Anyone raised on a diet of 1970’s and 80’s pop culture knows what happens when you build a suburb on an ancient Native American burial ground.

It’s a mathematical certainty you're going to have trouble of the hainted kind. And, what with the good silverware spontaneously bending and your small children being sucked into televisions by demons, it’s almost not worth the friendly neighbors, access to shopping, and great school districts, almost.

So, you can imagine my surprise when, shortly after moving into my house two years ago, I stumbled upon an article at the website of the Tennessee Council for Professional Archeology, “Revisiting the Noel Cemetery Site through Basement Archaeology”, that pointed out that I and my neighbors are living on the largest Native American burial ground east of the Mississippi, the so-called Noel Cemetery. (One guess is that the site might have contained as many as 8,000 pre-Columbian graves, making it one of the densest concentrations in North America.)

The occasion of the article was a discussion of the late-2014 discovery of human remains in the basement of a 1930’s home in my Nashville neighborhood. As you can guess, these turned out to be Native American bones, interred in the pre-Columbian period by the Mississippian people in a very typical stone-box grave, and then uncovered during a home renovation project. But, more about stone-box graves in a second.

What really set me back was a photo that accompanied this article.

That’s my basement. I mean, THAT’S MY BASEMENT!

Or, at least, it looks exactly like my basement, down to the exposed floor joists and wiring, packed dirt and black plastic. Here’s a photo I just took in my basement.

For a day or two, in the spring of 2020, this first photo was a big deal in my home. I live in a house built in the 1930’s, on the edge of a hill overlooking Brown’s Creek, which is the central terrain feature of the Noel Cemetery. So, you can imagine the hubbub. My youngest daughter, then 14, was convinced that our basement is haunted, even after I figured out that the similarities were superficial. The bones in the basement found in 2014 were not found in my basement, it just looked like my basement. Haunting cancelled.

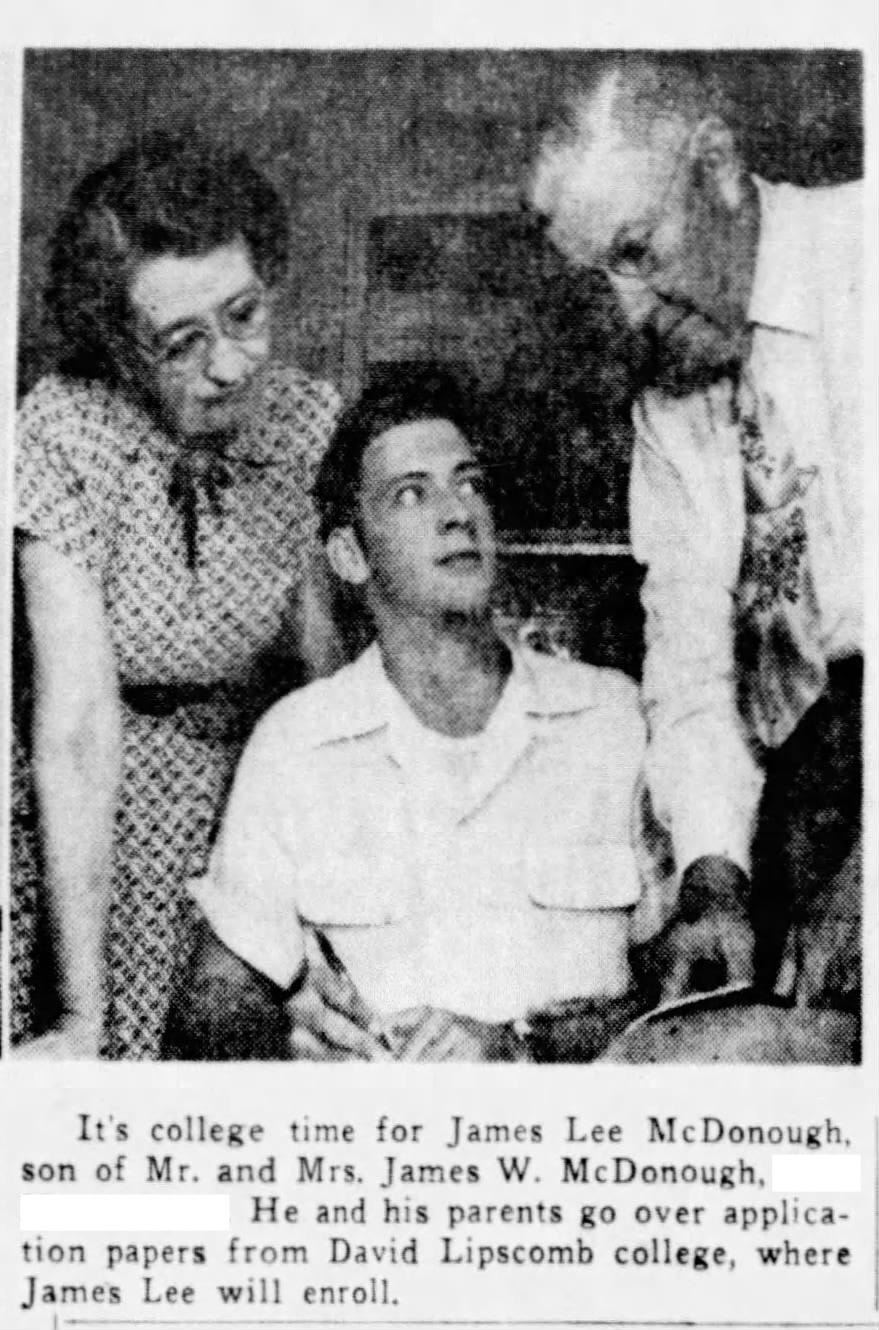

By the way, my house was built in 1934 by James W. McDonough, the postmaster at what was then David Lipscomb College. It was the childhood home of James Lee McDonough, the Civil War historian, a delightful man whose best-selling biography William Tecumseh Sherman: In the Service of My Country: A Life I heartily recommend.

I haven’t seen James Lee since COVID, but he called me the other day because a mutual friend had told him I’m living in his old house. I forgot to ask him if there were any graves in the basement, although I did promise to give him a copy of this photo I pulled out of the Nashville Tennessean, dated 1952.

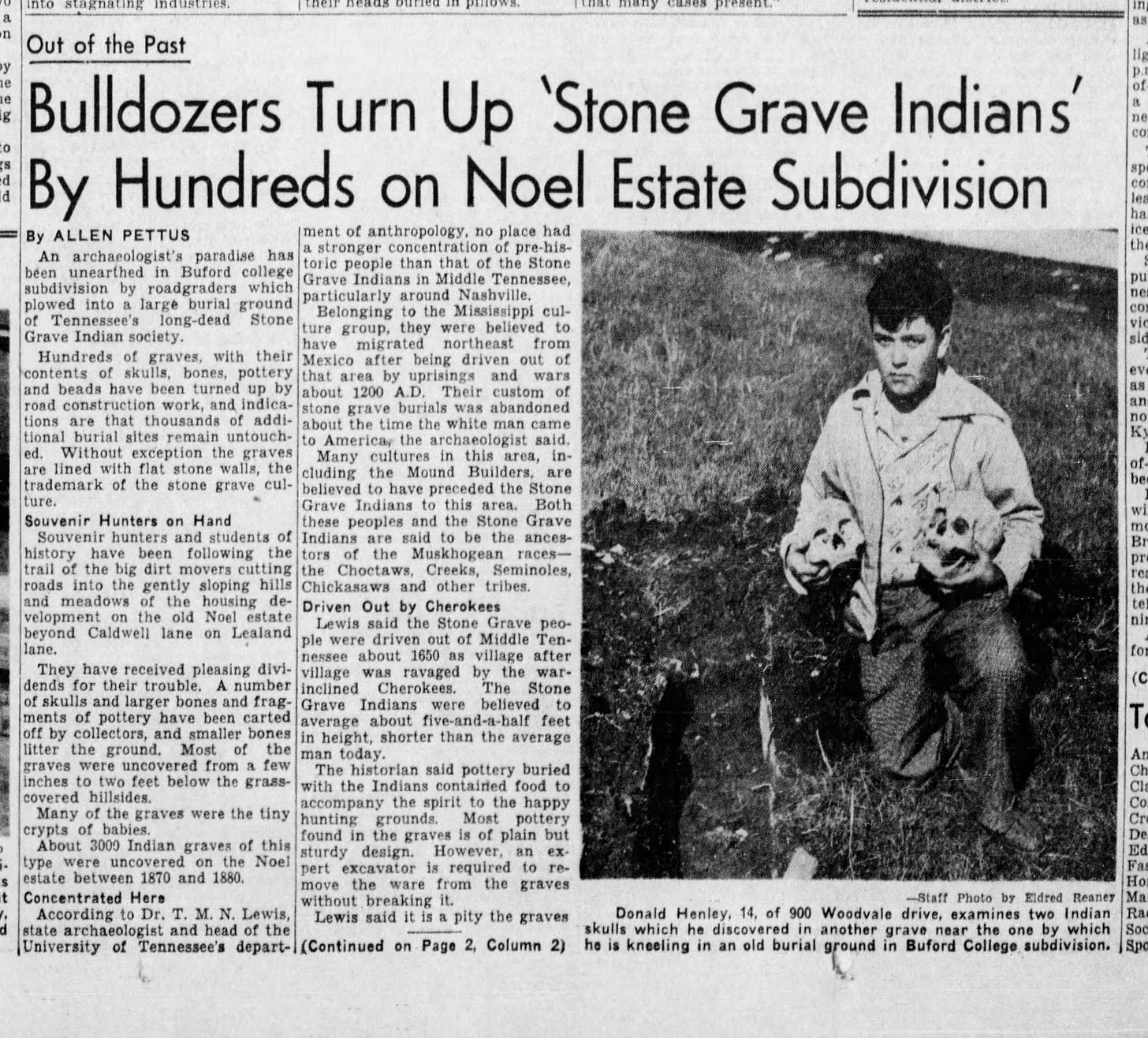

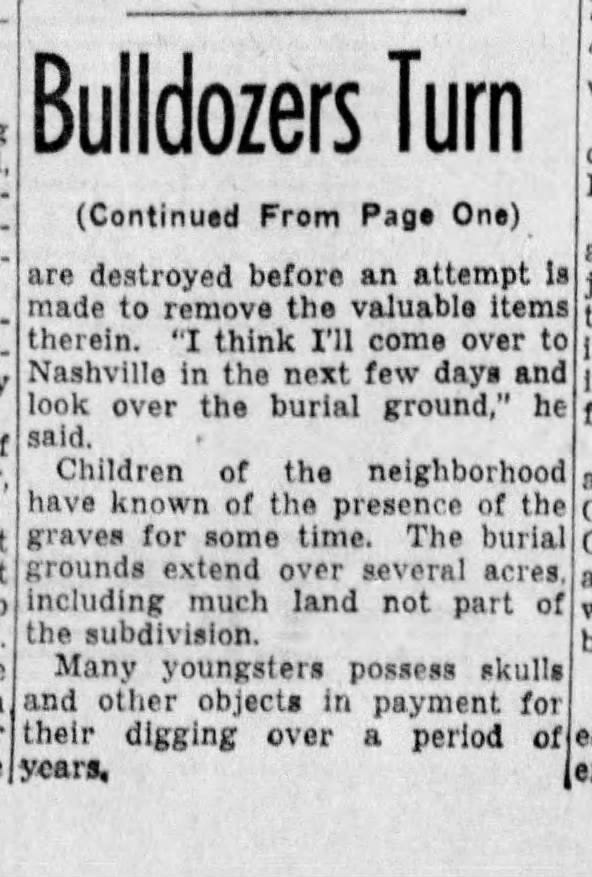

Since we’re talking about old newspaper photos from my neighborhood, I give you this gem from the Nashville Tennessean, March 12, 1949

The photo that accompanies this article is one of my favorites. Everything about it is funny and horrifying. Doubly funny if you know that Donald Caperton Henley is a childhood friend of Pat Boone, who also lived in this neighborhood and who also went to David Lipscomb High School and College at the same time as James Lee McDonough. Henley even wrote a couple of songs with Pat Boone in the 1950’s, most notably, Lipscomb University’s alma mater. (And, yes, Lipscomb University is my employer.)

Horrifying because 900 Woodvale, young Don’s childhood home, is only three blocks from my house. Which means that they were still turning up nearly complete skeletons in this neighborhood well into the the 20th century.

Doubly horrifying because of the callously disrespectful way Don is handling those skulls. Callous disrespect, of course, being a common theme in the exploitation of native burial grounds in both fact and fiction, although in fiction, such disrespect usually gets punished by angry spirits. Unfortunately, the story of the actual Noel Cemetery features no supernatural justice, just the depressingly common, thoroughly profitable looting of native graves.

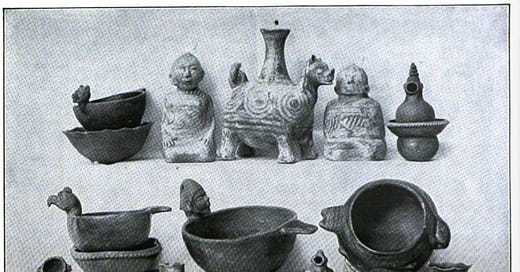

Anyone with even a passing interest in Nashville’s late prehistory has heard of “The Noel Cemetery,” immortalized by the two editions (1890, 1897) of The Antiquities of Tennessee by Gates P. Thruston. The excellence of the volume prompted the American Association for the Advancement of Science to elect him a fellow – something he considered the highest compliment every paid him. Thruston’s preface is dated June 1890 and begins with mention of “the large aboriginal cemetery near Nashville [that] was discovered and explored about two years ago.” That reference is to the enormous numbers of stone-box graves along Brown’s Creek on land then a farm of Oscar F. Noel. By Thruston’s estimate, about 4000 stone-box graves were dug during the four years between 1886 and 1890. While we can only hazard a guess as to how many were dug before and after, certainly it would not be outlandish to suggest a number as high as 8,000 graves. Thruston and the Noel Cemetery would further be immortalized by the preservation of the collection largely intact. Thruston donated it to Vanderbilt University in 1907, where it remained until 1982 when it was placed on permanent loan to the Tennessee State Museum.

General Thruston’s explorations were, by the standards of the day, rigorously scientific. Unfortunately, the same can’t be said for the many hundreds of amateurs who happily plundered stone-box graves all over this area. (Stone box graves are pretty much a Nashville thing. Very few have been found outside of Middle Tennessee.) The natives buried their dead with pottery and tools, which were eagerly sought out by modern Nashvillians and others. There are extensive collections of Nashville grave pots in universities and private homes all across the country, and archeologists are identifying looted items all the time.

This is such a fascinating topic that it’s a shame it’s so poorly known by the general public. My next door neighbor, an educated man who’s lived in the neighborhood for nearly 20 years, had never heard of the Noel Cemetery, and seemed surprised to learn he was living on a burial ground. But, such is the state of education in modern America, where we’re increasingly disconnected from our past.

I’ve got a lot more to say about the Noel Cemetery and the Mississippian culture in Nashville, but will save it for a later date. In the meantime, just let me say that I’m actually sort of sorry there wasn’t a grave in my basement.

Thanks for reading! If you’re not a subscriber, be sure to sure to sign up for twice-weekly updates sent directly into your email inbox.

An Eccentric Culinary History is pretty good description of the general content of this newsletter, eccentric pieces that reflect my odd and wide-ranging interests, primarily culinary and historical in nature. Take a look at the archives for a better sense of what you’ll get twice a week.

Thanks again for your attention and support, and I’ll see you on Monday with something new.

fascinating! sadly unsurprising that grave-robbing is so common in a society that has such contempt for the past.