A History of Chicken and Waffles, Part 1

The Most Complete Expression of Southern Culinary Skill

Chicken and Waffles are bacon and eggs: not so much a single dish as an inspired combination of two different things forever joined in glorious union.

As with bacon and eggs, however, finding a single point or origin for chicken and waffles is a fool’s errand, a silly task made triply difficult by the fact that, often enough, historical sources could be referring to any of three different iterations: Southern fried chicken and waffles, the soul food staple turned hipster fetish; stewed chicken and waffles, a delicacy of long standing in Pennsylvania Dutch country; and broiled chicken and waffles, a 19th century preparation that sent diners into flights of ecstasy.

Three version makes for a difficult historical problem. So, for example, this newspaper clipping from The San Francisco Call, May 12th, 1901, doesn’t give us enough evidence to say which of three varieties was served.

The major’s first impression of Miss Saxton was gained at a chicken and waffle supper, for which the old hotel at the lake was famous throughout several counties. He was particularly delighted with the fact that she ate chicken and waffles as if she had a healthy appetite, instead of affecting the live-on-air style that was the raging fad with young ladies at that particular period. From that moment on his admiration grew and she on her part had a marked admiration for the brave and handsome young major.

This charming story of the dashing young Union veteran and the maiden with the appetite describes the 1867, Canton, Ohio, meeting of future President William McKinnley and his wife-to-be Miss Ida Saxton.

To be clear, I think it’s fried chicken that Miss Saxton may or may not have been gobbling, but I can’t be certain. What I can say, however, is that in the 19th century and early 20th century chicken and waffles, all three kinds, were celebratory food; a special treat not often (if ever) prepared at home, unless your home was a Hudson Valley Dutch farmstead or a Southern plantation.

Before baking powder and cast-iron stoves, good waffles were hellaciously hard to make. The best and lightest waffles were made to rise with yeast and cooked over an open fire in long-handled waffle irons. Making the dough was a laborious process, usually started the night before the breakfast service, or early in the day for an evening “waffle frolic“. The heavy irons were not just expensive speciality items, they were difficult to handle without burning yourself, and getting them to produce a perfect golden-brown waffle was strictly a matter of experience.

The heavy irons had to be propped just so before the fire and turned frequently and, obviously, they had to be watched closely. And according to Peter Rose, a single waffle takes six to eight minutes to bake in a fireplace iron, which means that producing enough waffles to fill a serving dish would take a half hour or more. In early nineteenth-century America, waffles were, in fact, a distinctly upper-class food, and while some privileged women did bake (or have their help bake) them at breakfast for family, they were mostly company fare.

It’s the difficulty of making waffles that is one of the keys to understanding the place of chicken and waffles as festive food in 19th century America. The other is that chickens were not as commonly eaten as they are today, mainly because they were expensive to produce or purchase. I discussed the reasons for this in my long piece on poultry farming in 19th century California. Essentially, chickens were more valued for their eggs than their meat, while game birds (ducks, geese and almost anything that flew) could be purchased more cheaply than chicken from market gunners or game stalls in city markets. Until the migratory flocks of the Chesapeake were depleted, starting in the 1870s, chicken could not compete economically on a grand scale.

Thus, with one regional exception, the South, if chickens were eaten at home it was usually at one of two life stages: broiled as spring chickens, the young males culled from the flock in late spring, or stewed as old hens, after they’d ceased to lay. The thrifty Germans and Dutch (the people of the waffle) took these old birds and slowly simmered them, pulling or shreding the tenderized meat and finishing it in a cream or butter sauce, a preparation that gives us the basis of the Pennsylvania Dutch chicken and waffles.

William Woy Weaver gives a good account of the history of this style of chicken and waffles in the Fall, 2020, issue of Pennsylvania Heritage.

I like Weaver’s version because it acknowledges that the association of this dish with Pennsylvania Dutch and Amish tables is a fairly recent thing, and has more to do with tourism than long tradition. This is made clear with a description of the festive catfish-and-waffle dinners served in taverns and hotels along the Schuylkill River near Philadelphia, a tradition that began in 1813 with the opening of Mrs. Watkins’ Falls of the Schuylkill Hotel and ended six or seven decades later when the river became too polluted to support bottom feeders. The important thing to know is that catfish and waffles (not usually together, but as part of a multi-course meal) were what 19th century, working and middle-class Philadelphians thought of as fine dining, a regional version of a proto-Red Lobster.

Here’s a stanza from Charles Karsner Mills, 1876, The Schuylkill: A Centennial Poem that gives you the low-down.

Far-famed these inns through many a year

For hospitality and cheer

For bill-of-fare peculiar here–

Catfish, and coffee, beefsteak fine,

Broiled chicken, waffles and good wine.

Such fare Savarin sure would glad,

Or drive a monk with pleasure mad.

The white catfish along Wissahickon Creek, a Schuylkill tributary, were especially abundant and judged, “dainty and toothsome and when served with the equally famous waffles brought visions of Paradise on earth.” Even before the catfish ran out along the Schuylkill, the multi-course meal, with chicken (fried, stewed or broiled), waffles and hot coffee, was a staple of inns and hotels throughout the Mid-Atlantic and Northeast.

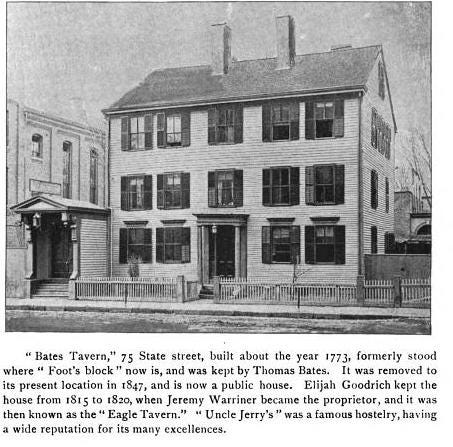

In fact, in the mid-19th century, chicken and waffles were such a draw that substantial commercial reputations and “modest fortunes” could be made on them. In Springfield, Massachusetts, the Warriner Tavern, run by “Uncle Jerry” Warriner and his wife “Aunt Phoebe” became so famous for their broiled chicken and waffles –“known and gratefully remembered in two hemispheres.”– that decades after Uncle Jerry’s death in 1859, people were still talking about his food.

In 1887, a letter appeared in the Springfield Republican from the “Baroness von Oppen”, who as a young woman named Julia Leicester, had lodged with the Warriners nearly 40 years earlier, in 1850.

Madam is aware that both Mr and Mrs Warriner have long since passed away from this life; but they had a niece named Miss Lydia Bates, and a grand niece, Miss Sarah Moses, both or either of whom the Baroness von Oppen would like to see if she went up to Springfield in October for one more look of that dear, sweet and peaceful place, where God seemed to be in the people’s homes and hearts, in the Indian summer, when the girls used to sit on the verandas and sing the old little quaint songs that nobody ever sings now. […] Mr. Akin was the manager at Mr. Warriner’s hotel renowned for broiled chicken and “waffles”.

I should note that the Baroness was not a Baroness, was not even Julia Leicester, but rather an Irish-German adventuress named Caroline Henshaw who had been living with gunmaker Samuel Colt’s brother John C. Colt when he murdered his publisher over a dispute about the 5th edition of his text on double-entry bookkeeping. Before taking up with John, Henshaw had previously been Sam Colt’s mistress (and/or wife) and had bore a child that was probably Sam’s. There’s a lot more to this tangled story, including a “marriage” to a young Prussian noble, but by 1887, the Baroness was reduced to living in Londonderry, Ireland, and sending out letters begging for money. But, despite a life filled with incident and excitement, Henshaw still remembered Aunt Phoebe’s chicken and waffles.

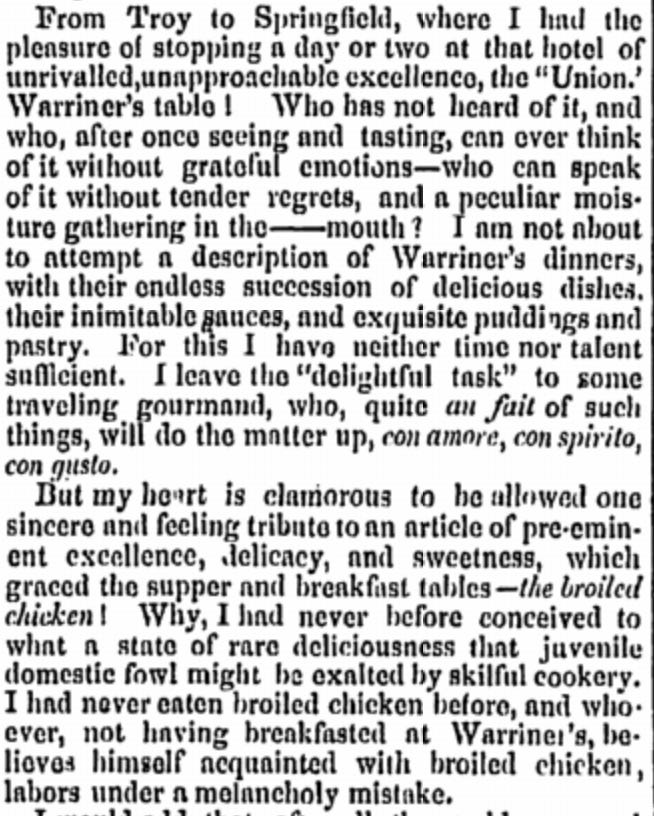

For another encomium to Aunt Phoebe’s broiled chicken, one that’s just too good to omit, here’s Grace Greenwood (a.k.a Sarah Jane Lipincott) describing the merits of dining at Uncle Jerry’s.

But my heart is clamorous to be allowed one sincere and feeling tribute to an article of pre-eminent excellence, delicacy , and sweetnes, which graced the supper and breakfast tables—the broiled chicken! Why, I had never before conceived to what a state of rare deliciousness that juvenile domestic fowl might be exalted by skillful cookery. I had never eaten broiled chicken before, and whoever, not having breakfasted at Warriner’s, believes himself acquainted with broiled chicken labors under a melancholy mistake.

Chicken for breakfast? In Massachusetts!

Notice, also, that Lippincott, who was 26 at the time of this letter, had never tasted broiled chicken before.

So, what was the secret to Aunt Phoebe’s memorable broiled chicken and waffles?

In order to answer that question I’ve got to open a whole can of very particular American worms, ones that will eventually lead us to the topic of southern fried chicken. But, first, let’s note again that, although Aunt Phoebe died in 1854 and Uncle Jerry in 1859, people really couldn’t stop talking about their food.

Here’s a mention from 1877.

The United States Hotel, afterwards rebuilt and called Warriner’s Union House, was known throughout the continent, being noted for its home comforts and fine cookery, especially the latter, in the good old days when it was done by the first-class American housewives, instead of being entrusted to “Biddy,” or anything but a good cook. Mrs. Warriner was the queen of the household, who presided in the realm of the kitchen, as well as in the parlor, and, like thousands of her countrywomen of that day, was more proud of her rule and triumphs here than ever Victoria was of the throne and scepter of Great Britain

Such fulsome praise for our hostess!

Here’s another, from 1866.

A great revolution in the conduct of a hotel was made in the administration of Warriner of Springfield, who so suffused his table with delicacies, that a week at his house was a perpetual feast—and no one ever sat at his tea table especially, and was waited on by “Emily”—but found a new chapter in the gastronomic life.

There are many more I could show you — including a poetic one from the 1950’s — but I picked these two because they demonstrate how hard it is sometimes to sort out who’s really doing the cooking. Did you catch the meaning of that bitter-tasting line in the first passage?

” …in the good old days when it was done by the first-class American housewives, instead of being entrusted to “Biddy,” or anything but a good cook.”

That’s a complaint about Irish cooks taking over the kitchens of New England. Biddy is to Bridget as Paddy is to Patrick, the catch-all nickname for an Irish worker of low status. Irish servant girls worked more cheaply than Americans, but they were not well-trained in the kitchen, not compared to the people they were replacing. No Irish peasant girl had ever seen a waffle, much less fried a chicken, planked a shad, or soused a hog’s head. Those culinary tasks were best done by “first-class American housewives,” or “a good cook”.

Aunt Phoebe was a first-class American housewife — the toothsomeness of the food and the cleanliness of the rooms proved it –but no American housewife, however first class, could have single-handedly run an antebellum commercial kitchen. In fact, given the demands of large farm families and open-hearth cooking, antebellum housewives rarely ran domestic kitchens single-handedly. They had daughters and servants to help them.

So, who were Aunt Phoebe’s helpers? Who cooked the waffles and broiled the chickens?

Here’s an important fact I’ve withheld from you: like many people in Springfield, Uncle Jerry and Aunt Phoebe were staunch abolitionists (“zealous workers” for the cause) and their tavern was a major station on the Underground Railroad. There was even a large grain bin in the storeroom where, in an emergency, half a score of runaways could be hidden from slave catchers.

In 1907, on the eve of the destruction of the old hotel building, the Springfield Homestead published the reminiscences of Julia Lee, the daughter of one of those fugitives.

The way I happened to be born there, my mother, Mrs. Mary Sly, was a cook with Uncle Jerry. She came from Natchez, Miss. up here, and mother was born in New Orleans. Father was a West India man. Uncle Jerry had all colored help, men and women. Aunt Phoebe’s (Mrs. Warriner’s) aunt used to do the cooking. A colored girl, Emily, did all the pastry. Jane Hall and I helped wait on table. I used to feel quite proud when some of those big folks would come in on the stage and when they’d sit down at the table would say, “Where’s Julia, I want Julia to wait on me.” Those folks were generous about tipping, too. They would leave money around under the plates, often 25 cents and sometimes as much as a dollar.

Among the “big folks” who stopped by Uncle Jerry’s was Senator Rufus Choate, who together with Daniel Webster (both frequent visitors to the tavern) defended Uncle Jerry in a lawsuit in the early 1840’s. This 1907 account of the eve of the trial is from Sara Moses Warriner Merrick, Uncle Jerry’s grand-niece and adopted daughter.

I remember Rufus Choate coming into the big kitchen night of the argument and saying to Aunte Phoebe: “Give me the strongest cup of tea you ever made, Mrs. Warriner, and some of Mary Sly’s” (she was an old black cook that lived her life there) “best waffles and broiled chicken, and I’ll carry it through,” and he did.

So, Aunt Phoebe’s kitchen help was her spinster niece, Lydia Bates (“Aunt Lydia”), presumably trained to be a “first-class American housewife”, and a pair of African-American women, Mary Sly, responsible for chicken and waffles, and “Emily” the pastry chef, the same one who supplied the tea table with its delights.

Except for a handful of French chefs scattered around the country, there were few chefs as well-trained as the best plantation chefs. David Shields’s remarkable book on the history of Low Country cuisine, Southern Provisions: The Creation and Revival of a Cuisine, details the extensive apprenticeship some of these chefs underwent, apprenticeships overseen in Charleston by prosperous free people of color, such as Eliza Lee. Once fully trained, these African-American chefs, both male and female, were at the top of any Southern household’s black hierarchy.

[A] plantation cook excelled through the consistency of her preparations and her economy; an urban cook for elite households excelled in the abundance of ingredients, and in her ability to maintain the latest culinary fashions and technological innovations in the kitchen. The best city practitioners were designated “complete cooks,” and their skills commanded such respect that free cooks won a regular clientele. In some cases, enslaved cooks could even be “hired out” and potentially accumulate their own money

Outside of Charleston, there were other plantation chefs with exceptional training and ability. At Mount Vernon, George Washington’s chef, Hercules, was widely acknowledged to be a “celebrated artiste“. And Sally Heming’s brother James went to Paris with Thomas Jefferson and came back the chef de cuisine of Monticello.

Paris was then the culinary capital of the world, and Hemings spent five years in the city, mastering the art of French cuisine. His training was extensive: He apprenticed with a caterer, a pastry chef and even a chef of the Prince de Conde, who was known for the splendor of his table.

Famously, Jefferson also brought back a quartet of waffle irons from Europe, which James undoubtedly knew how to operate.

If they weren’t formally trained away from home, plantation cooks usually underwent lengthy, practical apprenticeships working in plantation kitchens as assistants to the head cook. (Kelly Fanto Deetz’s chapter, “Stolen Bodies, Edible Memories”, in the Routledge History of Food is very good on this topic.)

No matter how they were trained, in the Southern slave economy good cooks were worth a lot of money, in fact, the only enslaved people worth more were experienced carpenters. Cooks were worth so much because entertaining and food were so important to southerners, so, for example, if on a moment’s notice you wanted to celebrate the return of James Monroe from two years in Paris, your “negro cook” could walk straight into the parlor of your elegant Richmond home…

…holding before her an immense tray of batter, while behind her came a negro boy with two or three pairs of long-handled waffle-irons. Nothing abashed by that goodly company, the old cook walked straight up to the fireplace where a wood fire was burning and then and there proceeded to make her waffles with a dexterity, quickness and perfection which some other Virginia cooks might have equalled but which none could surpass. They were served ‘pot and hot’ with superb butter and other accompaniments, and enjoyed intensely by all present, but by none more than Mr. Monroe. The lady of the house confessed that the proceeding was rather odd. ‘But,” said she, “I knew Mr. Monroe — poor man — hadn’t had any waffles fit to eat since he left Virginia; and I was determined he should have some.”

In Springfield, Massachusetts, the waffles produced by Emily the pastry chef and Mary Sly the cook were worth a lot of money to Uncle Jerry. I’ve not been able to learn much about Emily. I suspect that she was a former enslaved person, but I can’t say for sure. Mary Sly, however, was a former slave, either a runaway or self-emancipated, one who had an interesting history.

In the 1840s and 50s, Springfield was probably the second most anti-slavery town in the entire country, behind Oberlin, Ohio. John Brown was there worshipping at a black church and going spectacularly bankrupt. And Sojourner Truth was just down the road in Northampton, in a utopian commune trying to grow silk worms. Even before that, however, starting in the early 1830s, the Reverend Samuel Osgood of the First Congregational Church — attended by Uncle Jerry and Aunt Phoebe — had begun speaking out and organizing against slavery.

What’s odd about that last fact is that, until his death in 1835, Mary Sly’s one-time owner, a man with plantations in Mississippi and Louisiana, was an active member of that congregation.

But, that’s a story I’ll have to tell in part two, as the search takes us south of the Mason-Dixon, where in 1806, we’ll find what might be the earliest appearance of fried chicken and waffles, as a footnote in a dramatic incident in the life of a future American president.

Thank you for reading. I’ll publish part two of “A History of Chicken and Waffles” next Monday. In the meantime, subscribe for regular updates if you haven’t already done so, and be sure to follow me on Twitter and like An Eccentric Culinary History on Facebook.

I grew up near the site of the Schuylkill Hotel! A consultation with my siblings revealed that we all ate catfish waffles at a local parish benefit dinner we were dragged to when we were 8, 11, and 14. The consensus seems to be the waffle was the being the best part. Thank you for the memory!

This was a while ago and the parish school is now high-end apartments. It was a predominately Italian immigrant Catholic church and the cat fish and waffles sat next to spaghetti, lasagna and beef in gravy. Don't remember which pan emptied first but there was always a lot of beer flowing.