In the first decades of the 20th century, if you lived west of the Rocky Mountains, one of the best bargains around was a bowl of cheap noodles, served up for a dime at a Chinese or Japanese “noodle joint”. Aside from the noodles, these establishments had other attractions. They stayed open late into the early morning hours, had private booths with doors that closed, and usually offered strong drink, louche entertainments and the possibility of lively company.

Why white men and women of refinement and of appearance indicating social superiority drift down Noodle alley may be explained in a brief sentence—thirst for adventure. They call it larking, sometimes slumming.

The Anaconda Standard, Anaconda, Montana, February 3, 1907.

Frequented by all levels of society, from parson to prostitute, noodle joints were places you went to eat cheap, drink late, and raise a ruckus, not necessarily all at the same time. A few were respectable, red-dragon-decor dining houses that, after the theaters let out and the bars closed, served cheap food and tea pots full of beer to young drunks, sometimes with live music. Others were second-floor dives, a grim room above a grocery store in Chinatown, where the food was dished up by waiters who spoke no English, but enforced order with a meat cleaver and bat. (“So authentic!”)

In the 20’s, they’d have been called speakeasys, but before the Great War were “blind pigs”, bootlegging liquor without a license and after hours. The moral crusade against strong drink was raging, and city fathers, pressed by city mothers, pushed the police to enforce laws that were probably better ignored. The old-time newspapers from Los Angeles to Seattle, east to Billings and Salt Lake City, were filled with raids and fines, wayward teens, fist fights and carefully shouted moral outrage. Some cities, like Ogden, Spokane, and Salem, Oregon, passed laws outlawing private boxes, limiting hours, and setting curfews for teenagers.

Most people, however, just loved those late-night noodles too much to care.

“Noodle fiends” were a recognizable phenomenon, and newspapermen waxed poetic in describing them.

There are fiends of many kinds. There is such a thing as a China noodle fiend. The noodle joint is visited nightly by many odd characters—people who eat noodles because they are Chinamen and have been brought up to make the ordinary meal of a bowl of noodles, people who eat noodles because they are close to being dead broke and want to fill the ever crying cavity as cheaply as possible, people who eat noodles because they know they have not seen Chinatown until they have eaten noodles in a China noodle joint, and people who eat noodles because to them a bowl of noodles is a banquet. Fresno’s Chinatown has noodle joints where go hoboes, negroes, train hands, policemen, clerks, newspapermen, men of many colors and standings in life. Women patrons are less frequent, but once in a while the sightseer from this side of the tracks goes over and indulges with great pride in a Chinatown noodle feast.

[…]

There are many reputable business men in Fresno who would walk from the Grand Central corner to Chinatown after a bowl of China noodles rather than accept an invitation into a downtown restaurant to eat a roast chicken.

~ “A Chinese Noodle Joint” The Fresno Morning Republican, November 6, 1904

So, let us stipulate that some of those noodles were excellent, addictively excellent, and that you and I would have been making the regular trek down Noodle Alley for a bowl or three.

Here’s another account:

Noodle eating is a habit. The habit generally begins through mere curiosity, an appetite for them is speedily developed and at last they become a passion.

No matter from what social set noodle lovers come, on the whole they form a peculiar, happy go lucky cult. Like stories told of the Chinese “hop” pipe, it seems unnatural for the “blues” to lurk in the house of steaming noodles.

~ The Spokane Press, February 20, 1910

Chinese noodles can cure you, cheer you, satisfy you better than the opium pipe. (Also, according to the authorities, available in many noodle joints.)

But, my question is, what kind of noodles did you get for your dime?

In 2022, when you tell me “Chinese noodles” or “Japanese noodles”, I know what to expect. But, what was actually served to those early 20th century noodle fiends?

Happily, a few descriptions have survived. For example, frequently mentioned as a constant in the Chinese noodle joints was chow mein, stir fried noodles with typical add-ins of meat, vegetables, mushrooms. But, chow mein, at 35 cents a plate, was more expensive than other, more delicate and reasonably priced preparations, noodle soups chief among them. Back to the Fresno Morning Republican in 1904…

The noodles are then placed in the bowl and a half a hard boiled egg, a piece of boiled chicken, and a piece of pork and beef placed on top. A small dish, about the size of a butter dish, is filled with a Chinese sauce flavor. This and the noodle bowl are carried out by the waiter and the two laid side by side before the noodle fiend.

The noodle fiend always uses the sauce. The sightseer and novice generally refuse to taste it. It is black and suggestive looking and the first thought is “Bugs.” As a matter of fact the sauce is as clean as the noodles. But every person to his taste. Noodles are noodles with or without sauce. The sauce lends flavor.

A simple noodle soup garnished with a hard boiled egg and pieces of meat? That sounds a lot like yang chun mian, (in Pinyin, yáng chūn miàn) or “plain noodle soup”, featuring a broth made from lard and soy sauce, a very cheap dish to make, but tasty nonetheless. This plain noodle soup is probably the basis of what came to be known in Chinese-American cuisine as yaka mein, or yat-ca-mein, or yock-a-min, derived from the Cantonese words for "one order of noodles”, what the waiter says to the cook. (Later, yaka mein is somehow, through the miracle of America, converted into a New Orleans hangover cure.)

At least, yang chun mian is what I suspect here. Cheap and good. Set me straight in the comments if you think I’m wrong.

But, now, what about those Japanese noodles? What would you get in a Japanese noodle joint in, say, 1910?

This was a little harder to track down, but I think I found it, and it’s what you’d expect.

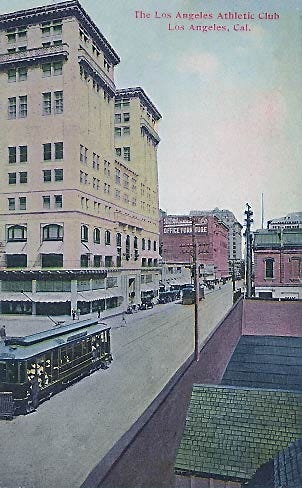

The writer here, in 1935, is Gilbert Brown, a Los Angeles theater and book critic of long standing. And twenty years earlier, in 1915, Harry’s noodle wagon would have been in front of the Los Angeles Athletic Club, an 8-story Beaux-arts building that opened for business in 1912.

Gilbert Brown, noodle fiend, is reminiscing about boiled noodles with a “thin, delicately-flavored sauce, a slice of mushroom, a hunk of deep-fried fish, a slab of bean cake and a handful of chopped onion tops sprinkled all over.”

Soba or udon? I’m betting udon in a dashi, or a miso-dashi broth. But, in truth, it could be either one.

I say this because Nipponese Harry was the owner of what was then known in Hawaii as a “saimin wagon”, a mobile noodle cart selling Japanese noodles (soba or udon) in a miso-dashi broth, topped with whatever local ingredients were available. Saimin wagons were ubiquitous in Honolulu before the Second World War. Of course, unless Harry had gone through Hawaii, which was not unusual for many Japanese immigrants, he would have probably called his food cart a yatai. But the principle was the same.

By the way, 7th and Olive was in downtown, several blocks outside of Little Tokyo. It would be an interesting exercise to see if we could track down early food cart culture in Los Angeles. It’s obviously not just hot dogs and tamales being served out on the streets.

Speaking of local ingredients, if you’ve read my two-part discussion of sushi in America, The Great Sushi Craze of 1905, you probably remember that there was a Japanese fishing village at the mouth of Santa Monica Canyon that shipped upwards of 30 tons of fish into LA every weekday. It also produced an American-made katsuobushi, the dried bonita flakes used in making dashi.

Of course, Harry’s late-night noodle wagon wasn’t, strictly speaking, a noodle joint. There were no private booths or tea pot beer. But, despite that, I feel safe in saying that if, in 1910, you’d asked for Japanese noodles in a Japanese noodle joint, you’d get udon or soba in a miso-dashi broth with some interesting and tasty things on top.

During the first two decades of the century, the noodle joint boom was a sort of gold rush in the western half of the United States, and fortunes were made catering to America’s new found love of Asian noodles. Chinese restaurants (although not Japanese restaurants) soon sprang up all across the country. In the east, however, it was chop suey, not noodles, that filled the seats.

The old noodle joints eventually ran out of steam. Women’s suffrage, Prohibition, World War I, and an increasing antagonism toward Asian immigrants led to crack downs on drinking and vice, making noodle joints much less profitable. Women voters cleaned up a lot of towns in the twenties. You could still get your Chinese or Japanese noodles, but it would be in respectable restaurants run by family men, who were in America for the long haul.

Thanks for reading this! Leave a comment, follow me on twitter, like the facebook and share this article.

See you on Monday!

Love this. Here's a related short documentary about Santa Barbara's Chinatown