No, I am not the fattest man in Tennessee. I know this conclusively because I have recently been in a Super Wal-Mart in Mufreesboro. More surprising to me, however, is that even 160 years ago, I wouldn’t have been the fattest man in Tennessee, probably just in the top ten. In 1857, the fattest man in Tennessee was Sam Riddleburger, a popular Nashville restauranteur who weighed a whopping 543 3/4 pounds.

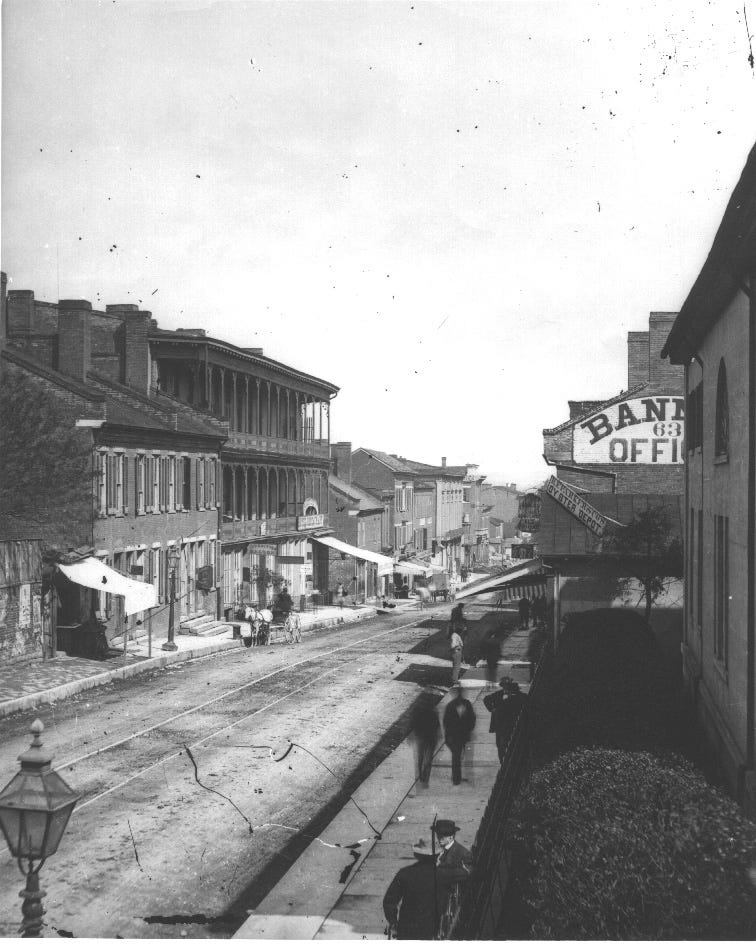

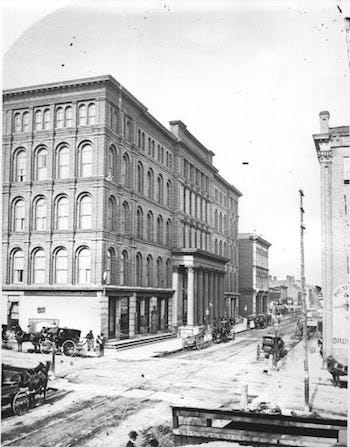

Riddleburger cut an imposing figure in pre-Civil War Nashville, a well-liked stout man with a knack for getting up elaborate dinners featuring the manly staples of the era, wild game, abundant Norfolk oysters, whiskey and cigars. Born around 1824, he started out as a Nashville postal clerk in the late 1830s as a young man of “comparatively slender build”. He clerked on steamboats — making the run to New Orleans and back — then owned a “billiard room, bowling alley and saloon,” and managed the race track, where his talent as a “getter upper of good dinners” became apparent. Sometime before 1856 he opened Riddleburger’s Eating Saloon in the Colonnade Building, just a block west from the Public Square on the corner of Deaderick and Cherry Street (the latter renamed 4th Avenue in 1906).

Sam Riddleburger and his brother John were what was known in the latter half of the 19th century as “sports”, dapper men who loved the demimonde and the louche entertainments that dwelled there. For the 25 years before his death in January of 1877, Sam was a regular in all the exciting and expected places: horse races, cockfights, illegal boxing matches and public hangings.

Both brothers were, “well educated and well bred.” John was “quiet, unassuming and courteous;” Sam, a bit more boisterous. Everyone who met them liked them. During the Civil War, brother John moved to Louisville and set up shop running “the biggest faro bank” in several states, accumulating over $100,000 in gold in the process. He bought racehorses and regularly took them to Saratoga, where the New York swells held court during the racing season.

If John was a man who loved cards and horses, Sam was the king of the fighting cocks, described by the Nashville Union and American, March 20, 1875, as “the most widely known game chicken raiser in Tennessee.”

Mr. Riddleburger has hundreds of his game stock scattered through Wilson county. They require to be separated on account of their belligerent propensity and consequently inhabit various farm-yards. We understand a Louisvillian won $250 on one of the Riddleburger chickens a few nights ago.

Sam popped up in the press with a surprising regularity. Here are two of my favorite mentions, the first from the Louisville Courier, May 29, 1868, from an account of a boxing match in Cold Springs Station, Indiana, that failed to go off.

The drenching showers of rain played havoc with all who wore linen coats, and there were many of them. We noticed many prominent Cinncinatians and Louisvillians present. We conversed with several who had come all the way from New Orleans–among them W. D. Davis–who had come to see the fight. We also met several from Nashville under the charge of a “heavyweight” named Riddleburger, who would easily balance 450 in the scales.

Imagine if you will a couple thousand sports in an empty pasture in Southern Indiana, many of whom traveled hundreds of miles hoping to see an “American Heavyweight Championship”, only to be thwarted when the police arrested one of the boxers. In the half-decade after the Civil War, manly fun was a precious commodity, often in short supply and eagerly sought out.

Happily, there were other forms of entertainment that we moderns lack. Here’s my other favorite mention of Sam Riddleburger, this time from the Nashville Union and American, August 5, 1869.

Sam Riddleburger, the largest man in the State, and Charlie Decker, the smallest man in the world, will be conveyed to the 4th Ward poll in a large wagon this morning so they can have a chance to cast their votes. We understand that a large procession will be formed, headed by a band to escort the extraordinary pair to the place of holding the election

…Let us all acknowledge that 19th century election days were more fun than our dreary doses of civic duty. Booze, bullying, bands, midgets, fat men and more booze…those were the ingredients for a joyous festival of democracy in the century before last.

One thing I want to highlight about this anecdote is the ability of a fat man to draw a crowd in the mid-19th Century. There are many newspaper paeans to the tastiness of Sam Riddleberger’s food and to his hospitality, but convivial fat men were also major attractions in and of themselves, to the point that John Riddleburger’s obituary in the Louisville Courier (November 22, 1905) suggested that the success of Riddleburger’s Eating Saloon was partly attributable to Sam’s adiposity.

His brother, Samuel Riddleburger, for years conducted a restaurant in Nashville, which got a lot of free advertising from the fact that Sam was probably the fattest man in Tennessee if not the South.

Fat men were especially prized before the Civil War. Unless you were a man of substance and leisure, it was very difficult to hit 300 pounds in the era before mobility scooters and processed cheese food. Hard physical labor, lots of walking and relative food scarcity and/or tastelessness meant that the average man rarely made it to 200 pounds. Those few who were over 300 pounds were noted, talked about and celebrated.

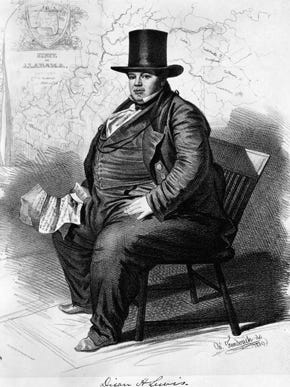

For example, Dixon Hall Lewis was a lawyer and congressman from Alabama who ballooned to 500 pounds while in office. Lewis’s official seat in the Senate was a custom-made, extra-strong, double-wide chair, from which he waxed eloquent about states’ rights. (According to the rules, you’re not officially a fat man until you’ve broken furniture.) Lewis reportedly broke the bottom out of a stagecoach, a story gleefully and often recounted by his enemies. The obese senator died in 1848 at the age of 46 while in Brooklyn, NY, visiting a weight-loss doctor.

One of the more popular lecturers in the 1840’s and 50’s, was the Reverend Henry Giles, a scrawny, hunchbacked, Irish-Catholic-immigrant-turned-Unitarian-minister whose humorous lectures on literature were well attended and widely reprinted. Here’s an excerpt from an 1844 lecture on Shakespeare’s Falstaff that sums up the general attitude to men of size.

There is something cordial in a fat man. Everybody likes him, and he likes everybody. … Food does a fat man good; it clings to him, it fructifies upon him; he swells nobly out, and fills a generous space in life. He is a living, walking specimen of gratitude to the bounty of the earth, and the fullness thereof; an incarnate testimony against the vanity of care, a radiant manifestation of the wisdom of good humor. A fat man, therefore, almost in virtue of being a fat man, is, per se, a popular man; and commonly he deserves his popularity. … A fat man has an abundance of rich juices. The hinges of his system are well-oiled; the springs of his being are noiseless; and so he goes his way rejoicing in full contentment and placidity.

It really does take a deal of wrong to make one hate a fat man; and if we are not always so cordial to a thin man as we ought to be, Christian charity should take into account the force of prejudice we have to overcome against thinness.

Or consider this anonymous filler item that made the rounds of the newspapers in 1849.

If I had to guess, I’d say that this is moment that gluttony ceases to be one of the Seven Deadly Sins in America.

You get a sense of how valued fat men were when you realize that Kentucky, alone, produced two 300-pound Civil War generals: the Confederacy’s Humphrey Marshall and the Union’s William “Bull” Nelson.

During the Civil War, even our fat friend Sam Riddleburger stuffed himself into a uniform. On August 25, 1861, the Nashville Republican Banner reported the elections of officers for the city militia. The men of the 3rd Ward picked E. A. Hicks as Captain, T.J. Blackman for 1st Lieutenant, Benjamin Lyon, 2nd Lieutenant and 37-year-old Sam Riddleburger as Ensign. Sadly, no photos remain.

Of course, by August of 1861, the real Nashville militia, The Rock City Guards, had already been converted into the Confederate Army’s 1st Tennessee Infantry Regiment and packed off to Virginia, leaving behind the infirm, decrepit and overly stout. So, it seems unlikely that Sam Riddleburger was called upon to defend the city in earnest which, in any event, wasn’t necessary, as the Confederates gave Nashville up without a fight.

On February 25, 1862, Federal troops under the command of Bull Nelson (see above) marched into Nashville unmolested, the city having been abandoned two days earlier by the Confederates. The citizens of Nashville were not especially hostile, in fact, Nelson was invited to tea by a prominent family, a repast that ended with Nelson stomping out, having literally thumbed his nose at his hostess. Meanwhile, one of Nelson’s subordinates, Brigadier William B. Hazen, checked into the St. Cloud Hotel, one block from Riddleburger’s, where…

We found in the hotel, fast asleep and very drunk, one Rebel soldier, the largest man I ever saw in uniform. As I sent him away with a single guard, he looked like a veritable giant guarded by a pygmy; and we all wondered if he was a sample of the men we were about to encounter.

I have no idea of the identity of this “largest man”, who sounds more tall than fat, however, what makes the incident curious is that, a month later, March 26, 1862, an advertisement for Riddleburger’s Old Stand appeared in the Nashville Daily Patriot announcing that Messrs. Kirby & Keel had…

…bought out the above named establishment and have newly fitted it up in good style. Their TABLES will at all times be supplied with all the LUXURIES of the season, and prepared in the best style. They hope the old patrons of the establishment and the public generally will give them a call.

Had Sam been captured at Nashville in 1862, or did he skedaddle? Or did he just need the money? I haven’t been able to figure it out one way or another. I can tell you that Riddleberger’s Old Stand was not always owned by Riddleburger. (More about this in a minute.) Whatever the case, Sam was back running his restaurant by the middle of 1863, when he submitted a substantial purchase request to the Union Army’s board of trade.

To the members of the military board of trade for the city of Nashville. The undersigned respectfully asks of your honorable body a permit for the following articles, (to wit)

6 bbls. bottled ale $175.00

10 baskets champagne wine $200.00

5 boxes of claret do. $30.00

10,000 cigars $350.00

4 sacks salt $15.00

S. S. Riddleburger

June 17th, 1863

Attached to the request was an affidavit signed by Sam on July 2nd, attesting to the fact that the ale, wine and cigars were for “use of restaurant”. At the bottom the page was a loyalty oath to the Union, which Sam subscribed.

Sam’s restaurant was a favorite of Union troops, we know this because it’s mentioned a few times in post-war memoirs as a place worth visiting. It even figures in one of the more odd events of the war, Abraham Lincoln’s expulsion of a notorious Copperhead.

Ohio congressman Clement Vallandigham was not a supporter of the Confederacy or slavery, just a principled man who believed that the Union should not be preserved by violence. The prominent Democrat had been a thorn in Lincoln’s side from before the war, but in May of 1863, Vallandigham went too far, gaving a speech in his home state in which he denounced the suspension of habeas corpus, complained about the conduct of the war and referred to the president as “King Lincoln”. He was arrested by military authorities, quickly convicted by a tribunal and sentenced to deportation from the United States. Writing in the November, 1909, issue of Confederate Veteran, Major Ben Truman, a Union man, recounted what happened when Vallandigham appeared in Nashville under military escort.

There were several pikes running south; so upon the arrival of the distinguished Copperhead I asked the Governor [Andrew Johnson] which way I should take him.

“Just as near to the smallpox hospital as you can,” answered Johnson ferociously. “But,” he added, “not near enough to endanger your escort.”

“When shall we take him?”

“This very night, confound him. We don’t want him here in Nashville; the Rebels would lionize him. Take him to old Riddleberger’s and give him some Robertson County whisky and a good supper and then set him a-going.”

Truman found Vallandigham to be a noble figure — “with the handsomest teeth I’d ever seen in a man’s head” — and a teatotaler.

When at the restaurant I asked for Robertson County whisky, he said: “But, my dear young friend, I don’t know what whisky is. I never drank any. When I started for college, my mother told me never to touch liquor, and I have never disobeyed my mother.”

At the end of dinner, the notorious Copperhead was sent south down the Granny White Pike, sober, into Confederate lines. Received as a hero, Vallandigham did not reciprocate Southern affection. He soon made his way to Bermuda and then onto Canada. The next year, still in exile, he ran for governor of Ohio and lost badly.

The end of the war did not initially bring prosperity to Nashville. The Union Army had provided enough customers to allow 13 restaurants and 109 saloons to do a lively business, but now the soldiers had gone home, and Sam struggled to make a go of things. In 1866 he introduced a prix fixe menu, only fifty cents for a meal, and fitted out rooms in the back of the restaurant as a hotel, advertising both things in newspapers throughout the region.

Competition for business was fierce. The newly refitted St. Nicholas Restaurant had a billiard room, a ten-pin bowling alley and a pistol range on the third floor, along with “Robertson County whisky old enough to vote at the next election.” (n.b. I told you 19th century elections were a hoot.)

Business picked up, and through the summer of 1869, Riddleberger’s was the probably the most important meeting place in Nashville. Only two blocks from the State House, businessmen, printers, politicians and other rascals frequented the restaurant, and the rooms upstairs were busy with the meetings of fraternal organizations and clubs such as the Nashville Blood Horse Association and the Davidson County Agricultural Club.

The sidewalk outside was widely known as “Riddleburger’s Corner”. In good weather Sam held court there, seated in a Dixon-Lewis-sized chair. (“The portly Riddleberger sits upon the sidewalk with his usual gravity.”) The corner was an open air lounge for “gentlemen of leisure”, who enjoyed nothing more than spirited political debate and impromptu displays of amateur pugilism. Inside, the dining room was frequently as lively. The high emotions of Reconstruction played out as Radical Republicans, Conservatives and Democrats drank their Robertson County whisky and exchanged sharp words. A large painting of Robert E. Lee on one wall was a target of both invective and adoration, and polite manners were not always observed.

Things seemed to be going well and then, in the middle of August of 1869, Sam got sick, very sick. The reports of August 12th didn’t specify what was wrong, just that Sam was “lying at the point of death”, adding, “there are no hopes of his recovery”.

But Sam did recover, although it took a while. We know that in the final years before his death he slept upright in a chair, probably suffering from chronic sleep apnea, one of the constellation of diseases that afflict the morbidly obese. Sam Riddleburger was only 45 years old, but 500 pounds are not lightly worn.

Unfortunately, 1869 was also the year that the Maxwell House Hotel opened up two blocks down Cherry Street. The hotel had cost more than $500,000 to build and taken more than a dozen years to complete (thanks to the Civil War). At its opening in October, the Maxwell House immediately became the preferred spot for fine dining in Nashville. Unlike Riddleberger’s Old Stand, with its manly atmosphere of rowdydow, knife fights and pistol whippings, the Maxwell House was a place you could safely take your wife, maiden daughters and mother-in-law.

At almost the same time, early fall 1869, the city authorities cracked down on the crime of “tippling on the Sabbath”. Several prominent hoteliers and restauranteurs, including Sam, were caught selling liquor to customers on Sundays. Sam pled guilty in a September court session, but at $50 an offense, it quickly added up. He was ordered to pay a total of $750 in fines by January of 1870.

By February of 1870, Sam was in real financial trouble. An advertisement in the Republican Banner announced that the clerk of the Chancery Court would auction off some of Sam’s bling.

One Round Diamond Cluster Breast Pin, with small Chain attached; one Chased Diamond Cluster Ring, and one Diamond Cluster Ring.

The jewelry was sold to satisfy Hugh Douglass, one of Sam’s creditors. That year and the next, there were more lawsuits, a few thousand dollars worth, and by the fall of 1870, Sam was out of business. A few months later, in early 1871, newspapers announced that the Ambrose Brothers, rival restauranteurs of long standing, had outfitted a new restaurant in the old Riddleberger space.

After that, Sam seems to have headed to Louisville, because the next time we see him in the newspapers it’s as the subject of a distressing rumor, dated July 22, 1871.

There was a rumor in the city last night, which we could trace to no reliable source, that Sam Riddleberger had died yesterday at Louisville.

But, once again, Sam did not die, instead, he retuned to Nashville and in January, 1872, an advertisement in the Nashville Union & American announced…

BACK TO FIRST PRINCIPLES.

Sam Riddleberger,

The Well-Known Restauranteur, in the Field Again.

Back in the field, not at his own restaurant, but as the manager of the Merchant’s Exchange Restaurant. Business wasn’t good, or Sam got sick again, because by the end of the year a new manager had taken his place. The next few years are hazy, probably because Nashville and its restaurants were experiencing the first waves of the coming economic depression.

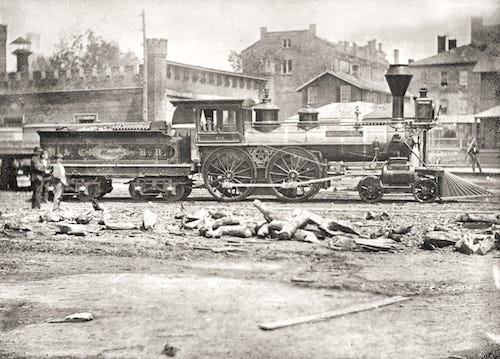

Nashville wasn’t ground zero for the Panic of 1873, but it wasn’t far off. The city was a major railroad town, and it was a railroad investment bubble that popped in the fall of 1873. You can actually see the collapse coming in the Nashville newspapers earlier than that. For example, on the day after Sam was rumored to have died, in July of 1871, the Alabama and Chatanooga Railroad reported that one of its steam engines had been “stolen at Tuscaloosa”, driven away down the Meridian line, “by a band of twenty-five or thirty men. No one knew who the party was.”

The locomotive rustlers were creditors. Engine 19 hadn’t been stolen, so much as repossessed, the A&C RR having defaulted on its bond payments earlier in the year.

In Nashville, over the next couple years, restaurants closed and hotels failed. During 1874, in the depths of the depression, Sam opened another Riddleberger’s Restaurant at 76 Church Street and seemed to thrive. At almost the same time, the Ambrose Brothers closed their restaurant in Sam’s old space and sold the fixtures, setting up a chance for Sam to return to Riddleburger’s Corner. But first…

From the Columbia Herald and News, February 5, 1875.

Tin Chappell interviewed Riddleburger the other day an obtained these interesting facts: He is 51 years old; weighs 296 pounds; the most he ever weighed was 523 pounds; he fattened 160 pounds in the year 1864; at one time he came near suffocating with corpulency; and the doctors reduced his weight 173 pound in five days, during which time he was unconscious. He said he was always hungry, but did not eat but twice a day, and chewed tobacco incessantly.

I have no idea how doctors could have reduced Sam 173 pounds in five days, short of cutting off both legs. In repeating this story the editor of the Memphis Appeal suggested that Tin Chappell — a.k.a. Dickey Tinsley Chappell, a wag who owned a livery stable in Columbia — was “liberal in his imagination”.

By the next year, 1876, Sam was back in business at his old spot, doing a brisk trade.

Unfortunately, less than one month after this advertisement and Sam was dead. He caught a cold during Christmas week that turned into pneumonia and killed him on the 6th of January, not exactly suffocated by corpulency, but not far off.

The next day, Sam’s partner, Oliver Towles assured Nashvillians that Riddleburger’s Restaurant would continue under the name of its founder. Two days later, the paper reiterated Towles’ assurance, adding…

Mr. Towles has practically had the management for some time, during the indisposition of the late Mr. Riddleburger. His enterprise and energy in the conduct of it will be ample guarantee that it will lose none of its ancient prestige as a first-class restaurant.

Sam had obviously been sick for a while and he weighed 475 pounds at his death. If you accept Tin Chappell’s report of February, 1875, Sam had gained almost 180 pounds in two years, a prodigious and prodigiously self-destructive feat of gluttony for a middle-aged man.

Oliver Towles did his best, and although it changed hands at least three times, Riddleburger’s stayed in business until 1882. Without Sam Riddleburger, however, “the embodiment and illustrator of good living”, Riddleburger’s was just another restaurant.