A History of Chicken and Waffles, Part 2

The Most Complete Expression of Southern Culinary Skill

In Part I—published last week—I noted that chicken and waffles is historically three different dishes: creamed chicken and waffles, broiled chicken and waffles, and fried chicken and waffles, each of which had its moment in the sun.

Of the three, it’s probably broiled chicken and waffles that had the greatest fame in the mid-19th century. The most celebrated purveyor of broiled chicken and waffles was Warriner’s Tavern in Springfield, Massachusetts, an old fashioned coaching inn run by Jeremy “Uncle Jerry” Warriner and his wife Phoebe.

Aside from the fact that people were writing poetry about the tastiness of Aunt Phoebe’s chicken and waffles for decades after her death, what was most interesting was that Springfield, Massachusetts, wasn’t below the Mason-Dixon line. Remember, chicken and waffles are supposed to be the “most complete expression of Southern culinary skill”, not a dish that made “modest fortunes” in the land of the bean and the cod. So, what was the secret ingredient in Aunt Phoebe’s broiled chicken and waffles that made them so delicious? In two words: runaway slaves.

If you remember your U.S. History I, Western Massachusetts was a hotbed of abolitionism, and Springfield was ground zero, a place where John Brown sharpened his madness before heading out to make Kansas bleed. The Warriners were staunch abolitionists and their tavern a major stop on the Underground Railroad. We know that Aunt Phoebe’s kitchen was staffed with African-American women who in a previous life had probably been plantation cooks, or at least trained by plantation cooks. As I showed you in Part I, or rather as David S. Shields showed you in his book Southern Provisons: The Creation and Revival of a Cuisine, plantation cooks were likely the best chefs in America, rivaled only by a few French chefs in New Orleans and New York.

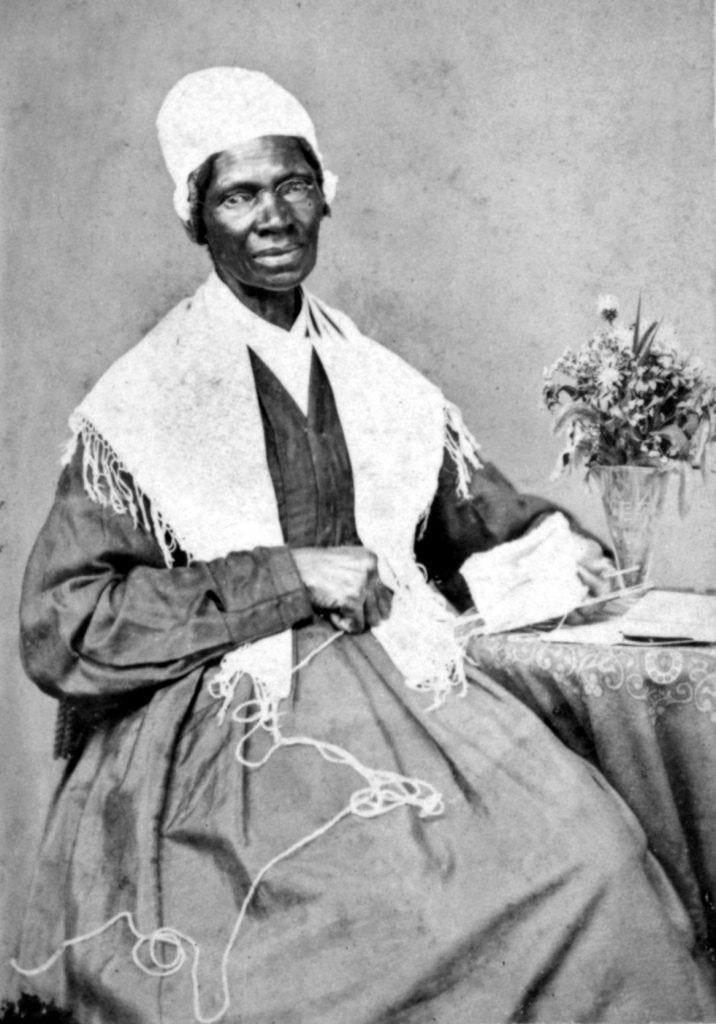

We also know the names of at least two of the African-American cooks at Uncle Jerry’s: Mary Sly and Emily, the latter a virtuoso pastry chef. Emily’s full identity has eluded me. Mary Sly, however, is better known. In 1855, she was one of a number of fugitives who were living in Florence, 20 miles north of Springfield, a village famous for it’s liberty-minded residents such as Sojourner Truth.

Sly, said to have been born in either New Orleans or Natchez, worked for a time at the tavern run by Jeremy Warriner in Springfield; she escaped from her owner, a “Col. Trask,” and it may be at that time that she came to Florence, where she was listed in the 1855 state census.

This is where I ended Part I, noting that the man who had once owned Mary Sly was a congregant at the same church as Uncle Jerry and Aunt Phoebe, the First Congregational Church in Springfield, where the Reverend Samuel Osgood, an ardent abolitionist, presided.

Colonel Israel E. Trask was one of those ambitious, energetic Massachusetts Yankees that turned up everywhere in the 19th century, from Santa Barbara to Shanghai, seizing the main chance with both hands and not letting go. The son of a Revolutionary War veteran and prominent surgeon, young Trask had been educated at Yale, trained as a lawyer, and briefly served in the Army. He was on the edge of heading off to France in 1801 when Alexander Hamilton suggested he go to Mississippi instead, and he did. Once there, he fell in with the right crowd, married a planter’s daughter and acquired two huge plantations, one near Natchez and the other closer to New Orleans.

In 1812, after making a fortune growing cotton, Trask turned the management of his plantations over to his brother and headed back to Massachusetts, where, in an early example of vertical integration, he opened a cotton mill. Yes, Israel E. Trask was both a southern planter and a Yankee industrialist, a career trajectory that was not as uncommon as you might imagine.

This is the place where I point out something you might not have thought about. Springfield was a hotbed of abolition because Massachusetts fortunes were being made on the backs of enslaved people, directly in the case of men like Col. Trask, and indirectly through the ownership of cotton mills. In fact, the Deep South—Mississippi, Alabama and Louisiana—was lousy with transplanted New Englanders, men like Edwin T. Merrick, another Springfield-lawyer-turned-Louisiana-planter, who was the Chief Justice of the Louisiana Supreme Court. Rather than surrender the court to the hated Yankees, when Union General Benjamin “Beast” Butler (another Massachusetts lawyer) entered New Orleans, Merrick took the court into exile in Confederate-held Shreveport and kept it operating until the end of the war.

Because of the close familial and commercial ties between Southern cotton planters and Massachusetts textile barons, and because of the unbearable heat, malaria and yellow fever in the summer, many planters, like Col. Trask, spent their winters in the South and summers in New England. And when planters like Col. Trask traveled north, they brought their lady’s maids, valets and cooks with them, which meant that the citizens of New England mill towns had more direct contact with planters and enslaved people than most other Northerners. Springfield wasn’t technically a mill town—it specialized in precision manufacturing—but it was a major transportation hub, the first stop in Massachusetts for the steamboats that went up the Connecticut River, with railroads leading outward in all directions by 1845.

State law and friendly judges meant that Massachusetts was effectively a free state; slaves who traveled with their owners could “self emancipate” as soon as they stepped off the boat. In the case of Col. Trask, self-emancipation seemed to happen more than once. I’ve not had a chance to examine the Israel E. Trask collection at Amherst College (Trask was one of the founders of the college) or the duplicates of the collection at Harvard, so I do not know if there is more to be learned about Mary Sly and whether she ran off or self emancipated. I do know, however, that Uncle Jerry’s was a place where self-emanicpation was encouraged. In fact, one of the most famous cases of recanted self-emanicipation started in the dining room at Warriner’s tavern in August of 1845.

One W. B. Hodgson, a slaveholder from Savannah (Geo.) with his lady and slave by the name of Catherine Linda, came into Springfield about three weeks since and stopped at Warriner’s U.S. Hotel. At the same time a friend from New-Bedford, a fugitive slave, in company with another family, stopped at the same place. He fell in with Catherine Linda, and soon found that she was a slave travelling with her master. She repudiated slavery, and expressed a desire to be free.

That short snippet is taken from radical abolitionist Erasmus Darwin Hudson’s account of the incident as recorded the abolitionist newspaper, The Liberator.

Unfortunately, when Catherine Linda was given her moment before a judge who had the power to confirm her freedom, she recanted—probably because her entire family was in Georgia—and returned to the South with her master and mistress. (Oddly, Hodgson, a scholar and former American diplomat, was a gifted linguist who was familiar with most of the African languages common among slaves, including Mandigo, Ebo, Gullah and Fula.)

So, by the 1840’s, broiled chicken and waffles had been spread to the north by runaway or freed slaves, well-trained cooks like Mary Sly, who occupied key positions in celebrated eating houses, such Uncle Jerry’s Tavern. But what about fried chicken and waffles?

As I noted in Part One, outside of the South, young chicken was an unusual and costly treat. Below the Mason-Dixon, however, it was a common staple on breakfast tables, fried or broiled, and served with a variety of breads and biscuits, including waffles. The reason chicken was more abundant in the South was that chickens long held a special place in Southern slave society, because they were the one type of livestock enslaved people were usually allowed to own for themselves. Andrew Lawler’s 2014 book, Why Did the Chicken Cross the World, gives a good accounting of the southern chicken economy, of dunghill fowls as the key commodity in a lively commerce of eating, trading and selling carried out by enslaved people and freed blacks.

In what likely was a typical exchange, Thomas Jefferson in 1775 bought three chickens for two silver Spanish bits from two of his female slaves who worked at the Shadwell plantation. In the early 1800s, when he was away serving as president of the United States, Jefferson’s granddaughter Ann Cary Randolph recorded each purchase made while she helped manage the estate in his absence. Chickens and eggs were the item most commonly sold by slaves to the white household.

Enslaved people also grew a large range of vegetables in their garden allotments and sold the produce to their masters and others, although nothing was ever as lucrative as poultry. Here’s Andrew Lawler again.

In 1728, a white owner named Elias Ball paid one pound and fifteen shillings for eighteen chickens to his slave Abraham. A savvy businessman, Abraham then threw in one chicken for free. Planters bought up to seventy birds at a time from their human chattel.

Chickens were so lucrative that industrious slaves might, in rare cases, even be able to buy their own freedom with the earnings from their birds. Lawler wryly notes that, slaves often “had a strong economic incentive to encourage their masters to eat more chicken.”

Which brings us, at long last, to the topic of fried chicken and waffles. If you want to know about the history of Southern fried chicken, go read John T. Edge’s book, Fried Chicken: An American Story, and if you want to know, in a general way, about Southern fried chicken and waffles, this passage from Adrian Miller’s book Soul Food: The Surprising Story of an American Cuisine is a good summary of the basic truth.

By the early 1800s, a “Virginia Breakfast,” featuring a combination of fried or baked meats with any sort of hot quick bread, was the gold standard of plantation hospitality. At these meals, fried chicken was a regular star, just as likely to be paired with a biscuit, cornbread, pancakes, or rolls as a it was with waffles. It was enslaved African American cooks who made the Virginia Breakfast possible. After Emancipation, these same cooks frequently made chicken and waffles for social events in the black community, and worked as professional cooks in elite hotels, resorts, and restaurants patronized by wealthy whites. Through their culinary talent, African American cooks effectively mainstreamed chicken and waffles by the early 1900s.

While Adrian Miller’s thesis about the genesis of chicken and waffles is solid, it’s lacking, as most of these accounts are, in specific details, probably because it’s impossible to go back much before the Civil War and find mentions that emphasize the unity of the dish.

What I mean is, accounts of plantation breakfasts might put fried chicken and waffles together on the breakfast table, but they’re usually accompanied by a host of other tasty things—from beaten biscuits to baked meats. Fried chicken and waffles is not a dish because fried chicken and waffles are not yet “a thing”, singular.

Having said all that, my best guess is that fried chicken and waffles achieves thinghood in parts of the South just before the civil war, and then takes off in the North in the mid 1870s, achieving nationwide apotheosis by the turn of the 20th century. Here are the opening lines from an antebellum short story, “Miss Polly Peablossom’s Wedding”, published in 1842 by John B. Lamar, a Georgia planter who dabbled in regional humor and died on a Maryland battlefield in 1862.

“My stars! that parson is a powerful slow a-cominng! I reckon he wa’nt so tedious in gitting to his own wedding as he is coming here,” said one of the bridesmaids of Miss Polly Peablossom, as she bit her lips to make them rosy, and peeped into a small looking-glass for the twentieth time.

“He preaches enough about the shortness of a lifetime,” remarked another pouting Miss, “and how we ought to improve our opportunities, not to be creeping along like a snail, when a whole wedding party is waiting for him, and the waffles are getting cold and the chickens are burning to a crisp”

We can thus establish that chicken and waffles were a dish suitable for serving at country weddings in antebellum Georgia, probably cooked, of course, by the slave women who ably commanded the plantation kitchens.

The big nationwide boom in fried chicken and waffles began in the 1870s, paralleling the rise of a national railroad network that eased the burdens of long-distance travel.

Before the Civil War, travel to the South largely meant taking a steamer down the Atlantic coast to Charleston or Savannah, or down the Ohio River to the Cumberland or Mississippi, and thence inland from one of the ports, sometime by local rail, but mostly by coach. In other words, it was slow and arduous, and not something to be undertaken lightly.

As long distance travel got easier after the Civil War, working in what today is called the “hospitality industry” was one of the fastest way for freed slaves and their descendants to earn a respectable living. George Pullman, of the Pullman car, exclusively hired ex-slaves as sleeping car attendants and porters, men who earned middle class wages by focusing on superior customer service. At rail stations throughout the South, many African American women also earned a decent living by selling prepared food to train passengers. Amos Gottschall, a patent medicine salesman who roamed the continent after the Civil War, was especially impressed with “waiter-carriers”, women who walked great distances with platters of food balanced on their heads.

About the first words a traveler hears as the cars stop at a station in the South, are these: “Here’s yer nice, tender chicken, hot coffee and waffles!” and the next moment, a good-natured old Sambo or Aunt Hannah comes to the car-window, carrying on his or her head a large waiter containing nicely fried chicken and waffles, as well as a shining coffee-pot full of steaming Java.

The small town of Gordonsville, Virginia, located at an intersection that connected Richmond with the Shenandoah Valley, gained fame for the quality of its fried chicken, sold trackside to passengers by an army of waiter-carriers.

Resort hotels throughout the country hired freed slaves and their children to staff their kitchens, and canny promoters and hoteliers began to advertise Southern fried chicken dinners as a significant attraction.

By the turn of the century, the cult of fried chicken and waffles had spread to distant parts of country, to places like New York City, Western Massachusetts, and the Hale’iwa Hotel in Hawaii. (The later founded and run by Benjamin Dillingham, another Massachusetts Yankee adventurer who got rich on native land and chutzpah.) By 1920 there were several Southern restaurants, “tea rooms”, in New York City, such as the Yellow Aster, the Adelaide, the Pirouette and the Southern Tea Room, that regularly offered fried chicken and waffle dinners.

Fried chicken, with or without waffles, became so important that Jessup Whitehead, the Mark Twain of 19th century cookbook authors, considered it the essential factor in whether or not a resort succeed.

It is quite appalling to think how many men of means and brains rush into the business of keeping summer resort hotels who are and remain utterly ignorant of the fact that the first principle of resort keeping is

PLENTY OF FRIED CHICKEN

and not knowing this, they fail and the next summer the “unfortunate”, the chickenless hotel remains closed. True, your guests love other things, too. They love music and fried chicken; electric lights and bells and fried chicken; telegraph and post office in the house, and fried chicken; great elevations and pine woods and fried chicken; fine drives, all sorts of amusements and all other modern conveniences and fried chicken; but as nobody expects to get all the good things in this world at once if any of the preliminary inducements should be lacking, still if fried chicken remains, the guests will stay, too.

At the same time fried chicken and waffles were conquering the hotel business, American housewives began to up their cooking game. Post-war industrialization in the North caused wages to rise to the point that middle class families were unable to hire reliable servants at reasonable rates. One response was to import young women from Ireland, who as I showed in my piece, “The Curse of an Irish Cook”, were woefully untrained in the art of American cookery.

Another, more common response, was for young women to get the training in cooking their mothers—who had benefited from cheap labor—did not provide. Cookbooks were thus published in great number, ladies magazines proliferated, and cooking schools sprang up across the country.

One of the first celebrity chefs to emerges in this era was Maria Parola, yet another Massachusetts native, who spent five years in Jacksonville, Florida, as a school teacher, before returning to Boston and opening Miss Parola’s School of Cooking in 1877. Her success as a lecturer, writer of cookbooks and teacher of cooking inspired many rivals, including the more famous Mary J. Lincoln and Fannie Farmer, both also based in Boston. It was Parola, however, who probably did the most to inspire Northern cooks to attempt Southern dishes. This excerpt from the St. Paul Globe, May 3, 1886, shows the esteem in which she held southern cookery.

Miss Parola, the famous exponent of common sense cookery has been making tour of the South. As a result of her investigations she declares that the women of the South are better cooks than their Northern sisters. If the lady has allowed her judgement to become prejudiced under the seductive influence of the fried chicken and waffles which form the most complete expression of Southern culinary skill, she is perhaps excusable for her evidently biased statement.

So, there you are. By 1886, fried chicken and waffles was considered, rightly or wrongly, “the most complete expression of Southern culinary skill.” The thinghood of fried chicken and waffles had finally been achieved.

Note that praise for the dish was being given to Southern housewives, not to plantation cooks, for the obvious reason that this was a generation after the Emancipation Proclamation, a generation during which the impoverished South, unlike the more prosperous North, had not experienced an economic boom. Miss Parola’s assessment that Southern women were better cooks than Northern women was likely because Southern women had fewer servants after the war and more hands-on experience at the art of cooking. Or, more plainly stated, with talented slave-cooks freed, middle class Southern women had to do their own cooking, and as a result became good at it.

Fried chicken and waffles also gained in popularity among home cooks because of improved technology. Baking powder, newfangled patent waffle irons and gas stoves were making it easier for housewives to prepare waffles at home.

Originally, the old-fashioned yeast batters had to be prepared well in advance of cooking, and long-handled waffle irons wielded in open fireplaces made the actual cooking a difficult and sometimes dangerous task, which was why waffles were considered such as special dish, why they could only be made by people with lengthy training in the art of wafflery and why plantation breakfasts, of which they were a prominent part, were so often cited as the peak of luxury.

Here, I probably should address the Aunt Jemima problem because it ties together so much of what we’ve been talking about: post-Civil War industrialization, housewives cooking breakfast, the spread of Southern food culture and the role of African-American women in it. But, I’m not going to. It’s too wickedly complex to treat in a fluffy piece on chicken and waffles. Instead, go read Toni Tipton-Martin’s book The Jemima Code. It’s worth your while because Tipton-Martin reminds us that there are two sides to the stereotype of the black mammy. On the one side, the offensive racial caricature that reduces African-American women to perpetual happy servitude while reasserting white dominance; on the other, the genuine feelings of warmth that many white Southerners felt for the black women who raised and fed them. The caricature is racially offensive, but the positive emotions were genuine, and both things exist in the same space at the same time.

The letters of Israel Trask, the Massachusetts mill owner/Mississippi planter, catch something of what the novelist Kathryn Stockett refers to as, “the dichotomy of love and disdain living side-by-side.”

Trask’s letters home speak in familiar terms about the individual slaves, their health, and living conditions. He wrote of slaves’ frequent inquiries about his wife and children—the “Missis” and “Massa Wm. and Ed”—and of sharing food with the “young negroes.” James Trask, a brother who managed the family’s extensive Mississippi holdings, spoke of “our Black family.” The labor force at the Massachusetts mills is never discussed in such personal terms.

As I tell my students, slavery is inhumane but human. It’s an ancient evil system devised by humans in an era before industrialization. But because human emotions are complex and irreducible, familial affection can exist between oppressor and oppressed, which is why slavery is so horrifying and why it corrupts so thoroughly. For the past 130 years, Aunt Jemima has been the echo of that fraught familial connection, ripped from its terrible context and turned into commercial success by advertisers and industrialists.

Let’s end this story where I started Part One, with an American president feasting on chicken and waffles. If you remember, I began by referencing the 1867 meeting of future president William McKinnley and his future bride Ida Mae Sexton, which happened at “a chicken and waffle supper, for which the old hotel at the lake was famous throughout several counties.” The lake in question was Meyer’s Lake, three miles west of downtown Canton, Ohio. Meanwhile six miles west of Meyer’s Lake was the city of Massillon, Ohio, a hive of Quakerism and one of the most important cities on the Underground Railroad, and a place where many escaped and freed slaves settled, both before and after the war. And, you can see where this is heading… who it is I believe probably cooked the chicken and waffles at Meyers Lake. Needless to say, there’s more work to be done on the hidden history of African-American cooks in post-Civil War America.

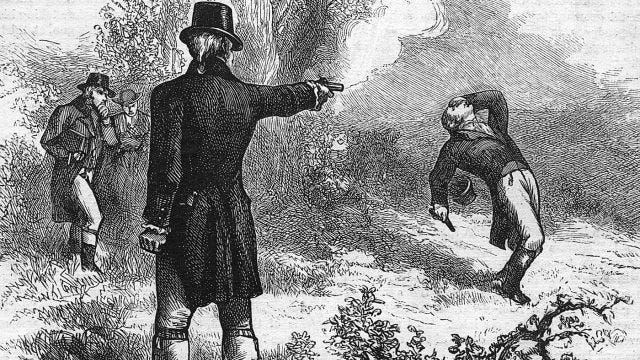

And, now, finally, the denouement. What may be the earliest reference to fried chicken and waffles being eaten together is found in the biography of another American president, History of Andrew Jackson: Pioneer, Patriot, Soldier, Politician, President, written by Augustus C. Buell and published in 1904.

Buell records the following..

They arrived late — about 8 p.m. — at the tavern. The General ate a hearty supper of fried chicken, waffles and sweet potatoes, with coffee. After supper he lounged about on the piazza smoking his corn-cob pipe and chatting with the citizens until 10 o’clock. Then he went to bed, was asleep in ten minutes, and had to be shaken pretty rudely to wake him up at five in the morning. His breakfast was light—only one hot biscuit, two eggs and one cup of coffee.

We know the exact date of this supposed meal, Thursday, May 29, 1806, because the next morning, Friday, May 30, 1806, Andrew Jackson killed fellow Tennessee planter and rival horse breeder, Charles Dickenson, in a duel at Harrison’s Mills near Adairville, Kentucky. The night before the duel, Jackson had stayed at David Miller’s Tavern, located on the Red River, just across the Tennessee-Kentucky state line. Dueling was forbidden in Tennessee, but not Kentucky, hence the need for overnight accommodations. If Buell’s account of Old Hickory’s dinner is correct, it’s evidence of someone eating fried chicken and waffles at the very beginning of the 19th century.

Unfortunately, it’s almost certainly a fabrication. None of the 19th century biographers of Jackson mention dinner at Miller’s Tavern, and those that that do, like James Parton, are content to say that Jackson “ate heartily,” without naming the dishes.

Far worse, Augustus Caesar Buell, who had written several popular biographies of major American figures, was revealed after his death to have been a fabulist of some ability and industry. He long dined out on having been a lieutenant colonel of a New York regiment during the Civil War, but had never made it past corporal. His best-selling biography of Revolutionary war hero, John Paul Jones, was so filled with lies that Harvard history-professor-turned-admiral, Samuel Eliot Morison, devoted an entire appendix to debunking them. So Buell’s account of a dinner of chicken and waffles, sweet potatoes and coffee, is a probably a lie.

Yet, I think it’s telling that Buell, a native New Yorker who barely made it to the South, chose chicken and waffles as Jackson’s pre-duel meal. Telling, because by 1900, chicken and waffles had jumped the Mason-Dixon Line and had become a “thing”, a very big thing, in the rest of the United States. In fact, it had become the dish most closely identified with Southern cuisine, avidly desired by millions and widely acknowledged by most as the “complete expression of Southern culinary skill”.

Thanks for your attention and support. I’ll be back soon with something new. In the meantime, please follow me on Twitter and like An Eccentric Culinary History on Facebook. Cheers!

Are you okay? Are you still writing this blog?