The Great Sushi Craze of 1905, Part 2

In Part One of “The Great Sushi Craze of 1905” I introduced to you what might have been the first real Japanese restaurant in the United States, a bare-bones place that opened in the summer of 1889 at 84 James Street in downtown New York City. That year’s August 31st issue of Harper’s Weekly gave this unnamed restaurant a five-star review, complete with an engraving of stout Americans in pince-nez giving their order to a prissy waiter.

If you recall, the story of the possible first Japanese restaurant ended with a cliffhanger, a curious newspaper clipping that reported that the restaurant had closed for good on September 1st, the day after Harper’s Weeklypublished its review.

The reporter and his guest went elsewhere for dinner, after having discovered the only case on record where a restaurant closed up on account of a splendid free advertisement that would have brought it patronage and wealth.

But that story told to the reporters was a lie.

The truth was that the rooms at 84 James Street, rented by the would-be restauranteurs, the “fat-faced, clean-looking” Charlie Eymoto and his “white wife”, were also operating as a flophouse for Japanese sailors. And by the end of 1889, 84 James Street would be notorious as the location of two separate crimes.

Ka Ku Kura, a fifteen-year-old girl, the “pearl of the Kai family”, was supposedly taken by unknown persons on September 1st, 1889. Five days later, the police burst into 84 James Street and found her there, alive and unmolested, reporting piously that no “indignities had been offered her.”

After a long day of palaver, involving translators and Charlie Eymoto and his wife, the real truth emerged. Ka Ku’s devoted father and mother were not her parents, but instead unrelated ne’er-do-wells who had brought Ka Ku and another girl to America to “become inmates of a house which [they] intended to conduct in New York.”

Learning this, and being disinclined to submit to a life in the demimonde, Ka Ku ran away and found refuge with the sailors at 84 James Street, at which point false-father and would-be-brothel-keeper Kai Kura summoned the police to help find her. In the end, Ka Ku was sent home to Japan and, sad to say, Kai Kura and his wife were released back into the wild.

Two months later at 84 James Street, on November 10th, 1889, the second notorious crime occurred when out-of-work sailor Shibuya Jugiro picked up a kitchen knife and stabbed fellow sailor Mura Commi to death. Charlie Eymoto testified at the trial, the jury deliberated ten minutes, and Shibuya Jugiro went to the electric chair.

Prior to 1885, the majority of the Japanese who had made it to America came as students, and most of them were either aristocrats or the sons of samurai. For example, in 1879, the valedictorian of the graduating class at Hope College in Holland, Michigan, was a defrocked samurai, named Ogimi Motoichiro, who delivered his commencement speech in both Latin and Japanese.

The denizens of 84 James Street were not the Hope College-educated sons of samurai; they were Japanese of the lower orders, the sort that had begun to arrive in America to labor in mines, farms, steam laundries and restaurants. A rough and ready crew who worked hard and cheap and competed directly with American laborers and small businessmen. The exact sort of Americans who had helped drive the Chinese out of the country just a few years earlier, and would help end Japanese immigration a few years hence.

But, before that happened, those same working-class Americans discovered that what Harper’s Weekly had said about Charlie Eymoto’s place, was true about many places.

Last of all, but of equal interest to the reader, is the fact that the Japanese favor economy and low prices. A superb meal with them costs not more than a quarter of what it would under American or European auspices. From the first to the last their dinners are good, delightful and very cheap.

Very cheap.

A clipping from the February 2, 1905, issue of Pendleton, Oregon’s newspaper, The East Oregonian

Before we continue, we must make a distinction between the two kinds of Japanese restaurants: Japanese restaurants that served Japanese food, like the one at 84 James Street and Japanese restaurants that served American food, like the one in Pendelton, Oregon.

Starting in the late 1880s, the Japanese restaurants that served American meals were suddenly everywhere in the west. For the next twenty years, Japanese-owned dining houses from Los Angeles to Seattle to Houston served up a decent meal of meat, potatoes, bread and butter, coffee or tea, to anyone who had a dime.

You can get a good idea of what a meal was like at a ten-cent restaurant from a review in the July, 1902, issue of The American Kitchen Magazine.

One of the novelties of Seattle appealing to the Easterner is the Japanese restaurant. There are several such, which by their competition have lowered the prices in every restaurant in the city until one can buy good food as cheaply here as in any city of the country.

The meal was breakfast, and the restaurant of choice was the Queen City Restaurant, located at 114 Occidental Avenue, Mr. Charles Sasaki, proprietor.

Let us sit down and order a plain steak and see what we get. First will come a little bowl of oatmeal and milk; spoons and sugar and bread are already on the table, so you fall to and find that the oatmeal is good, very good, indeed, in fact. The bread, too, while it is unmistakably baker’s bread, is pretty good. The waiter will remove the bowl and set before you your steak. It is well cooked, about the size of the palm of your hand, and — wonderful to relate — as tender as you could hope to get in any restaurant in any place, regardless of price.

Sadly, the coffee was not so good.

One is disposed to grumble over the coffee till the waiter drops the check in front of him, and it is for ten cents only!

Almost immediately after the appearance of the ten-cent restaurants, problems started in Spokane, Seattle, Denver and San Francisco, where Japanese restaurants were seriously underpricing American-run dining houses. Until the Japanese arrived, the going rate for a full meal had rarely been less than a quarter, four bits in the mining camps.

It is not an exaggeration to say that ten-cent restaurants did more to harm to Japanese-American relations than anything between Commodore Perry and Pearl Harbor.

By 1900, Japanese restaurants were putting American restaurants out of business. The response to this came not from American restaurant owners, but from their employees, who in Spokane, Washington, were organized as Local 485 of the Waiters and Cooks Union, a rising labor organization that had recent success in Chicago and San Francisco.

In 1902, Spokane’s Local 485 organized a boycott of a ten-cent Japanese restaurant run by a Mr. K. Takahashi. Unfortunately, it was an imperfect tactic, one that did not succeed, mainly because it was hard for workingmen to turn down a cheap meal. So hard, that the union had to institute a $2.50 fine for any member caught entering a Japanese restaurant.

But there were some successes. In 1907, unions and American restaurant owners succeeded in convincing the Seattle city council to mandate a fifteen cent minimum price for a meal, erasing part of the Japanese price advantage.

And in San Francisco, in December of 1906, unions conspired with the corrupt mayor, Eugene Schmitz, former head of the Musicians Union , to get Japanese children banned from public schools.

But the Japanese restaurants still prospered, as did the cut-rate Japanese barbers and laundrymen.

On May 20, 1907, however, things blew up. A group of union men caught four of their fellow unionists eating at the ten-cent Horseshoe Restaurant at 1213 Folsom Street. Beatings were handed out to the two men who were foolish enough to exit the restaurant through the front door. A crowd of Barbary Coast hoodlums, who had gathered to watch, turned it into a genuine donnybrook, rushing into the restaurant armed with crowbars, bats, fist and feet, bashing everyone and everything inside.

When the police declined an invitation to become involved, the fun spread to a Japanese bathhouse across the street. The demonstrations resumed again the next night, with less vigor, and four more nights after that, until the police, led by the Japanese counsel, Kazuo Matsubara, stood watch at the edge of Japantown.

In their favor, the police did have their hands full. At the exact moment the Horseshoe Restaurant was being destroyed by thugs, there were five major strikes going on in the city, with over 10,000 workers idled. The worst was the San Francisco Streetcar strike, one of the most violent labor actions in American history. By the time it ended in March of 1908, 31 people had been killed and more than 1100 injured, the majority of them passengers. Meanwhile, downtown, Handsome Gene Schmitz was in court, being tried and convicted for corruption.

For Washington, however, the most important thing happening in San Francisco was that the trashing of the Horseshoe had become an international incident.

Over the coming weeks, newspapers in both countries, including William Randoph Hearst’s San Francisco Examiner, whipped up the war frenzy. Opposition politicians in Tokyo called for war, while a group of high-ranking Japanese officers argued they could defeat the Americans in the Pacific (and probably could have).

Teddy Roosevelt dispatched special commissioners to investigate, and the Great White Fleet to intimidate. It worked. The Japanese had second thoughts about war, and racial and labor tensions were calmed for a few years.

A clipping from the Warren Sheaf, Warren, Minnesota, November 15, 1905.

Of course, by 1900, there were also plenty of Japanese restaurants that served only Japanese food. Most of them were located in the Japantowns that appeared wherever the Japanese lived in substantial numbers. (By 1940, California had several dozen Japantowns, many in tiny rural places you’ve never heard of, like Brawley, Cortez and Fowler. The majority of Japanese immigrants were not city dwellers, but farmers who preferred rural lives to urban lives.)

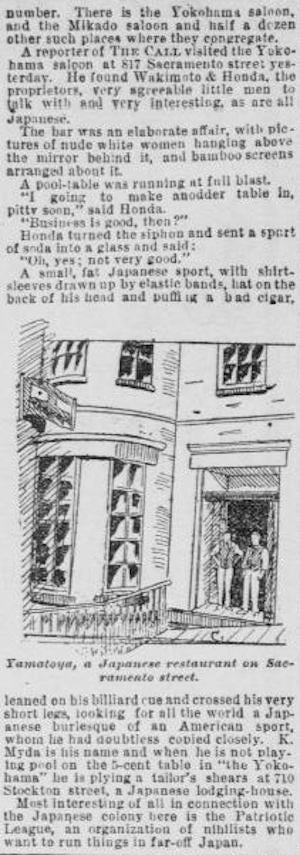

The first of the Japantowns to emerge was in San Francisco, along two blocks of Sacramento Street on the edge of Chinatown. The first mention I can find of a specific dining establishment in that area is from November 1st, 1891, when it was reported in the Morning Call that two Japanese “men’s clubs” the Darkockya at 922 Sacramento and the Yamatoya at 935 Sacramento, had been fined for failing to pay their liquor taxes.

A few months later, on May 4th, 1892, in an article in the Morning Call titled “Japanese are Pouring In”, the Yamatoya is referred to as a “Japanese restaurant” in a caption for an accompanying sketch. (Presumably, those two figures standing in the door in their vests and shirtsleeves, are Japanese “sports”.)

Whatever the case, Japanese restaurants had by then already appeared in San Francisco, perhaps appeared even before the restaurant at 84 James Street in New York had opened and closed its doors. More research needs to be done to clarify the matter.

We do know that Americans had already developed a taste for asian food, thanks to chop suey, and were probably among the patrons of some of these early Japanese-Japanese restaurants. By 1905, Americans were even eating at Japanese noodle houses, where udon, or a bowl of “noodle soup” (ramen by another name), were only a nickel. These “noodle joints” were usually located in the worst part of town, catering to the worst and poorest clientele. In Ogden, Utah, they were especially louche spots, notorious for gambling and liquor, and the newspapers of the era record plenty of fights, robberies and raids.

In 1907, spurred on by the labor unrest on the West Coast, and by news reports of organized crime and vice in immigrant communities, Senator William Paul Dillingham of Vermont put together a bipartisan commission to invest. When it ended in 1911, the Dillingham Commission issued an enormous, and enormously detailed, 41-volume statistical report, one that provided the justification for restricting immigration in 1924.

The three volumes that dealt with the Japanese, Japanese and Other Immigrant Races in the Pacific Coast and Rocky Mountain States, were prepared by Stanford University economics professor, Harry Mills. They are a goldmine of information about Japanese businesses in 1909.

For example:

Did you get that?

According to the Dillingham Commission, in 1909 in the eleven western states, there were 149 Japanese-owned restaurants that served American meals, and 232 Japanese-owned restaurants that served Japanese meals.

For Japanese-Japanese restaurants, broken out by city, the numbers were: 51 in Seattle, 7 in Tacoma, 4 in Spokane, 1 in North Yakima, 11 in Portland, 33 in San Francisco, 58 in Los Angeles, 28 in Sacramento, 15 in Fresno, 1 in Watsonville, 1 in Vacaville, 3 in Salt Lake City, 8 in Ogden, 10 in Denver, and 1 somewhere in Idaho. (There were also 2 Japanese-Japanese places in Nevada and 1 in Wyoming.)

These numbers also don’t include restaurants east of Denver, such as those in New York City (of which there were several), the Tokyo Restaurant in Minneapolis, and Tom Brown’s Eagle Cafe in Houston, along with probably dozens of others in western towns too small for the commission to send its agents to. All told, there may have been as many as 300 Japanese restaurants serving Japanese food in America in 1909.

Simply put, by 1910, you could get an authentic Japanese meal in most major American cities and dozens of small towns in Washington, Oregon and California.

Finally, we come to the cause of the Great Sushi Craze of 1905.

One of the reasons why Japanese naval officers were confident in 1907 that they could defeat America in a Pacific war, was because they had recently obliterated the Russian navy in the Russo-Japanese War, a result that had shocked the world.

In fifty years, Japan had effected a remarkable transformation, from isolated feudal state, to modern industrial powerhouse and imperial giant, owner of Manchuria and Korea.

The year 1905 began on January 2nd, with the Japanese capture of Port Arthur (today the Chinese Lüshunkou District) after the destruction of the Russian Pacific fleet in December. Five months later, in May, the Japanese navy destroyed the Russian Baltic fleet, which had sailed around the bottom of Africa to get to the battle. At that point, the war was over. All that remained was for Teddy Roosevelt to broker the Treaty of Portsmouth and collect his Noble Peace Prize.

And, for the first time since the Mongols rode off into the sunrise, an Asian nation had defeated a European power.

But, here’s the thing that should shock you, especially those of you who think that all 19th and early 20th century Americans were total racists: most Americans were rooting for the Japanese.

A clipping from the Minneapolis Journal, dated November 23, 1904.

Here’s a transcription of the relevant part:

Miss Major, a Japanese nurse, was the honor guest, and added to the pleasure of the afternoon with stories of home life. Saki was served in real Japanese dishes and later little Japanese baskets of confections formed the first course for a menu which included rice to be eaten with chopsticks, raw fish, tea and Japanese cakes.

Sashimi in Minneapolis! In 1904! In the middle of the Russo-Japanese War!

Miss Major is likely one of two sisters, Ione and Helen Major, both born in Japan of an Italian (or American) father and a Japanese mother, both of whom were employed in 1900 as professional nurses at Northwestern Hospital in Minneapolis.

You know who else was a Japanese nurse in 1904?

The future Empress Teimi of Japan, the wife of Crown Prince Yoshihito and mother of 3-year-old, future-emperor Hirohito, that’s who.

Let us stipulate that in 1905, Japanese nurses were way sexy.

In fact, in 1905, everything Japanese was sexy and exciting and desirable.

And, now, this is going to be really, really hard for some of you to believe, but prior to 1920, forget Japanese women, Japanese men were the real sex symbols.

I’ve mentioned two Japanese men, H. Ohnick and Charlie Eymoto, who were married to American wives. But in my research, I’ve encountered dozens of them, like Matsudaira Tadaatsu, the brother of the last feudal lord of Ueda, who graduated from Harvard in 1879 and married Miss Carrie Sampson, a bookseller’s daughter. He stayed in America and became the city engineer of Bradford, Pennsylvania, and later an inspector of mines for the State of Colorado.

Speaking of 1905, here’s another mixed couple, from the New York Tribune, March 13, 1905.

A real Japanese room set down in a New York drawing room will constitute an appropriate setting for a Japanese entertainment to be given next Wednesday afternoon, March 15, at the home of Mrs. Jokichi Takamini [sic], No. 45 Hamilton Terrace, for the benefit of Japanese girls orphaned by the present war.

This room which is twice the size of an ordinary New York apartment room, represents an autumn scene, with painted scenery, rare works of art in bronze and porcelain, and the dwarf trees in which the Japanese so much delight. It was exhibited at the St. Louis Exposition, and was afterward purchased, together with a spring room, by Mr. Takamini, the spring room having been set up at the country home.

Mrs. Takamini will receive her guests in the autumn room gowned in Japanese style, for though she is an American woman, she has many beautiful Japanese robes, which she often wears at social affairs.

Mrs. Takamine, was originally Miss Carolyn Hitch of New Orleans; Dr. Jokichi Takamine, the son of a samurai-turned-physcian, was a Berlin-educated scientist. When they were finally married in 1887, after three years of acquaintance, the Times Picayune editorialized, “A Brilliant Wedding… The sequel to a happy love affair.” (Their grandson, the late Dr. Jokichi “Joe” Takamine III, invented the Malibu addiction cure.)

I’m not saying that Americans before WWI weren’t racist. What I’m saying is that the Japanese occupied a place denied to all other non-whites; they were effectively honorary whites.

Until labor unions began to agitate on the West Coast around 1900, there wasn’t a fatal social stigma to an American woman marrying a Japanese man. It wasn’t even illegal in the South. In fact, the first big interracial marriage hoo-haw concerning a person of Japanese ancestry didn’t occur until 1910.

After that, public racism got really nasty, as newspapers, labor unionists and politicians shouted the Yellow Peril to the heavens in an attempt to end Japanese immigration. And it worked.

But, I don’t want to end this long journey on a sour note. I want to soak for a little bit longer in the sweetness of 1904 and 1905.

I’ve called this post the “Great Sushi Craze of 1905”, because 1905 was when the Japan-o-mania seemed to peak, just after the end of the Russo-Japanese War. (Remember the clipping of the sushi party in Bismarck, North Dakota, I showed you in the Part One? It took place on May 7th, 1905.)

In truth, however, the Japanophile craze had been building for a long time. From 1898 through 1907, the social pages of American newspapers were filled with descriptions of Japanese-themed social events, while the women’s pages had instructions on how to organize your own Japanese soirees and teas. During the same period, home design magazines told you how to convert your sitting room into a Japanese tea-house (a fad of the late 1890s) and gardening journals discussed Japanese plants and landscaping trends.

In 1906, as the mania began to wane, there was one final hurrah: two separate American newspaper syndicates sent out to their subscribers, at almost the same time, recipes for sushi.

Smarter publications advised simply hiring a Japanese cook.

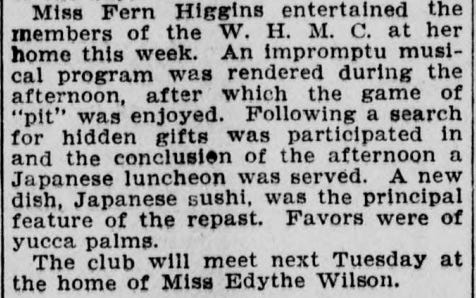

Finally, as a reward for your patience, I present to you the delightful Miss Fern Dell Higgins of Santa Monica, California, as seen on the society pages of the Los Angeles Herald, August 18th, 1904.

My transcription:

Miss Fern Higgins entertained the members of the W.H.M.C. at her home this week. An impromptu musical program was rendered during the afternoon, after which the game of “pit” was enjoyed. Following a search for hidden gifts was participated in and the conclusion of the afternoon a Japanese luncheon was served. A new dish, Japanese sushi, was the principal feature of the repast. Favors were of yucca palms. The club will meet next Tuesday at the home of Miss Edythe Wilson

And there you have it, the first mention of sushi being eaten in America by Americans, August 18, 1904

I’m half in love with this wonderful, 17-year-old flibberty-gibbet, Fern Dell Higgins. She lived with her father and stepmother at 310 Colorado Street in Santa Monica, exactly where the Bloomingdales is in Santa Monica Place, three blocks from the pier.

Mentioned frequently in the society pages through 1910, Fern Dell strummed the guitar, sang light songs, published jejune poetry, wrote bad music, played field hockey and acted in amateur dramatics. Later on, she even had two patents to her name. And, by the time she was 30, she was twice divorced and making her own way in the world.

In the late 1920s, as Fern Dell Hunt, she became the first female bond salesman in California, working for Blythe-Witter & Co (the predecessor of Dean Witter) helping widows invest their money. She’d started in the secretarial pool and moved up to the executive suite.

In 1930, on the knife’s edge of the depression, she married for the third time to Dr. William E. Gamble, an emeritus professor of ophthalmology, retired from the University of Illinois, and 26 years her senior. They spent 18 years happy years together in Santa Monica before he died in 1948, leaving behind the “devoted and interesting companion of the good years of his retirement, and at the last, his skillful, kind and constant nurse.” Fern Dell Gamble lasted six more years, dying in 1954.

And, fifty years earlier, in 1904, she served her friends a new dish, Japanese sushi.

N.B. Here’s the link to Part One of the Great Sushi Craze of 1905.

P.S. If you enjoy this sort of longread food history, you should follow me on Twitter, and like An Eccentric Culinary History’s Facebook page.

P.P.S. You may also enjoy my objection to the practice of serving food in Mason Jars.