I’ve just managed to work my way through the first three seasons of the big breakout hoo-haw melodrama The Chosen, a series somewhat sorta based on the New Testament story of Jesus and his Apostles. On the one hand, it’s excessively annoying, filled as it is with glaring anachronisms, clunky acting and near blasphemies. On the other hand, I feel somewhat compelled to watch it, mainly because the actor playing Jesus, Jonathan Roumie, is very good, and because, despite the idiocies, there’s something alive about this production.

Idiocies is a strong word, but hear me out. For some reason, writer/director Dallas Jenkins has decided that all of the actors portraying Jews must speak in the most phony-baloney “Aramaic” accent possible. It’s sort of Fiddler-on-the-Roof as filtered through a Los Angeles kombucha bar. Meanwhile, all the Roman characters speak the plainest, Midwestern American, a hilarious detail that implies the story is being told from the point of view of a random centurion. The silliness is laid on even thicker when we find that, at the court of Herod Antipas, the official Chuza and his Christian wife Joanna look and sound like patrician Yankees, John Cheever’s high WASPs in fancy dress, while the few Greek characters who wander on stage speak with British accents. The effect of this directorial decision is to emphasize the foreignness of Jesus and his runty followers. We viewers are outsiders, gentiles, looking on as these people with their funny accents enact their melodramas.

On the other hand, the costumes look great and the sets are quite handsome and atmospheric, although certainly too luxurious. The Apostle Simon, a humble fisherman—hammily played by the Israeli actor Shahar Isaac—lives in a lavishly appointed home, a multi-room Restoration Hardware townhouse with well-made furniture and lots of space. The problem here is that most moderns gravely underestimate the pervasiveness of poverty in the pre-modern world. In Ancient Rome, something like 90 percent of the population would have been near, at or below subsistence level, most of them earning what little bread they received as peasants working the land directly. Another 8 percent—some merchants, traders, a few artisans and officials—enjoyed a “moderate surplus”, leaving the vast majority of the resources for the remaining 2 percent, the elites. According to the historians Peter Garnsey and Richard Saller this was “the Roman system of inequality.” It’s also why economic matters figured so importantly in Jesus’s message, something The Chosen doesn’t really deal with, preferring instead to portray the Apostles as being drawn from the prosperous burghers of Galilee.

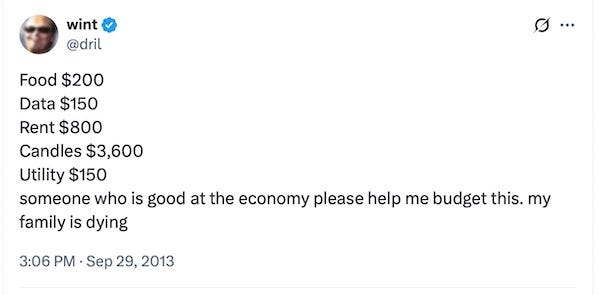

Aside from the furniture, one way this disregard for historical poverty shows up is in the domestic lighting budget. The Apostles burn candles like Jesus is made of money. It’s a small detail, but one that I find very annoying. In the first place, beeswax candles have always been relatively expensive. In the second place, 1st century Judaeans used almost nothing but small pottery lamps that burned olive oil. In fact, lamp fragments are one of the most commonly found things in Near Eastern archeological sites, and archeologists keep finding lamp workshops because lamps were such a common household article. This candle profligacy won’t register with most people, so I suppose this is a me problem, not a problem for the people who keep the Yankee Candle Store in business.

I don’t want to keep talking about The Chosen’s many historical inaccuracies and errors, not even its cockeyed, thoroughly modern view of gender roles, or literacy. I don’t want to do that because I want to get to what this production does right, and what it does right most of all is the actor Jonathan Roumie, the charismatic center of this production. Roumie has a handsomely sympathetic face with soft eyes and a sweet smile. As an actor, he so completely transcends the pedestrian writing that you find yourself wishing he’d been cast in a more competent production. Writer-director Dallas Jenkins has a tin-eared talent for clunky phraseology, best displayed in his version of The Sermon on the Mount, delivered at the beginning of Season 3. In the Bible, the Sermon on the Mount is an electrifying moment of divine instruction, rendered in The Chosen as a plodding series of Jesus’s greatest one-liners. “Consider the lilies of the field.” Yet, we don’t blame Roumie for the failure of the dialogue nor the silly accent. He’s too engaging and too sympathetic, his emotions seem too true. You can’t help but like him, even when the writers are doing him dirty.

Jenkins, however, does do a few things well dramatically. The first is that he delivers Jesus to us in small doses, keeping us in suspense and making Roumie’s on-screen time precious. Jesus is a mystery in The Chosen, and rightly so. And the mystery of Jesus, and why he chooses these 12 men to be his Apostles, is the motive power behind the series, not the small-stakes soap operas that are the lives of the Apostles. The second thing is that the miracles seem genuinely miraculous. Jenkins wisely choose to underplay them. No angelic music, or radiant light, just Jesus putting his hands on the afflicted and a few seconds later they realize they’re healed. It’s a shockingly effective and moving technique, one that brought me to the brink of tears a couple of times.

Of course, the real success of The Chosen has more to do with it being a soap opera than a true reflection of Jesus’s ministry. Jenkins’s smartest decision of all, from an entertainment standpoint, is inventing personalities and complicated backstories for the twelve Apostles. Instead of simple fishermen, tentmakers and reformed tax collectors, we get Matthew the autist, estranged from his parents, Thomas the caterer, hot to marry the headstrong Ramah, and Simon the reformed Zealot assassin with the crippled brother. These subplots provide grist for the Jenkins mill, soap opera complications that play out while we’re waiting for Jesus to do his thing. It’s emotionally manipulative and, as these things frequently are, addictive.

Ultimately, The Chosen is a near perfect reflection of American Christianity in the first half of the 21st century, blandly therapeutic and middle class. The Apostles are not desperate religious revolutionaries, fanatics following the Messiah, they’re your neighbors on the cul-de-sac with the same petty concerns and family complications. One of the most revealing subplots is when Zebedee, the father of James and John, decides to start an olive oil business to “support the ministry”. For those outside the current Evangelical zeitgeist, this is known colloquially as a “kingdom business” or “business-as-mission”, an American innovation that transforms business success into spiritual ministry, capitalism as a form of Christian witness. So, Jenkins succeeds completely in making the Apostles relatable to the average American mega-church-goer, but at the cost of both historical accuracy and spiritual truth. In doing so, he inverts the values of the New Testament, in which desperate men and women, sinners, sailors, thugs, and reformed prostitutes, living on the edge of starvation and death, upend the world with a message of salvation. Jenkins’s Apostles seem to risk little and gain less from the arrival of Jesus. Their lives are barely disturbed, which is pretty much the current American model of Christianity.

Thanks for reading! If you’re not a subscriber, be sure to sure to sign up for sort-of-weekly updates sent directly into your email inbox.

An Eccentric Culinary History is good description of the general content of this newsletter, pieces that reflect my odd and wide-ranging interests, primarily culinary and historical in nature. Take a look at the archives for a better sense of what you’ll get twice a week.

Literacy is not such a problem. Josephus in Against Appion says that all male Jews are literate.