Few things are more distressing or funny than watching a fat man labor up a steep hill. And at the end of February 2015, at the height of the Chilean summer, when temperatures in Santiago were in the mid-90s, I was that fat man.

I was dragging myself up Cerro San Cristobal, the steep hill with the statue of the Virgin Mary on top, because I had foolishly agreed to accompany two dozen 19-year-olds to Torres del Paine, a trip that would include, I had been told, an 18-mile hike into the mountains of Patagonia. I was thus preparing myself by taking long daily walks—five or more miles—through Santiago, walks punctuated by stops at various picadas and fuentes de soda for nourishment and refreshment, usually in the form of a lomito italiano and a fanschopp or three.

I was trudging up Cerro San Cristobal because I had at last concluded that long sidewalk strolls in the flatlands of Santiago were insufficient preparation for mountain climbing. And, so there I was, mid-morning, two-thirds of the way up the hill, out-of-breath, red-faced and sweating like a prize sow, and the worst part was, that I was not alone. Cerro San Cristobal was packed with bikers, walkers, picnickers, and tourists, and because of that, I was being repeatedly accosted.

“Sir. Are you okay,” asked a park volunteer in a green vest, “Do you need help? A drink of water?” He held out a plastic bottle.

“No, I’m fine. Thank you.”

Two hundred paces up the hill…

“Do you need assistance, Sir,” said a young woman with a clipboard, “there’s a bench right there.”

I waved her off with a grunt.

Another three minutes trudge and a pair of Carabineros in a patrol car slowed to crawl next to me, both of them gawping. Just when I was sure they were going to ask if I needed a ride to the hospital, the one in the passenger seat pointed to the front and they accelerated away. I suspect they thought I was going to die, and were worried they would have to lift my body into the ambulance.

My biggest mistake was thinking there would be a motero, someone selling mote con huesillos every few hundred meters on the way up Cerro San Cristobal . I had not brought along any water. My entire rehydration plan was based on mote con huesillos. I expected that, like everywhere else in Santiago, mote con huesillos would be available for purchase from a cart at frequent intervals.

I was wrong.

Mote con huesillo is one of those things that doesn’t knock you out, so much as sneak up on your blindside and grab you in a bear hug.

When you first encounter mote con huesillos, on your first trip to Chile, you don’t think you will like it, but you order it anyway because everyone around you has one in their hands. And when you try it, you notice the intense sweetness, but not much else. Yet, by the end of the second week, you’ve ordered it several times and can’t stop thinking about it, hoping you’ll have have another one soon.

Mote con huesillo is the most peculiar libation since bubble tea. It’s a sweet syrup of caramelized sugar water, served ice cold, with a pair of rehydrated dried peaches and a fistful of mote, wheat slow-cooked in an alkaline solution, i.e. nixtamalized.

It sounds like something concocted by German naturists as a breakfast food, except it’s sweeter than honey, more filling than spatzel, and more refreshing than anything found in Germany that isn’t served in a festive, one-liter stein.

As the advertisement says, mote con huesillo is the “drink of Chile”, a fact that may be disputed by the patrons of the pisco sour, but not by me, and not by hundreds of thousands of Santiagueños who support a motero on every corner. “More Chilean than mote con huesillos,” is a popular saying, the equivalent of “more American than apple pie,” and liking it is the ultimate test of chilenidad, of Chileanness.

The story of how mote con huesillos found its way into the Chilean diet starts, as do so many of these stories, with the Mapuche, the native people who held off the Spanish and remained independent of colonial control for nearly 300 years.

As I said in my last piece, the Mapuche were one of the few New World peoples who readily adopted Old World crops. In 1544, Pedro Valdivia, the Spanish conquistador who founded Santiago, distributed a large amount of wheat seed to the caciques of the Mapuche, as part of the effort to pacify and civilize the natives. The Mapuche planted it and loved it. Wheat grew especially well in the soil and climate of the Mapuche territory, and added a dimension of flavor and food security to the Mapuche diets. It provided enough extra food that it actually enabled the Mapuche to better resist the Spanish. So, it is with some justification that the Chilean historian José Bengoa calls the Mapuche “la gente del trigo“, the “Wheat People”, which as far as it goes is a half-accurate description of a badass people who came very close to defeating the Spanish.

Oddly, although wheat became a major staple in the Mapuche diet, it was not usually served in the form of bread. That came later, in the late-17th century, likely introduced by Spanish and creole women who had been captured by the Mapuche.

One famous example of such a captive is Isabel Vivar y Castro who was captured in 1633 and made the wife of the Mapuche cacique Curivilú. Two years later, she gave birth to his son, Alejandro. A few years after that, Isabel and Alejo were “rescued” by the Spanish and taken back to Concepción, where Isabel was ostracized for having been the wife of an indio, and Alejo for being a mestizo. Her response was to become a nun, and to give the boy to the Franciscans to raise. Alejo grew to adulthood, joined the Spanish army as an arquebusier, was denied promotion because he was a mestizo and deserted, returning home to his father. Once back in Araucanía, Alejo became an important war chief, a toqui. He introduced up-to-date Spanish military techniques and lead an army that destroyed Spanish forts and massacred settlements. In 1660 he was killed by his two native wives for getting drunk after a victory and raping a captive Spanish woman. (Chilean history, largely unknown, is wild.)

So, bread arrived late and was first enjoyed by the chiefs, who were most likely to have captive white women around the camp. Early European and Chilean visitors, both voluntary and involuntary, rarely mentioned bread in their accounts of Mapuche meals until the 18th century. Instead of bread, the Mapuche enjoyed their wheat as mürke, or mulke (in Spanish, harina tostada), toasted wheat ground into a coarse flour and then made into a gruel called ulpo, which is mixed with any variety of liquid, from honey to milk to water to jam, and served hot or cold.

Today, harina tostada makes its appearance in some odd places. Chileans like to sprinkle it onto watermelon as a condiment. They add a tablespoon or two of toasted wheat to cold water as a summer beverage, or into beer or wine as part of a native cocktail called the chuplica. It’s also added to stews as a thickener, served with sugar as a candy, or with fried onions as a snack. There's even a toasted wheat ice cream.

The way the Mapuche prepared wheat was the same way they prepared maize: toasted over a fire and milled on a stone mortar with a stone pestle. And, if you’re toasting wheat the same way you’re toasting corn, why not also slow-cook whole kernels of wheat in a pot filled with wood ashes? Although, wheat flour, unlike plain corn meal, has no trouble making a dough, nor is it deficient in niacin or protein. But, if you nixtamalize wheat the result is mote, a plump bit of chewy goodness, not unlike pearled barley or bulgar wheat. It can be added to stews and soups to provide more body and extend the dish cheaply, or mixed with green beans as porotos con mote, or with potatoes in papas con mote.

By the 19th century, moteros, the sellers of mote, were a fixture in Santiago, with a large number of them congregating in the Barrio Mapocho around the Cal y Canto bridge, near the present-day Mercado Central. There, near the river, they had ready access to water, a necessity as the production of mote required a great deal of it. Their technique for processing wheat into mote would have been exactly the same as shown in the video below (except for the plastic buckets), where Señora Herminda Diaz Riquelme of Los Sauces in the Araucanía Region (old Mapuche territory) makes artisanal mote in the old fashioned way.

At 0:43, you can see Sra. Diaz R. sifting wood ashes, the key ingredient in the alkaline solution that nixtamalizes the wheat. The last half of the video is devoted to the extensive washing of the mote.

Another major agricultural product of colonial Chile was dried peaches, huesillos, which were mentioned in various sources as early as the 17th century, and were one of the items regularly exported to the more opulent colonial city of Lima, Peru.

The real conundrum for food historians of Chile is when mote met huesillos, the Chilean version of who got chocolate in my peanut butter. The best guess is that mote con huesillos was something cooked up in the late 19th century, in Santiago, as a summertime refreshment for city dwellers. If your Spanish is decent, there’s a good consideration of the problem at the blog Urbatorium. If your Spanish isn’t, then go read Eating Chilean written by a retired American professor of anthropology.

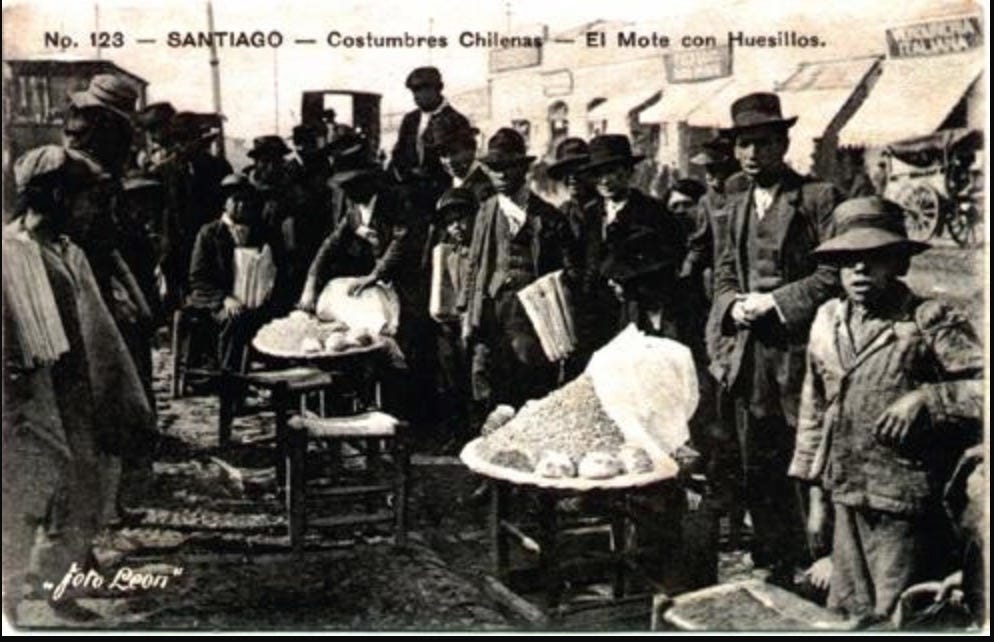

However it got together, by the second decade of the 20th century, mote con huesillos was well established, as evidenced by this postcard from 1915:

That gawping look on the faces of the boy and the man on the far right of the photo, that’s exactly how the Carabineros looked at me as I trudged to the top of Cerro San Cristobal, as a curiosity that might turn into something unpleasant and dangerous.

It was my fault I hadn’t brought any water on my hike up San Cristobal. I thought it likely that there would be moteros all along the way, dispensing their sugary Balm of Gilead to the needy. But also because the best place in the world to have a mote con huesillos is at the top of Cerro San Cristobal.

In my mind, Cerro San Cristobal and mote con huesillos go together like dried peaches and nixtamalized wheat.

At the top of San Cristobal, after you get off the funicular, but before you head up the flight of stairs to the base of the Virgin Mary statue, there is a patio with a half dozen stands selling souvenirs, snacks, drinks, and mote con huesillos. Buy a mote con huesillos, go to the edge of the patio, sit on the wall, and gaze at the city spread out beneath you. It’s a view that will reward you many times over, and a mote con huesillos is the best thing to drink while you look at it.

But, whatever else you do, take the funicular up to the top of Cerro San Cristobal. Please, take the funicular!

Follow me on Twitter, like me on facebook, and recommend me to your friends. See you on Thursday!

HD, I don’t understand how you don’t have more likes and comments. Your writing, research, and storytelling are simply magnificent. Thank you so much. It is so wonderful to read something so enriching and that is not about another third rail political or culture war hydra.

I enjoy your stories very much.It is a pleasure to read something not political and not "polarizing". You have taught me a lesson. My blog www.bonniebmatheson.com often gets passionate about things in the news. But I get many more comments on and off the blog for the articles that are just good stories. Because of you I think I will stick to the "stories" in the future.

Your writing and subject matter is so refreshing. It is like a cool drink on a hot day in the manner of 'Mote con Huesillos'. I subscribed after reading about the Abernathy Boys, but it was a free subscription. NOW, I am going to resubscribe and pay money! this is worth it.