In my ancient and medieval history courses we always spend some time talking about the physicality of the pre-modern world, and how, until the industrial age, long days of hard physical labor were the norm for the vast majority of people. Because of this, we can say the following about the people of the pre-modern world:

1) their average level of physical fitness was much, much higher than ours;

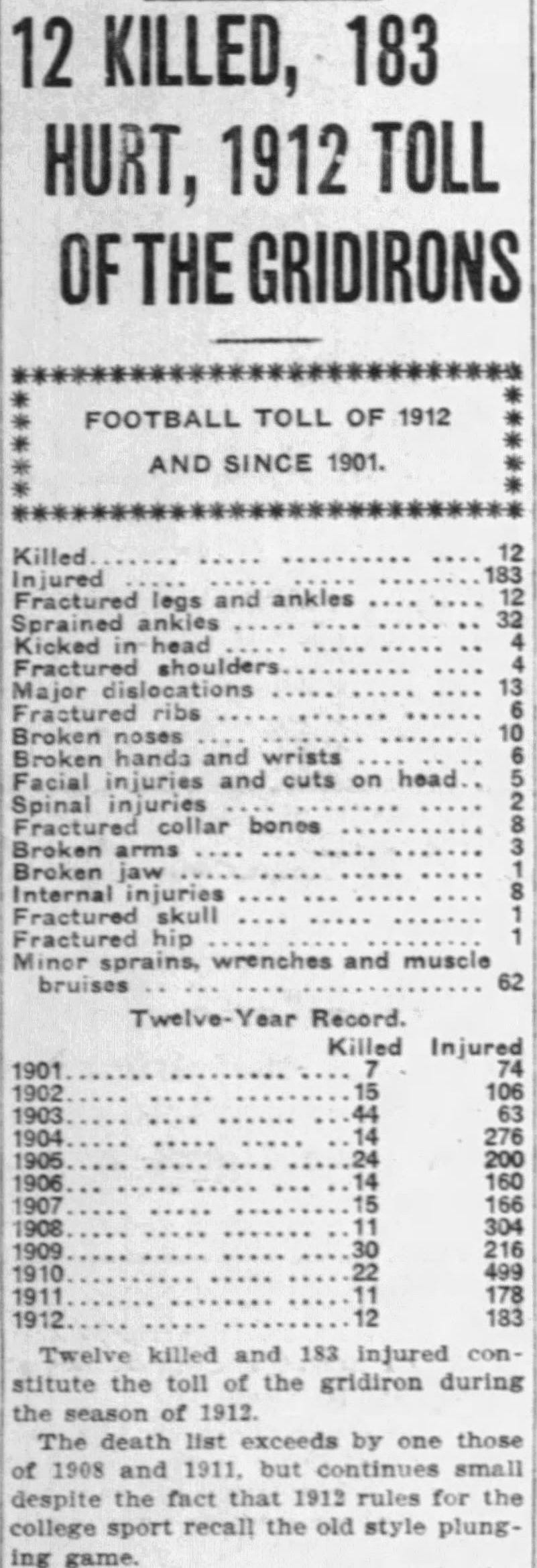

2) there was a wide prevalence of what we think of as "sports injuries" (ACL tears, shoulder injuries, etc) that could not be treated because of the rudimentary state of medicine;

3) people’s bodies reflected their professions. (“The smith, a mighty man is he, with large and sinewy hands…”)

There are all sorts of fun evidence you can bring out to prove these assertions, for example, how it’s possible to identify the skeletons of medieval English bowmen by their peculiar asymmetry (os acromiale in the right scapula, left humerus longer than right, etc). My current favorite data point, however, is a recent study that showed that the average European woman, from the Bronze Age to the Middle Ages, had the sort of upper-body bone density that is found today only among elite women rowers. In other words, for 5,000 years, European women were "stronk like ox”.

I bring this up, because this discussion of pre-modern physicality often leads to talking about modern elite athletes and how their bodies reflect their sports, such as strangely-shaped swimmers and lop-sided tennis players, who, like medieval archers, are often afflicted with os acromiale. This usually ends with me talking about how much bigger football players are than they were just 40 years ago. Most of the 19-years-olds I teach, however, refuse to believe me when I tell them that National Championships were won, within my lifetime, by teams with average weights below 200 lbs.

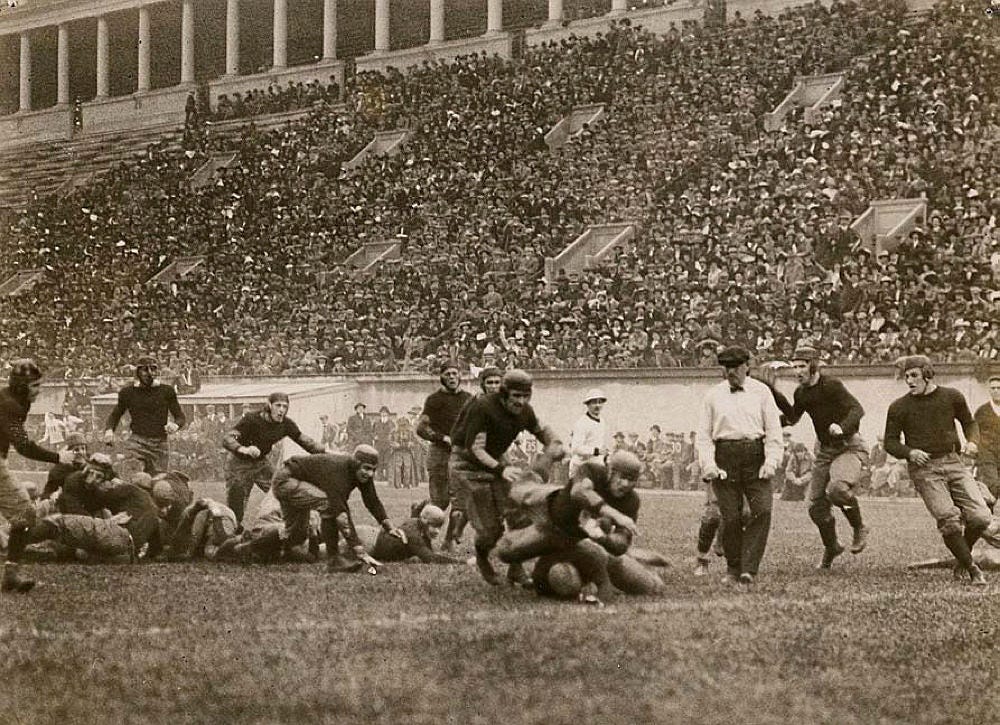

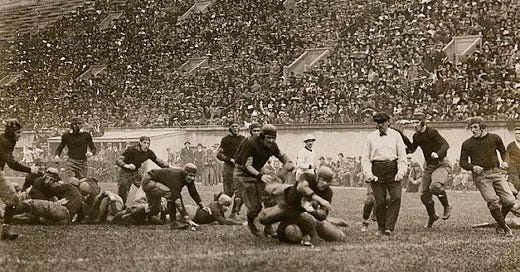

The small size of old-time college football players is easy to see in one of the Ur texts of the game, Owen Johnson’s 1912 novel, Stover at Yale. There we find that Dink Stover, the hero of the book, and starting end of the Yale eleven, weighed a whopping 141 pounds. Although, admittedly, Dink, a ferocious tackler, was ashamed that he hadn’t reached the more respectable football weight of 150 pounds.

But that was a century ago, when football was played by tiny men who were much less physical than today’s giants.

To prove my point using more recent data, I went down a rabbit hole looking up the size of historic college football players. Luckily, HuskerMax.com, an obsessive fan site devoted to the Nebraska Cornhuskers, has put more than a century’s worth of rosters online. This is serendipitous because I remember, in 1983, my father talking about how Dave Rimington, the Nebraska center, was a “freak” because he was 6’3” and 290 pounds. (My father was a big Penn State fan, and their 1983 season started very wrong because of Rimington and friends.)

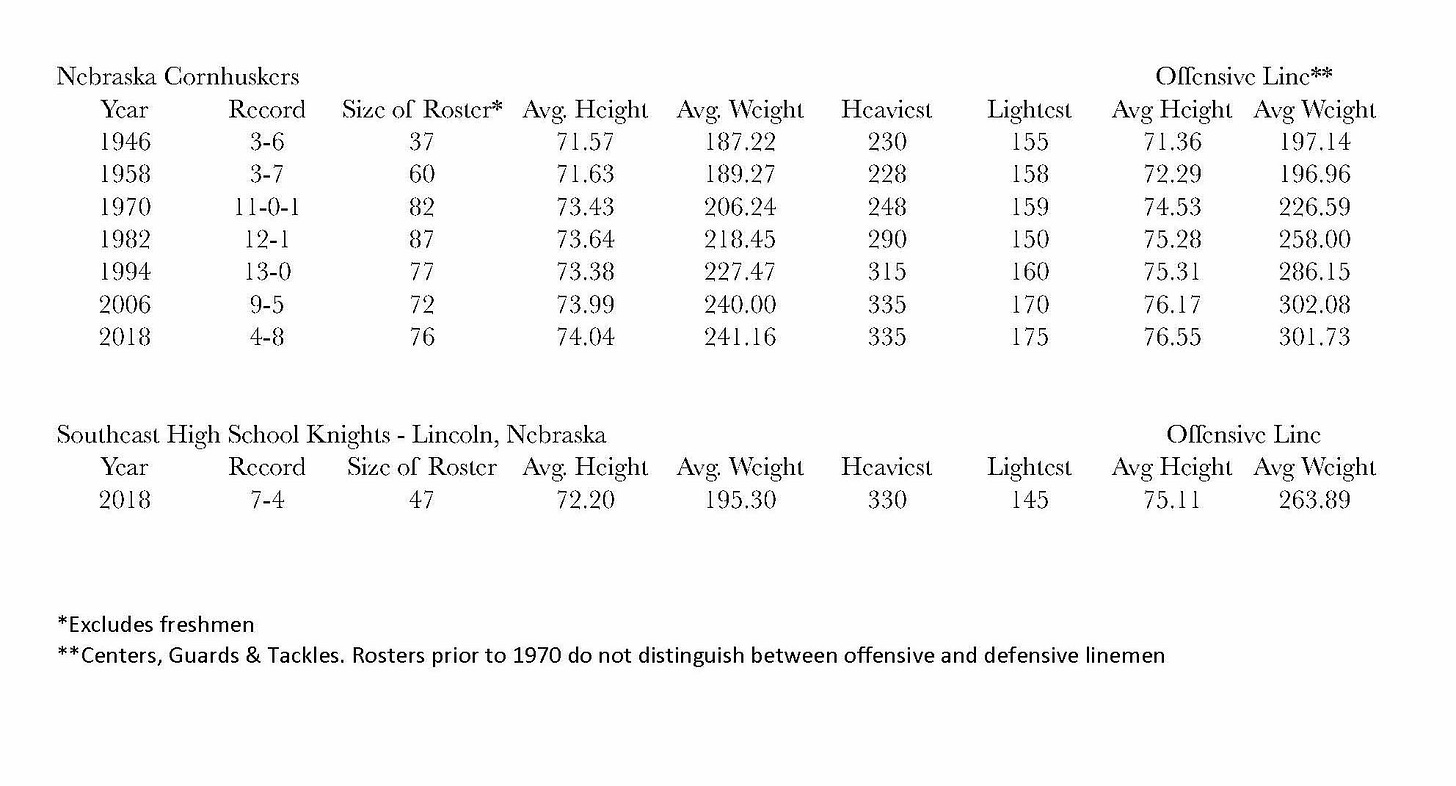

So, I went and looked at the rosters of seven historic Cornhusker teams, starting from 1946 and spaced 12 years apart. I did this because the 1970, 1982, and 1994 teams were all National Champions, historic teams that completely dominated their opponents.

As you can see, these numbers speak for themselves…

The weight of an average Cornhusker went from 187 pounds in 1946 to 241 pounds in 2018, an increase of 54 pounds. While the average Nebraska offensive linemen gained almost 105 pounds and 5” in height!

More amusing, I’ve included, for comparison’s sake, a recent high school team from Lincoln, Nebraska. The 2018 offensive line at Southeast High is almost 6 pounds heavier, on average, than the offensive line of the 1982 National Champions, a line that included two future professionals (Dean Steinkuhler, 257 lbs. and Dave Rimington, 290 lbs.) and two All-Big Eight selections (Mike Mandelko, 256 lbs. and Randy Theiss, 255 lbs.)

Dang, even high school football players got big.

So, the question is why? Why did football players get so big starting in the late 1970’s and accelerating into the early 2000’s?

The main reason for the increase is an NCAA rule change at the end of 1964 that allowed for unlimited substitutions. This change resulted in the current “two-platoon system”, with a defensive squad and an offensive squad, special teams and lots of players running in and out. Prior to that (except for a few years around WWII), players removed from a game couldn’t return until the next quarter. So, leave in the middle of the second quarter, come back at the beginning of the third. In other words, until the 1960’s, the best players never left the field, playing offense, defense, kickoffs, extra points and returns, without rest. Say what you will, but 300-pound men are not noted for their stamina.

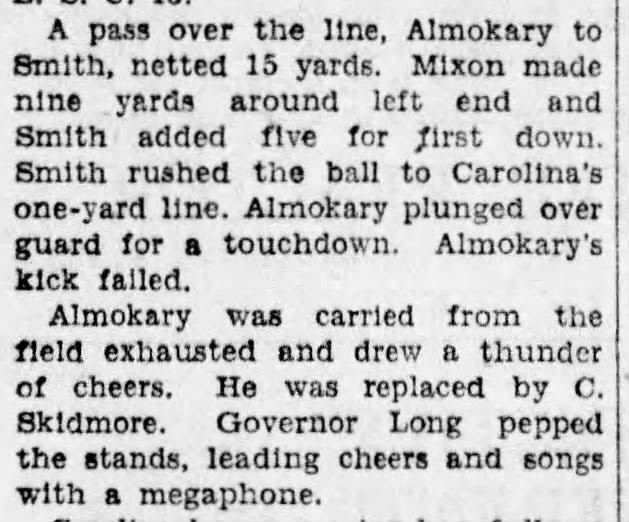

Dink Stover might have been a flyweight, but he played on both sides of the ball, blocking and tackling for as long as he could manage. Back in the day, Football was as much a test of endurance as it was of strength, and players being carried off the field after collapsing from exhaustion was surprisingly common.

With unlimited substitution came the era of big rosters and highly-specialized players. Linemen got bigger, wide receivers got faster, and kickers and quarterbacks got much, much better. This past season, Nebraska listed 152 players on their roster, including 19 players 6’6” or taller. Fredrick the Great would be jealous.

The NFL, which went to free substitution after 1949, has a very good discussion of the en-whoppening phenomenon at their website, broken down position-by-position, a discussion which contains this illustrative quote.

As data journalist Noah Veltman noted after crunching the numbers on NFL player height and weight over time, “nowadays, if you’re 6 foot 3 inches and 280 pounds, you’re too big for most skill positions and too small to play line.”

Pity the man who is a mere 6’2”

The other reason for the Age of Whoppers is because of the out-sized rewards now available in professional sports. Until the late 1970’s, most professional football players were part-time workers, forced to eke out a living working in factories or, like Terry Bradshaw, selling used cars during the off-season. Even as late as 1982, the league minimum salary was just $22,000, at a time when the median American family income was $23,433. In 2022, the NFL league minimum for a rookie will be $705,000, about ten times more than the median family income.

These potential windfalls are a powerful incentive for big boys and their families. As a result, sophisticated training starts early, in junior high, with summer camps, weight-lifting and nutrition programs (supervised feasting) and continues all the way to college.

For coaches, you can’t teach height, but if you’re a college coach making the big money, you can beat the bushes to find your Potsdam Giants, bring them to campus and fatten them up. The result might be someone like Mekhi Becton…

A 6’7”, 364-pound, 22-year-old behemoth, who was drafted in the first round by the NY Jets and given an $18.4 million contract. That’s a lot of money for being really big and really athletic. Unfortunately, Becton might actually be too big for the NFL. He missed most of his second season with a knee injury and, as part of his rehabilitation, the Jets want him to slim down to a more reasonable 350 pounds.

Personally, I’d like to see everyone go back to one-platoon football, with two-way players fighting it out on both offense and defense. But, such commonsense ideas are too far outside the maximalist urges of our present age.

Follow me on twitter, like the facebook, subscribe to the newsletter. Twice a week via email!

It would be interesting to compare these numbers with those of British pro rugby players over the years. While rugby players do have assigned roles anyone can wind up carrying the ball at anytime.

"Eke" not "eek", I hope.