It was was generally acknowledged in the second half of the 19th century that few things were worse than an Irish cook. Their awfulness was proverbial.

“Many things are called crimes that are not as bad as the savagery of an Irish Cook.” ~Amelia Barr

American newspapers and ladies magazines were filled with stories about burnt roasts, inedible white bread, tardy dinners, and insolent servants. The “domestic problem”, i.e. the problem with Irish domestics, was the topic of the day, and there seemed to be no solution.

But what was one to do? In post-Civil War, Industrial America, urban, middle-class women were overwhelmed with domestic duties. The keeping of a respectable home was not something to be essayed alone. In the era before labor-saving appliances, a housewife needed a young woman who could cook and clean at her direction. Unfortunately, native-born Americans, the citizens of a free republic, generally declined to go into service. It was beneath their station, no matter how destitute they might be.

So, the middle class was booming, labor was scarce, domestic help was dear, and the Irish were available. A young Irish woman who could make her way to America could command a pretty wage, three dollars a week with room and board, or more if she were clean and her references good.

And, make their way they did, by the hundreds of thousands. In the decades after the Civil War, single women comprised the largest category of Irish immigrants, 53% of the total. The Irish were the only immigrants in the entire 19th or 20th century whose women coming to America outnumbered the men.

Unfortunately for the husbands and children of their new nation, these young women did not know how to cook, at all, and seemed resistant to learning.

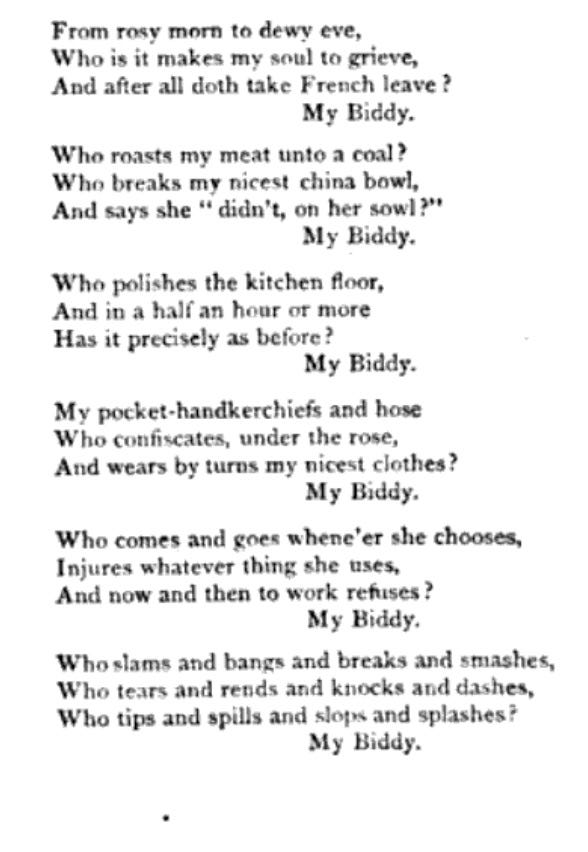

Biddy is to Bridget as Paddy is to Patrick, the catchall name for an Irish worker. This young “Biddy” soon became the villain of many a domestic comedy, called out as such because of her surly independence and cack-handed ways at the stove.

More than a bad cook, Biddy was also, according to Diocletian Lewis, the Dr. Oz of the 1870’s, a threat to national health.

In a chapter entitled “Biddy O’Flaunnigan as Cook,” Dr. Dio Lewis touches upon a subject of the greatest importance to every one of us, man, woman, and child. It is that of entrusting the preparation of our food, which is to form the brains, bones, and muscles for ourselves and our children, to an ignorant Irish woman who, perhaps, a month ago was living in a mud hut on a diet of potatoes…”

~Philadelphia Evening Telegraph, December 12, 1870

The first and biggest problem was that Biddy arrived in America uneducated in the ways of keeping house, and the American housewife, the dainty “Miss Lucille,” was charged with whipping her into shape, whether Biddy wanted to be whipped or not.

They have had no experience in nice housework, no habits of cleanliness or economy – for the lowest laboring class is never saving – nor even an education often in the simplest kinds of cooking . . . The consequence is that each house is, at some time or other, a kind of philanthropic ‘Servants’ Institute’, where a blundering, slovenly, strong-armed maiden is educated into a neat, handy, serviceable house-helper.

~ New York Times, 13 December 1863.

It’s not surprising the Irish girl couldn’t cook. The average age of the young Irish women who immigrated in the 19th century was 21 years old. Many of them were in their mid-teens, 15 or 16 years old, from impoverished rural homes, unused to the lack of autonomy and long hours of drudgery required in domestic service, where 14-hours days, six-and-a-half days a week, was the norm.

Oddly, despite being ignorant of middle-class domesticity, at the same time, Biddy was surprisingly literate.

Although they generally came from poor farming families, many had the rudiments of literacy, especially in comparison to immigrants from the continent. In Ireland, both the traditional “hedge schools” and the National Schools, which opened in 1831, emphasized literacy. During the nineteenth century, the percentage of Irish with basic skills in reading and writing rose from around 30 percent in the 1830s to 75 percent by mid-century, culminating in a rate of 97 percent in 1900, higher than for the general American population. These averages tended to be highest among the young, and most immigrants were young.

And this was probably the real root of the problem.

"For several years, Irish incapables have reigned in our kitchen and general discomfort has pervaded the house.” ~Louisa May Alcott

You know things are bad when even the wonderfully sympathetic Louisa May Alcott is complaining about you.

“No Irish need apply,” said Louisa May Alcott, because she had another solution to the problem of keeping house. She would hire an American woman and treat her like a sister.

My little Miss S. was one of the family, for in the beginning I said to her, “I want someone to work with me as my sisters used to do. There is not mistress or maid about it, and the favor is as much on your side as mine. Work is a part of my religion and there is no degradation in it, so you are as much a lady to me, cooking my dinner in the kitchen, as any friend who sits in the parlor. Eat with us, talk with us, work with us; and when the daily tasks are done, rest with us, read our books, sit in our parlor and enjoy all we can offer you in return for your faithful and intelligent service.”

And that’s exactly what Alcott did, to her great satisfaction, and to the benefit of an otherwise destitute American woman.

This is the most peculiar, Dickensian, part of this whole story, when you realize that in the middle of a historic labor boom, when Irish girls, fresh off the boat, could command sumptuous wages for mangling dinner, there were respectable American women who were going hungry for lack of work. Women who were experienced and capable cooks.

In the years after the Civil War, starvation, or at least malnutrition, was a real possibility for many women. Thanks to bloodbaths like the battles of Antietam, Shiloh and Chickamauga there weren’t enough young men to go around, and impoverished widows and spinsters were legion. No level of desperation, however, could force these women into domestic service, they were too American, too republican, too proud for that. They’d rather starve than become a domestic.

This is why Louisa May Alcott is treating her cook, “little Miss S.”, with such exaggerated civility. (“I always gave her her name as she gave me mine, and returned the respect she gave me as scrupulously as I could.”) It is only by pretending that their relationship was not that of mistress and maid that Miss S. was able to maintain her dignity and work for Alcott. They pretended Miss S. was not the cleaning lady and cook. She was just a friend who was helping out at $3 a week plus room and board.

By the way, this is the same reason why, today, American waiters always insist on introducing themselves by their first names, and why middle-class American women prefer maids who aren’t native speakers of English.

Which brings us back to Biddy and her rebellious ways.

Biddy was a native speaker of English, comically accented English, but English nonetheless. And Biddy was literate and pretty darn smart, even if she didn’t know how to cook. Most importantly, she was, above all else, an American in embryo.

In English popular culture, on the stage and in novels, the Irish servant was caricature of fun, inept but good natured and not especially querulous. But in America, the Irish Biddy was a terror, she wrecked your meal and bullied your family. The difference is, Britain had a well-developed class system, one in which everyone knew their place. While in America, not so much. (Andrew Urban of Rutgers University has a good paper on the phenomenon of the rebellious Biddy.)

In other words, Biddy bridled because Biddy was becoming American.

Biddy was becoming American. How could it have been otherwise? The Irish girls made good money, read a lot of books and newspapers, and had no intention of going back to Ireland. They were dead set on becoming American, and being American meant republicanism, egalitarian manners, and showing and being shown proper respect. Imagine how prickly our little Miss S. would be if someone tried to boss her around. She absolutely wouldn’t stand for it, and neither did Biddy after a few months in America. There were plenty of desperate housewives in 19th century New York and Boston, and jobs for cooks who couldn’t cook were plentiful.

One more point, this is an urban problem, the problem of a fast-rising, newly-urbanized American middle class. In the 19th century, out in the country, most prosperous farms had servants—farmhands and maids— who ate at the same table with the owners, and expected their condition to be temporary. Eventually, the farmhand would buy his own farm and marry the maid, who would then keep house for their new family. And thus republican dignity was maintained.

This new urban middle class, however, wanted a permanent servile caste, one which had no hope of advancement up the ladder. If you were rich enough, you could import as your servants an English butler and nanny, a French cook and maids, people who were accustomed to a rigid class system and knew their place. That was the ideal to which the middle-class American housewife—reading her English novels and mimicking the English manners—aspired. But Biddy O’Flaunnigan would not conform to that. She was determined to be American, with all that implies, and no lady novelist putting on airs was going to stand in her way.

And, worse, Biddy was going to remain Catholic. Another element of the tension between housewives and their Irish cooks was the religious differences between the two. At a moment when American missionaries were triumphantly converting “heathens” in China, the Irish domestics remained intractably papist, despite being subjected to, “a most trying ordeal of temptation and persecution on account of their religion.” If I were more talented, I’d write a one-act comedy about Louisa May Alcott trying to explain Protestant Transcendentalism (“work is part of my religion”) to Biddy, then giving up and tricking a meek Presbyterian woman in to doing the drudge work.

What finally ended the terror of the Irish cook was two things, the Great Migration and modern appliances. By the turn of the century, Blacks had begun to move from the south to the north in record numbers, supplanting the Irish as the preferred domestics in the Northeast. And, unlike the Irish girls, the black women who replaced them in middle class homes had reputations for being uniformly good cooks. (There’s a lot more to say here about this, a lot more, but I’ll come back to it in the future. It is, as you would imagine, a very fraught topic.)

Eventually, of course, machines replaced everyone except the lone and lonely housewife. The washing machine, dishwasher, vacuum and microwave took over completely, to the point that unless you’re quite wealthy, the only domestic seen in most middle class homes today is a Central American woman who shows up once a week to clean the bathrooms.

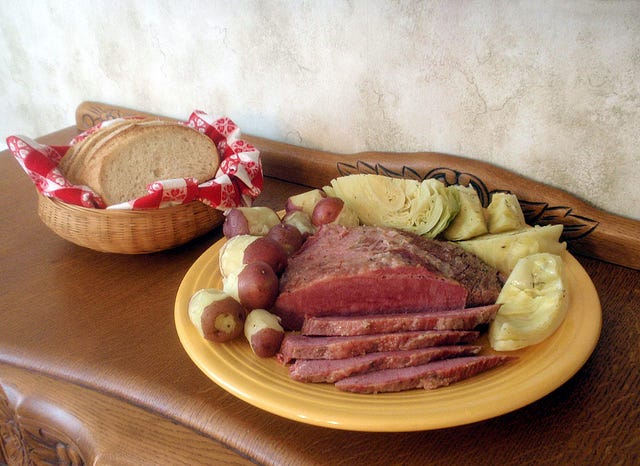

But, back to Biddy at the stove one last time. I want to point out, in honor of St. Patrick’s Day, that the glory of Irish-American cooking is boiled meat.

Literally, the easiest and most foolproof dish possible is the pinnacle of Irish-American cuisine. I do not think this is a coincidence.

Happy Saint Patrick’s Day!

Thanks for your attention and support. I’ll be back on Monday with something new. In the meantime, please follow me on Twitter and like me on Facebook. Cheers!

And you didn't even include Typhoid Mary Mallon who had to be forcibly quarantined for two decades to keep her from pursuing her cookery career.

My grandmother was a certified Irish cook in some rich guy's house on the Main Line in Philadelphia where she had to learn how to cook French food and supposedly thought very little of it. But my favorite quote about Irish cooks from Irma Rombauer's Joy of Cooking intro to hash recipes: "The Irish cook, praised for her hash, declared: "Beef ain't nothing. Onions ain't nothing. Seasoning's nothing. But when I thro myself into my hash, that's hash!"