Taming the Wild Auroch, Bull Dancing, and the Beef-Eating Greeks

An excerpt from the first book of the Iliad:

His prayer went up and Phoebus Apollo heard him. And soon as the men had prayed and flung the barley, first they lifted back the heads of the victims, slit their throats, skinned them and carved away the meat from the thigh bones and wrapped them in fat, a double fold sliced clean and topped with strips of flesh. And the old man burned these over dried split wood and over the quarters poured out the glistening wine while young men at his side held five-pronged forks. One they had burned the bones and tasted the organs they cut the rest into pieces, pierced them with spits, roasted them to a turn and pulled them off the fire. The work done, the feast laid out, they ate well and no man’s hunger lacked a share of the banquet. When they had put aside desire for food and drink, the young men brimmed the mixing bowls with wine and tipping first drops for the god in every cup they poured full rounds for all. And all day long they appeased the god with song, raising a ringing hymn to the distant archer god who drives away the plague, those young Achaean warriors singing out his power, and Apollo listened, his great heart warm with joy.

One of my all-time favorite classes to teach is something I’ve given the title “Loyalty, Honor and Violence in Homer’s Iliad”, which while being well out of my area of expertise still makes my great heart warm with joy.

The only required text is the Iliad in Robert Fagles magnificent translation and all we do is sit around and read it out loud to each other. And if everything goes well, by the end of the semester, two things will have happened: we will have read about 80% of the epic out loud in class, and the majority of the students will tell me that it was one of the best, if not the best, class they’ve ever taken.

The secret to the whole project is that I add historical, artistic and literary context as we go along, stopping the reading for a few minutes, making some observations and inviting conversation. So for example, at the end of the sacrifice scene quoted above — the famous hecatomb made when Agamemnon’s men return Chryseis to her father — I talk about the nature of sacrifices in the ancient world. One of my goals is to get students to make the conceptual connection between ancient animal sacrifice and the death of Christ and the Eucharistic feast. Doing this puts those two things back into the historical context in which they occurred. So, students now understand that when Jesus takes up the bread and says, “take, eat: this is my body”, everyone at the table, Jew and gentile, knows what’s going on, because everyone is familiar with what happens at an animal sacrifice, as it’s a very common thing. The great temples of the Near East and the Mediterranean were emphatically places where blood was shed, to the point that one wag has called the altar in the Second Temple in Jerusalem, Jehovah’s “barbecue pit”, and another has referred to the Oracle of Delphi as a “great and ever active slaughterhouse.”

My other goal when discussing this scene is to point out nimal sacrifice meant eating meat, usually lamb and goat, but for the big sacrifices, beef and lots of it. Most people, not just students, don’t know that the burnt offerings given the divine guest of honor were not the choicest cuts, but rather the fat, bones and offal, essentially the variety meats we grind up and cram into wiener casings. The good stuff, the ribs, steaks and rump roasts, were reserved for the mortals, usually preceded by an appetizer of grilled kidneys, liver and chitterlings, skewered and roasted over the sacrificial fire.

There is much, much more that can be said here about the sacrifice and consumption of animals in Ancient Greece. Classicists have written books about the topic, and their scholarly debates will likely never end. I, however, am intrigued by all of that beef roasting on those Homeric spits, and choose to leave the arguing about details to the detail minded.

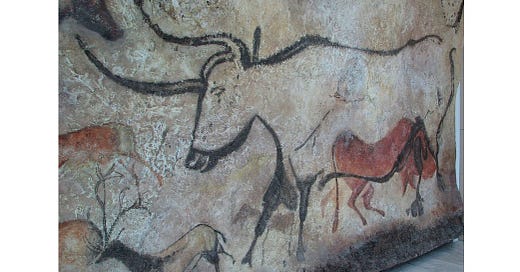

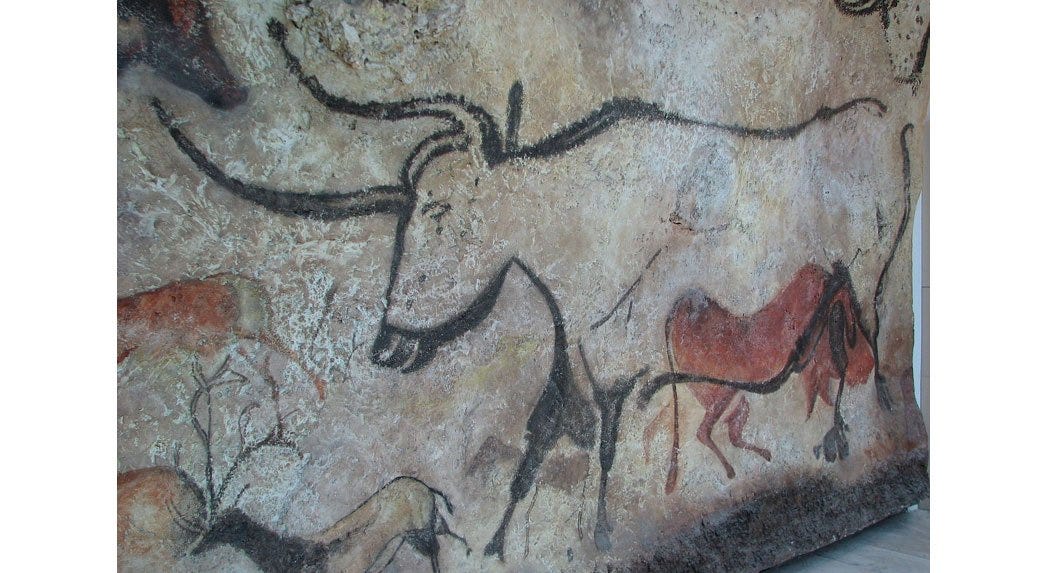

One of the topics we sometimes detour into in my class is the domestication of the auroch, a process that must have been harrowing for the neolithic humans who tried to do it. The auroch is the wild predecessor of the domesticated cow, a nearly ubiquitous beast that once roamed a swath of North Africa and the Eurasian landmass, from Spain to Central Asia and down into India. It was also the last of the major animals to be domesticated, coming into the human sphere probably around 10,000 to 8,500 years ago, and one of the first to be eaten completely into extinction, the last one having died in a Polish game preserve in 1627.

Although small sample size, preservation and a dearth of older individuals with inhibited mobility may contribute to the Neandertal lesion distribution, the similarity to the Rodeo lesion distribution suggests frequent close encounters with large ungulates unkindly disposed to the humans involved.

Scientific understatement is the best understatement.

The average Professional Bull Riders athlete has a 1-in-15 chance of being injured each time he mounts the bull in the chute. We don’t know the odds for the paleolithic hunter, but we do know that the Neanderthals mostly hunted by ambush, in close with thrusting spears, possibly while one of their number grabbed onto the animal, often a woolly mammoth, and held on while it thrashed about.

When the climate warmed and the hairy megafauna of the Ice Age disappeared, the Neaderthals followed them into extinction, out-competed by his smaller, weaker rival, us. We had throwing spears and our prey was smaller (6,000 pound woolly rhinos no longer roamed the forests of ancient France), but there are few things that taste as good as grass-fed beef, and so we continued to hunt the biggest game we had, the auroch, even as we domesticated the pig, the dog, the sheep and the goat.

As I said, the initial domestication of the auroch must have been a harrowing and difficult thing. We know this because modern taurine cattle, the European kind, are descended from very few ancient animals, around 80, who were domesticated by farmers, not nomadic herdsmen, over a couple thousand years in a small region in the mountains of Turkey and Iran. There was a separate domestication of the Indian zebu cattle, the humped kind, about 2,000 years later in the Indus Valley, and possibly a third domestication in Africa. The DNA nabobs are still trying to figure all of this out.

The reason that cows were domesticated by farmers and not nomadic herdsmen, who had tamed the pig, dog, goat and sheep, is because you have to keep your wild auroch breeding stock penned up, lest it kill you. The auroch was famously aggressive. Here’s Julius Caesar writing about them in his Commentary on the Gallic Wars.

There is a third kind [of wild animal], consisting of those animals which are called uri. These are a little below the elephant in size, and of the appearance, color, and shape of a bull. Their strength and speed are extraordinary; they spare neither man nor wild beast which they have espied. These the Germans take with much pains in pits and kill them. The young men harden themselves with this exercise, and practice themselves in this kind of hunting, and those who have slain the greatest number of them, having produced the horns in public, to serve as evidence, receive great praise. But not even when taken very young can they be rendered familiar to men and tamed.

Is it any wonder than, that our Indo-European ancestors revered the bull, worshipping it as a deity, sacrificing it to their gods, and testing themselves against it’s wild ferocity. That last statement is the final classroom digression, humans tested themselves against the wild bull, and they still do.

We’re all familiar with this image from the island of Crete, circa 1700 BC.

There’s a straight line from that image to this image from Madrid, Spain, circa 2014 AD..

Other than costume there is little difference between what those young Minoans are doing and what that young Spaniard is doing. He’s a recortador, a bull jumper, and like the more famous and glamorous bullfighters, the toreadors, he’s testing himself against that dangerous, deadly animal.

And it is a dangerous and deadly and animal. The Spanish toro bravo is not a placid domesticated beeve of the of sort that crushed Lyle Lovett and hundreds of elderly farmers. It’s a wild thing, bred for size, speed and peevishness. It rarely sees humans, and never a man on foot, until it’s taken from the giant ranch on which it was raised and brought to the arena. There, young men will expose themselves to its rage. (Stick with this video below for a few minutes, it gets better as it goes along.)

YouTube is filled with hundreds of these man-versus-bull videos, of Spanish recortadores and toreadores, Gascon French écarteurs and sauteurs, Portuguese forcados, and American and Brazilian bullriders. And just like the Minoans, there are even a few brave women who dance with bulls in Spain and France.

If you watch enough of these videos, not very many, you’ll eventually see men killed or injured, some grievously so. In 2011, the Spanish bullfighter, Juan José Padilla stumbled in the ring, and was gored, the horn going under the jaw and out the left eye socket. The bull dragged him for several yards before it let him go, leaving him blind in the left eye, deaf in his left ear and, after several surgeries, with a skull full of titanium plates and screws, and a face fully paralyzed on the left side. Yet, within six months, Padilla was back in the ring fighting bulls, a black eyepatch firmly affixed to his mauled face.

Think of this the next time you enjoy a steak cooked over split wood in the ancient Greek style, of how the second greatest achievement of our neolithic ancestors, after agriculture, was the conversion of the auroch into dairy cows and draught oxen. Of how the primal fear of this horrible beast, bred into men over millennia by ten thousand deaths on its horns, persisted in our racial memories, side-by-side with the driving desire to master the animal, to make it our servant in civilization. This is why Juan José Padilla was drawn back into the arena, because there the ancient drama is played out again, as it was in Knossos four thousand years ago, or in Sumer two thousand years earlier when Gilgamesh killed the Bull of Heaven. It is the essential drama of civilized man against nature: the retaming of the wild auroch.

P.S. If you like this post, please share it on Facebook or Twitter. I think it’s one of best pieces I’ve written in a while and would like to have more people read it.