “Sand Peeps,” which could have been any one of the tiny sandpipers that once flitted along in large numbers on the North American beaches.

Mr. Voigt’s characterization of “every conceivable species of game” would have been laughed at by the half-starved miners of the Sierra Nevada, who more or less happily ate (in extremis) dogs, mules, crows, cougars, possums, ring-tail cats, and luckless skunks.

One thing, however, leaps out at you, and that is the variety of birds on 19th century restaurant menus. In fact, game birds — brought in by market hunters — were a staple in most American dining establishments right up until the turn of the century, in some cases until the middle decades of the 20th. For the miners of the Gold Rush, game birds were another source of much-needed protein. California, once so soggy in winter, is a major stop for all manner of waterfowl flying south and back again along the Pacific Flyway. In the second half of the 19th century, the lakes and seasonal pools in the central and coastal valleys were filled with what seemed like an inexhaustible supply of birds, and industrious hunters brought hundreds of them to market each week. The market-hunter, Edward Alders records taking 23,367 birds over a four-year period in the first decade of the 20th century, after most of the great flocks had gone into decline and just before California passed it’s first hunting regulations.

Aside from the horrifying numbers, the sheer variety of birds killed and consumed is astonishing. For example, sand pipers, plovers, sparrows, robins and tiny song birds all met their fate on the dining tables of California. The bigger birds were also not spared: at Christmas, sandhill cranes were sold in San Francisco as a substitute for the traditional turkey, at $16 to $20 each, and wagonloads of swans were sold for the same purpose in San Joaquin Valley towns.

Long after the Gold Rush ended, market hunters continued to kill birds in horrifying numbers. Quail hunters, not content to shoot them one and two and a time with a shotgun, resorted to nets that snared dozens at a single fall. In 1881 and 1882, an estimated 32,000 dozen were shipped from southern California to San Francisco, where they fetched $1.50 to $2.25 a dozen, below the Gold Rush prices, but still a decent living for a skilled hunter.

Quail and songbirds might be tasty, but waterfowl were always the greatest prize, and market hunters went after them with a singleminded dedication and inventiveness. I’ve not come across any accounts of punt guns (those massive boat-mounted shotguns) being used in California, but guns with four or six barrels welded together, and fired at once from a single trigger, were not uncommon. And California market hunters also pioneered a technique called “steer-hunting”, using a tame steer or bull as a mobile hunting blind, sneaking up on flocks of birds behind bovine cover and then leaping out and opening fire.

Commercial hunters continued to blast away at ducks and geese into the 1940s when the state legislature and courts finally got serious about punishing poachers, handing out substantial sentences and fines. (I am certain my late Uncle Bill, who spent 40 years as a ranger in the Mendocino National Forest, knew a few of these old timers.) There were many reasons market hunting continued as long as it did, mainly, of course, because there was an active black market for ducks and geese and restaurants continued to purchase them long after the sale of game was outlawed in California. Farmers were also complicit in the trade because they allowed market hunters access to their fields.

The six counties immediately north of Sacramento contain some of the best rice growing land in the world. They are also directly along the Pacific Flyway. The wetlands in these counties were converted to rice starting in the late 19th century, but waterfowl continued to land in the same places they had before. And, of course, ducks and geese love rice, so entire mature crops were eaten in a matter of hours, which is why farmers were happy to allow hunters onto their land. (In 1919, barnstorming pilots, the predecessors of crop-dusters, were hired to scare ducks and geese from rice fields, some even used surplus grenades.) Rice farmers have since adjusted their planting schedule, and now tout their heavily managed land, which is flooded in the fall, as “equivalent wetland“, suitable for waterfowl stopovers.

And this, the draining of wetlands for farming, brings us full circle back to the disappearance of Tulare Lake.

The Tulare Basin was incredibly rich in wildlife. Not just waterfowl, of which there were millions upon millions stopping by each year, hundreds of thousands of which wintered on Tulare Lake, but also fish and mollusks. Prior to the rerouting of the rivers, thousands of pounds of fish – sturgeon, lake trout, perch, catfish and other species — were shipped by rail from Hanford (today a dusty valley town) to Sacramento and San Francisco. In fact, one of the things that inspired this post was discovering that in a three month period in 1888, 73,000 pounds of fish were sold by commercial fishermen on Tulare Lake. Turtles were also caught and shipped live in gunny sacks to California restaurants, where they were served as terrapin soup, a staple of 19th century American fine dining.

Tulare Lake didn’t provide just fish and turtles, there were sea mammals there, 300 miles upstream from San Francisco Bay. Spanish expeditions in the early 19th century reported that the Yokut caught sea otters and seals from Tulare Lake. As proof of this, in 2004, a California sea lion, who had swam across San Francisco Bay and up the Delta, crawled out of a irrigation canal along Henry Miller Road, just north of Los Banos, and sunned himself on a CHP patrol car.

For those of us interested in the fate of the tule elks and sea lions of the Tulare, the name Henry Miller of Los Banos holds a special significance. In fact, it’s a name that ties up all of our loose threads.

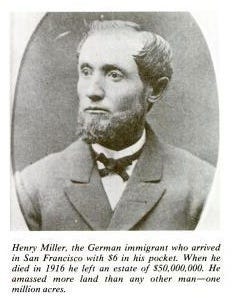

Tulare Lake was drained at the behest of a pair of German butchers who arrived in the Gold Rush and went into the cattle business in a big way: Henry Miller and Charles Lux.

The story of the Miller & Lux Corporation is one of audacity and high ambition of the sort that late-19th century America specialized in, and it’s well told by UC Irvine’s David Igler in his book Industrial Cowboys: Miller & Lux and the Transformation of the Far West, 1850, 1920. (There’s also a good recounting of Miller’s life at a site maintained by the German Historical Institute.)

Miller arrived in San Francisco in 1850 with six dollars in his pocket and promptly went to work as a butcher at $2 a day. By the time he joined forces with Charles Lux, eight year later, Miller was one of the biggest butchers in the city, and thirty years after that, in 1887, when Lux died, the pair owned nearly 1.25 million acres of land in California, Oregon and Nevada, on which grazed a million head of cattle. So great were Miller & Lux holdings that Miller said that he could ride from Oregon to Mexico sleeping every night on his own land.

Lux managed the money and politics in San Francisco, while Miller spent weeks in the saddle, managing cowboys and workers, buying cattle herds and acquiring land. Miller was foresighted enough to prefer land along creeks and rivers, land that allowed the partners to control most of the water that drained into the Tulare Basin. Starting in 1871, Miller & Lux spent tens of millions in today’s money on reclamation and irrigation projects, building hundreds of miles of canals that converted large parts of the San Joaquin Valley into first rate cattle and dairy land.

And that’s what happened to Tulare Lake. Miller & Lux drained it. Not on purpose, but by rerouting its waters to grow hay to feed cattle, in a place where the average rainfall is less than ten inches per year. And it was done with the approval of other ranchers, farmers and the state legislature, and has been celebrated by Americans as a triumph of civilization.

On August 14th, 1898, the San Francisco Call was able to declare the following:

Tulare Lake has passed out of existence. Where once there was a body of water in Central Southern California over a thousand square miles in area, now there is only a barren desert of mud, drying and cracking in the heat of the desert sunshine.

It wasn’t exactly true. Tulare Lake came back again, greatly reduced, during the rainy season of 1901, disappearing the next year. It continued to periodically make its presence known in the wet years, when floods refilled the lowest parts of the lake bed. Sometimes the water would last for a couple of years before it evaporated. The last time this happened was in 1998, when around 50,000 acres of J.G. Boswell‘s government-subsidized cotton fields were flooded for two years. (When you’re standing at the In-n-Out, looking eastward, it’s J.G. Boswell land you’re seeing.)

As of 2015, Tulare Lake is unlikely to appear again anytime soon, as the southern San Joaquin water management system is probably the most highly developed irrigation and drainage network in the world, thought capable of handling all but the most catastrophic rainy seasons. (John Austin’s Floods and Droughts in the Tulare Basin has a comprehensive account of the hydrologic history of the Tulare Basin.)

One final note: In 1874, when what was thought to be the last breeding pair of tule elk were discovered in the reeds around Buena Vista Lake, it was on Miller & Lux land. And it was Henry Miller who gave orders to save the tule elks.

Over the next two decades, a few more individual elk were found on Miller & Lux land. In every case, Miller had the animals captured and moved into a small herd in Northern California. By the time Miller died in 1916, there were several hundred animals in his herds scattered throughout the state. Today, there are nearly 4,000 tule elk living in 22 herds in California, all saved by the man who drained Tulare Lake.

N.B. This was something I wrote a couple years ago and published at my old website. I had a busy weekend and not enough time to write. I’ll be back on Thursday with something brand new. See you then!

Great post! It's impossible to know all that we lost in California. Tule Elk are coming back slowly though, but they're here to stay again. There's a good size herd by San Luis Reservoir that I love to see them at.

Are you sure about your claim about Whitetail deer? As far as I've read, Whitetails have never been native to CA. Perhaps you meant Blacktail?

Wonderful piece about CA history. My father's side of the family came to CA for the gold rush and were granted the Paso Robles land grant (which they lost entirely by 1900). I've often wondered what they ate. Obviously not fabulous Santa Maria bbq. The climate thing is interesting. There's a story about a sundowner sweeping through Goleta (where I grew up and we now live) that was so hot birds fell dead out of the skies and cattle toppled over. Some say it's myth. In my opinion, if CA could get rid of the climate change activist billionaires the weather would be better.