Authenticity is overrated. I say this as someone who has gone to great lengths to find a bowl of real Peruvian tripe soup in a South American market. Culinary authenticity is not just overrated, it doesn’t exist in the 21st century. It’s a myth. Everything is connected and interrelated now. Everything is jumbled up, nothing exists in isolation. Everyone has a cellphone now. There are no more hidden food traditions waiting to be discovered; no more ancient grannies in jungle huts who’ve never seen a cookbook or a bag of MSG. The most remote places in the world have been brought into the clear light of TikTok. Anthony Bourdain ate warthog anus with Kalahari bushmen nearly 20 years ago.

I bring this up because last month I went home to Northern California for the first time in six years, and one of the only things I could think about was eating a tostada at La Hacienda, an old-school Mexican restaurant, a place that would be dismissed as too Americanized by online hipsters.

Chico is a small city 90 miles north of Sacramento in the Central Valley, a place that’s had the same relaxed hippyish vibe for the past 50 years. La Hacienda is the oldest restaurant in Chico, founded in 1948 by Nate and Tomasa Ybañez, who, according to a 1977 advertisement, “brought old family recipes to Chico and soon became known for their authentic Mexican cuisine”; family recipes brought from Fresno, it should be noted.

The tostada itself is impressively large and delightful, a crispy, plate-sized corn tortilla mounded over with beans, shredded iceberg lettuce, red onion rings, cheddar cheese, and slices of tomato and avocado, all of it very fresh. Your only decision when ordering is chicken, beef, pork or more beans. This is not a spicy dish. The meat carries what spice there is, a subtle undercurrent of chiles and cumin. I have historically wavered between chicken and pork, both of them very tasty.

What sets the dish and La Hacienda apart is the secret sauce, a sweet, very sweet, addictively delicious pink dressing served in a squeeze bottle. Back when Sunset Magazine was dispensing West Coast cool to the world, the Ybañez family refused to disclose the recipe to them at any price. Today, it’s only known by two people, who guard it like the crown jewels. Online spoilsports suggest it’s just honey, mayo, red wine vinegar, garlic and cumin. I’m dubious. The flavor seems more complex than that. It’s certainly more addictive than those ingredients suggest.

You’ll note, in the photo above, that there’s a single black olive nestled among the onions, which brings me back to that original discussion of authenticity and whatever that means. That black olive is a clue that this might be more than an Americanized knock-off of a muy autentico Mexican dish, that this tostada might be its own thing with its own noble history.

Black olives aren’t just that garnish your great aunt trots out at Thanksgiving, they’re a marker of Californio cuisine, of a distinctly California version of Spanish-Mexican food that developed in the 19th century. Here’s the writer Georgia Freeman describing it in her piece The Secrets of California’s Oldest Recipes

Marianne began cooking from these recipes four decades ago, when she married Jim Poett, a seventh-generation cattle rancher, and moved with him to the family’s 181-year-old ranch near Santa Barbara, on California’s Central Coast. The notebook was a trove of family history, as told through the recipes that the women of the family were eating and cooking in the ranch’s early years. And Marianne found that many of them have an important ingredient in common: black olives. “Olives are the sign of a California-style recipe,” Marianne explains to me as she juggles a variety of jobs, taking phone calls from the local newspaper (where she is the editor), improvising a recipe for tomatillo salsa, and arranging homegrown flowers in cans to decorate the table for the feast she is cooking for the two dozen friends and neighbors who are on the ranch to help brand the family’s cattle today. “If you see olives in a recipe for enchiladas or tamales, you know it’s from here.”

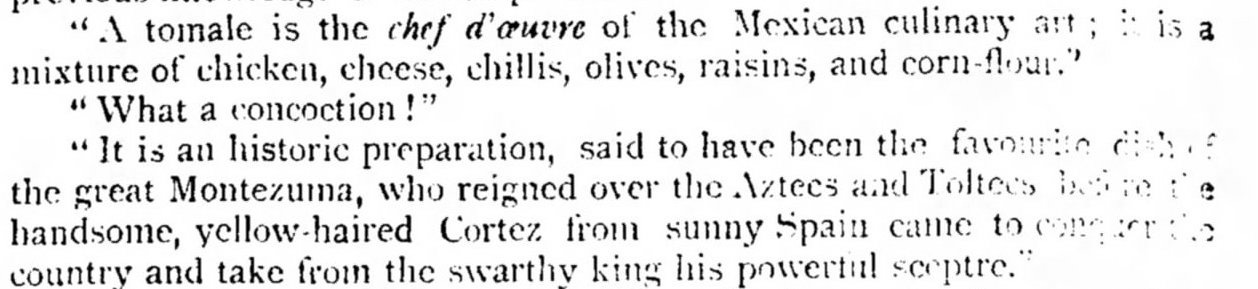

And if you need further proof of the importance of olives in Californio cuisine, here’s an excerpt from an English newspaper, The Pall Mall Gazette, January 15, 1894.

Note that the location, here, is Santa Barbara, California, where a tamale is a “mixture of chicken, cheese, chillis, olives, raisin and corn-flour,” a combination that would be impossible to find in Mexico City. Same for an enchilada, which the same author describes as being made of “layers of chillis, olives and cold meat well mixed with pepper sauce” and rolled up like a “French pancake.”

What confuses people obsessed with authenticity is that olives do not play much of a role in Mexican food in Mexico, where for a variety of reasons, some cultural, some climatological, they aren’t much seen. But, in California, 250 years ago, when Father Serra established the missions he immediately planted grapes and olives, both of which flourished in a climate that was closer to Spanish than Mexican. Which is why olives and raisins were in those tamales in Santa Barbara.

This means that generations of oven-baked chicken enchiladas, cooked up in Omaha and Oklahoma City, and garnished with sliced black olives from California, are more authentic than tacos al pastor cooked on a shawarma trompo, something that only arrived in Mexico in the 1930s.

See what I mean about authenticity being a crock? Culture is too polymorphous and mutable to pin down with a blunt term like “authenticity”. You can’t bludgeon a living cuisine into your square hole with prescriptive rules about what is and isn’t “authentic”. Things get away from you, and take on a life of their own, out-racing you and out-living your needless ire.

As a historian of food and culture, I care about the truth and about trying to untangle the Gordian knot of influence and counter-influence. As an eater of some repute, I care about taste. I don’t care much about authenticity. It’s too much of a slippery eel to get my hands around. All I can tell you is that the tostada at La Hacienda is delicious, something proven by the generations of diners who’ve kept that place in business. I can also speculate, with some justification, that that tostada, with that single black olive, is the remnant of an older food tradition, of a very old California way of cooking lying just out of view, hidden by our mania for the “real”.

P.S. I’m almost positive there were a lot more black olives on the La Hacienda tostada 40 years ago, when I first had one, but I’m not sure if that’s a real memory or not. What I am sure of, however, is that I’ve got a lot more to say about the topic of Mexican food in America and the role of California in its dissemination, but I’ve got more work to do before I spring that on you. In the meantime, if you haven’t subscribed, please do so. Also, hit me up on Twitter. See you next week!

P.P.S Georgia Freeman’s substack, The California Table has a lot of great recipes from the Golden State.

This was a treat to read! I'm a native (but not Native) Californian myself with a fondness for those Californio-style dishes. And your mention of Corning — and olives — reminded me that it's been too long since I paid a visit to The Olive Pit, right off I-5. They sell a lot of olives, of course, and also the best milkshakes I've ever had, which you can get with a shot of balsamic vinegar, which sounds awful but is delicious.

Thank you for writing this! I completely agree authenticity is overrated. Mexican cuisine took on so many cross cultural influences with ingredients that didn't exist there before colonization. (Cilantro, I'm looking at you, just to start with.) So, how far back do we go for something to be truly authentic. Can't wait to read your next article.