The Great Sushi Craze of 1905, Part 1

The official history of Japanese food in the United States says that Americans didn’t get a taste of raw fish and vinegared rice until the late 1960s, when groovy Hollywood stars and trendy Buddhist humbugs began turning the squares onto the best thing since sliced bologna: sushi.

But that’s wrong. The truth is that two generations earlier, in the first two decades of the 20th century, Americans knew all about Japanese food and enjoyed it so much that labor unions and American restaurant owners conspired to run the Japanese out of business and out of the country. Worse, these angry agents of change were mostly successful in that effort, launching a thirty-year-long campaign of hysteria, intimidation and misinformation, one that ended in 1924 with the passage of the Japanese Exclusion and Labor Act.

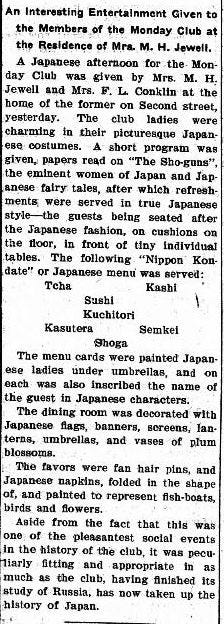

But first, here’s a clipping from a North Dakota newspaper, dated May 11th, 1905.

Sushi in North Dakota in 1905! I bet you weren’t expecting that.

So how did Americans, living before the Great War, know so much about the Japanese and their cuisine? And why did we forget it?

That story, like most of my recent stories begins with the California Gold Rush. The discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill in 1848 fundamentally reordered America and the wider world. It wasn’t just that the world rushed in, it’s that we also rushed out.

Americans began the second half of the 19th century as provincial bumpkins who rarely left the continent, and ended it as citizens of a highly-literate, highly-mobile society, one fully engaged with and knowledgeable of the far, distant parts of the globe. And the best example of how the Gold Rush changed America and the world is what happened to Japan.

In 1853, just five years after John Marshall’s discovery of gold, Commodore Matthew Perry and a flotilla of American warships sailed into Edo Bay and ended 250 years of self-imposed Japanese isolation. Perry’s mission was to open Japanese ports to American trade, and to establish coaling stations — refueling points — for steamships along the route from China to California. However, what becomes very clear when you read the official letter President Millard Fillmore had Perry deliver is that the gold of California was at the forefront of American minds.

The United States of American reach from ocean to ocean, and our territory of Oregon and state of California lie directly opposite to the dominions of your Imperial Majesty. Our steamships can go from California to Japan in eighteen days.

.

Our great state of California produces about sixty million dollars in gold, every year, besides silver, quicksilver, precious stones and many other valuable articles. Japan is also a rich and fertile country, and produces many very valuable articles. I am desirous that our two countries should trade with each other for the benefit both of Japan and the United States.

California was the only state mentioned in the letter (Oregon still being a territory) because California miners were still strapped for food and supplies. And eighteen days from Japan to San Francisco was better than the one-hundred-and-twenty days from New York to San Francisco.

At the beginning of the second half of the 19th century, the Japanese, like the Americans, were isolated provincials, and like the Americans, by the end of it they were an aggressive, rising, industrial powerhouse.

The change started in earnest when the feudalism of the Tokogawa Shogunate was replaced in 1868 by the forward-looking rule of the 16-year-old Meiji Emperor. Determined to catch up with the West, the young emperor and his advisors centralized power, abolished the samurai class, and invited in hundreds of western experts–French, German, British and American–to help in the remaking of Japan. It would be an understatement to say that they were successful.

One of the most remarkable things about these foreigners, especially the Americans, was how much they loved Japan. Most of them chose to renew their contracts for extra years, more than a few stayed forever, and all recalled their time in Japan with pleasure. Certainly, it helped that the Japanese paid their experts exceedingly well and treated them with enormous respect, but more than that, Japan enchanted visitors like no other place in Asia.

For their part, the American experts introduced the Japanese to everything from brass band music to baseball to apple pie. They also attempted to introduce what most of them would have considered America’s greatest export, Protestant Christianity.

In the 19th century, it wasn’t just trade and good-paying gigs as experts that drove the Americans out into the world. More often than not, it was missionary zeal. The Third Great Awakening was underway, a surge of evangelical fervor wedded to a powerful social message: improve the world, save the world. And Japan was thought to be a prime candidate for both. By the beginning of the 20th century, there were nearly one thousand American missionaries in Nippon, and more than 30,000 converts.

Missionary publications, like the Baptist Missionary Magazine, regularly printed stories about everyday life in Japan, along with accounts of the missionary efforts. Likewise, missionaries who returned from Japan were frequent speakers in churches, lecture halls and on the Chautauquacircuit. This is how the majority of Americans became acquainted with Japanese culture in the 19th century, through the missionaries.

In addition to the experts and the missionaries, American artists flocked to the country starting in the 1870’s. Japanese handcrafts and art, especially ceramics, silk and woodblock prints, were the primary exports that funded the modernization efforts of the Meiji Emperor. Japonisme, caused by the arrival of these goods in the West, blew a giant hole in the European art world, and Impressionism burst out of it. Everyone from Monet to Van Gogh was captivated by Japan, and American painters were no exception. Some of them, such Henry Humphrey Moore, Winckworth Gay, and William Heine moved to Japan to live and work for a few years. The Japanese aesthetic even extended beyond the purely visual, influencing poets like Ezra Pound, and architects like Frank Lloyd Wright.

Finally, for rich Americans, Japan had even become the final stop of an outsized version of the Grand Tour. Ulysses S. Grant led the way. Two months after he quitted the presidency, Grant embarked on a two-and-a-half year tour of the world, with long stops in London, Paris, Berlin, Cairo, Bombay, Beijing and Tokyo. Enthusiastic crowds turned out to greet the ex-president nearly everywhere — 50,000 people in London, 10,000 in Norway. But no one seemed more enthusiastic than the Meiji Emperor, who broke imperial protocol by stepping forward and shaking Grant’s hand, something never before done or imagined by a Japanese emperor.

For his part, Grant reciprocated the affection.

My visit to Japan has been the most pleasant of all my travels. The country is beautifully cultivated, the scenery is grand, and the people, from the highest to the lowest, the most kindly & the most cleanly in the world. My reception and entertainment has been the most extravigant I have ever known, or even read, of.

Simply put, Grant, like every other 19th century American was besotted with Japan.

It’s from Grant’s trip around the world that Americans got one of their earliest accounts of Japanese high dining, given to them in James Dabney McCabe’s 1879 bestseller, A Tour Around the World by General Grant: Being a Narrative of the Incidents and Events of his Journey. McCabe described for his readers an elaborate multi-course state dinner, including a flight of dishes he identified as “shashimi”, perhaps the first time the word appeared in English.

After the shimadai we had a series called sashimi. This was composed of four dishes, and would have been the crowning glory of the feast if we had not failed in courage. But one of the features of the sashimi was that live fish should be brought in, sliced while alive, and served. We were not brave enough for that, and so content ourselves with looking at the fish leap about in decorated basins and seeing them carried away, no doubt to be sliced for less sentimental feeders behind the screens.

Westerners were long familiar with the fact that the Japanese ate raw fish. It had been frequently mentioned and joked about in books and journals since the end of the 18th century. The eating of live fish, however, was an entirely different matter, one unusual enough to elicit many first-hand accounts, such as this delightfully acerbic one from English designer, Christopher Dresser.

Now comes the viand of viands—the most dainty of morsels—the bit that is to the Japanese epicure what the green fat of the turtle is to the city alderman, a dish that is none other than a living fish.

[…]

There is a refinement of barbaric cruelty in all this with contrasts strangely with the geniality and loving nature of the Japanese, for with consummate skill the fish has been so carved that no vital part has been touched; the heart, the gills, the liver, and the stomach is left intact, while the damp algae on which the fist rests suffices to keep the lungs in action. The miserable object with lustrous eye looks upon us while we consume its own body; and rarely is it given to any creature to put in a living presence at it’s own entombment; but, if being eaten is to be buried, this most miserable victims to man’s sensual pleasure actually enjoyed (?) that rarest of opportunities. This cruelty is only practiced by the rich. No living fish ever makes its appearance on a poor man’s table….

Dresser’s account appeared in 1882, the same year that English-American writer Edward Greey published Young Americans in Japan, a bestselling, ripping-yarn, boys’ book, one of a series of at least nine that Greey set in Japan, the first of which was published in 1870.

What I’m showing you with these excerpts — a small sample of a sizable literature — is that 19th century Americans knew perfectly well what people in Japan ate. Not only were there many written accounts, but there were plenty of opportunities to encounter experts and missionaries who’d been there.

In fact, late-19th century Americans knew much more about the world than we, in our self-satisfied ignorance, give them credit for. Most Americans regularly read newspapers and books, and many of them attended public lectures with an enthusiasm we do not share. (We prefer to watch an hour of PBS and call it a day, which is why they wrote so much better than we do.)

But, 19th century Americans didn’t eat foreign food, right? They couldn’t possibly eat Japanese food in America, could they?

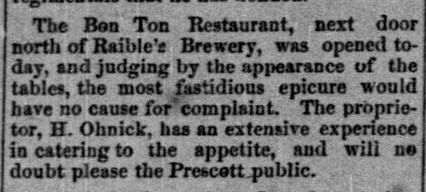

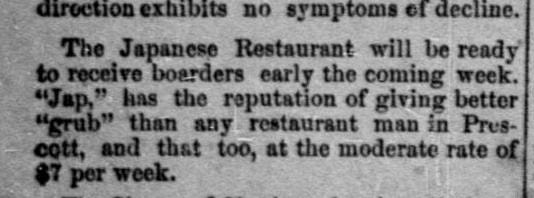

A clipping from the Prescott, Arizona, Daily Miner, dated August 23rd, 1878.

It was the Chinese, not the Japanese who had poured into California during the Gold Rush. For more than three decades after the black ships arrived, most Japanese were legally prohibited from leaving the country, and so the Japanese largely sat out the California Gold Rush except as producers of silk, lacquerware, occasional shipments of food to be sold in California shops.

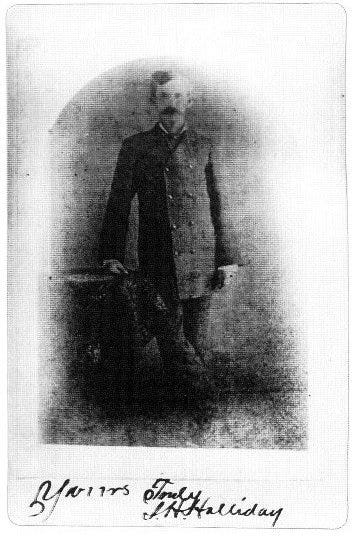

Starting in the 1860’s, as part of their modernization program, the Japanese government did begin to send young men (and sometimes young women) to the West to be educated. Likewise, there were occasional oddball stragglers who somehow ended up in the United States, such as Hachiro Onuki, a lively 27-year-old who was delivered to Boston in 1876, probably as a stowaway in a load of Japanese objects d’art destined for the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia.

But, this movement from East to West was never more than trickle. The 1880 census showed only 148 Japanese in the country. However, in 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, prohibiting the immigration of Chinese laborers. The 1870s had been the decade of the Long Depression, when unemployment and resentment of Chinese workers had both been high. But, as the nation emerged from the slump, and the Chinese were no longer allowed in, the Japanese finally began arrive in greater numbers.

Which brings me back to that curious newspaper clipping from Arizona in 1878. Chinese restaurants had appeared in California almost immediately after the first Chinese stepped off the boat, and by 1850 there were five Chinese restaurants in San Francisco. But what about Japanese restaurants?

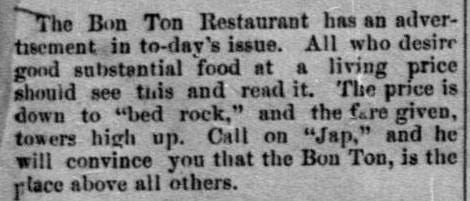

Here are two more clippings from the Weekly Miner, same date, August 23rd, 1878.

And with the revelation that the proprietor of the Bon Ton is H. Ohnick, all becomes clear; the Bon Ton is only a Japanese restaurant to the extent that its owner, Hachiro Onuki, (a.k.a. Hutchlew Ohnick, our stowaway with the now-Americanized name) is Japanese. It served American food.

The only word for Hachiro Onuki’s life is cinematic. After arriving in Boston, he likely worked in the Japanese pavilion at the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia before heading west to, of all places, Tombstone, Arizona. There he found work as a teamster and became a favorite of the locals.

I need to do more research to clear up the chronology of what happened to H. Ohnick in the years immediately after 1878. There is a famous Bon Ton restaurant in Jerome, Arizona, also known as Japanese Charley’s (although it had a Chinese proprietor in the 1890s) which makes me wonder if Ohnick opened a second restaurant, or relocated the original Bon Ton 35 miles down the road to fresh diggins, before selling out.

Be that as it may, Ohnick was soon enough in Tombstone, where he bought property and made friends. When he left the city for good in 1886, the Daily Tombstone ran the following notice:

H. Ohnick, or Jap, as he is familiarly known in this city, has secured a franchise to light the city of Phenix with gas, and will have his plant in operation within the next sixty days. The people of Phenix are to be congratulated upon the acquisition of Jap, for what is their gain is our loss.

Ohnick’s gas lighting company went on to become Arizona Public Service, a major Arizona utility. In 1888, he married Catherine Shannon and was inducted into the Masons. Eventually, he moved to Seattle and founded the Oriental American Bank, dying in Los Angeles in 1921. His oldest son Ben played football on the University of Washington’s football team (during Coach Gil Dobie’s 53-0 run), served in the Army in WWI, and became a lawyer.

I mention all of this because I find it fascinating, but also because in the same May 3rd, 1886 issue of the Daily Tombstone, just six lines higher in the same column, is this notice:

The Tombstone Anti-Chinese League will hold their regular meeting in the City Hall tomorrow evening at 7,30 o clock

The citizens of Tombstone, who were lamenting the departure of “Jap” Ohnick, were also celebrating the departure of the boycotted “Mongolians of Tombstone,” the Chinese workers who had left town the week before, headed to Nogales, Mexico.

And that, in microcosm, was the general attitude of 19th century Americans to both the Chinese and the Japanese; one despised, the other admired. Over and over in newspapers and magazines of the era, the Japanese are praised as a clean, well-bred, delightful race, the “most civilizable” in Asia. The Chinese? Not so much.

So, if the Bon Ton of Prescott, Arizona, wasn’t the first Japanese restaurant in America, what was?

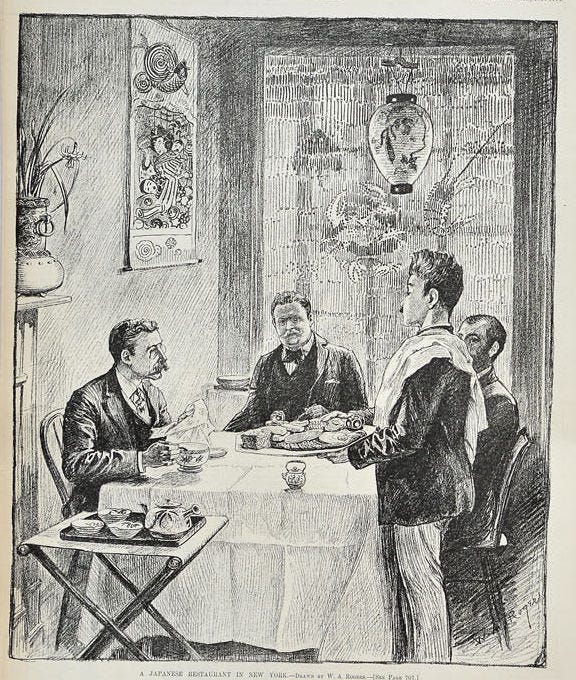

My candidate is one that opened briefly in the summer of 1889 at 84 James Street in New York City. A long review appeared in the August 31st, 1889 issue of Harper’s Weekly, describing the location and food in great detail.

Though they chose as wisely as they knew, the place selected was not the best. With a sublime disregard for fashionable society, the proprietors, T. Yamamoto & Co., picked out a store at No. 84 James Street, near Water, in the heart of the populous district which for forty years has been known as the “Bloody Fourth Ward”

Yep, the Bloody Fourth Ward, a.k.a Gangs of New York, Five Points adjacent. Sublime disregard for fashion, indeed.

So how was the food?

The third course is fish, roasted or broiled. It is served unbroken on a handsome platter, and decorated in a manner altogether Eastern. the favorite style in this respect is to fill one corner of the dish with little blocks of omelet, either plain or highly seasoned; a second corner, with a pile of spinach, with which have been cooked minute pieces of radish skin, carrot, or beet, to give a contrast in color; a third corner with radishes which have been cut into curious shapes that display the crimson of the exterior as well as the white within; and the fourth with mushrooms, ma-tais (an exquisite Eastern esculent) This dish when served is a perfect poem in color. […] It is followed by diminutive fish or meat dumplings, of which the enclosing dough is hardly as thick as a cardboard, and the spiced filling has been chopped into almost a pulp.

Gyoza and artistically carved radishes!

Clearly, this is a true Japanese restaurant, although few of the dishes are given their correct names. Here’s the conclusion of the review.

Last of all, but of equal interest to the reader, is the fact that the Japanese favor economy and low prices. A superb meal with them costs not more than a quarter of what it would under American or European auspices. From the first to the last their dinners are good, delightful and very cheap.

The most peculiar thing is that the restaurant didn’t last a week after the review appeared, in fact, according to wire reports, it closed the next day. Here’s a clipping from the Ohio Democrat, March 1, 1890.

This is a lie. The story of what actually happened to the first Japanese restaurant in America is much, much worse.

You may finish reading my early history of Japanese food in America by going to Part Two of The Great Sushi Craze of 1905.

P.S. If you enjoy this sort of longread food history, you should follow me on Twitter, and like An Eccentric Culinary History’s Facebook page.