Sympathy…

One thing I try to teach my students is that to be a good historian, you have to have some sympathy for the people of the past. You have to try to understand what motivates and moves them on their own terms, even while you might be inclined to laugh, scorn, or be angered by them.

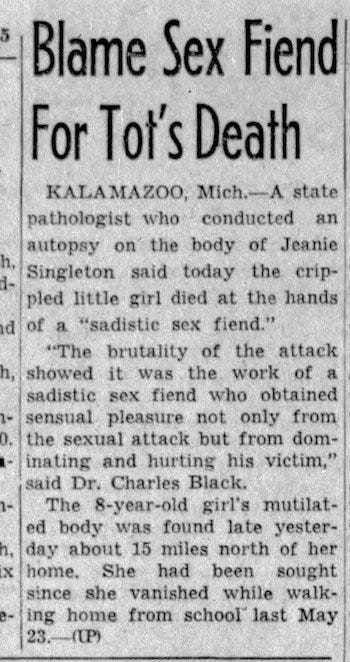

Take, for example, this letter to the editor, written 70 years ago by Mrs. Norma Thomas of Merced, California. If you’re like me, your first inclination is to chuckle at the phrase “sex fiend”, it being both old fashioned and somewhat ludicrous, the sort of phrase that smart people made fun of in the 1970s, during the era of sexual liberation and license.

Language changes, right? Words and phrases come in and go out of fashion, the old terms being replaced by newer, shinier words. And because the old language gets discredited, we thoroughly modern geniuses are tempted to laugh at the panicky hausfraus of 1955. But, maybe, if you were historically minded, you might also want to try to figure out what was bothering Norma Thomas.

Two horrifying stories in California newspapers in June and July of 1955, stories that help us understand that, in the 1940s and 50s, “sex fiend” was the phrase most commonly used to describe what we might call a “sexual predator”, or even a “serial killer”.

As far as I can tell, having searched the archives of Central Valley newspapers, this is the only letter to the editor Norma Thomas ever wrote, evidence that she was powerfully agitated by what she was reading in the newspapers. But she was not the only one. Letters expressing worry about “sex fiends” were common that summer in newspapers across the country, proof of a wider moral panic kicked off by stories like the two above.

Curiosity…

I also tell my students that a historian must have the logic, tenacity and curiosity of a great detective, because historians, like detectives, try to answer questions about past events.

So, now, having read Norma Thomas’s letter to the editor and those two terrible stories, your curiosity should be engaged. Why? What was happening in America in the decade after the Second World War that brought on this moral panic about sexual predators? Were there actually more sex crimes in the 1950s than in previous decades?

One thing we can say, is that 1955 was a remarkably safe year in America, with a homicide rate more than half of what it had been just 20 years earlier.

So, what was going on? Crime rates were sharply down, but emotions were up? Why?

As historians, we’re taught to prefer primary sources when considering causality. Here’s one, again from the Fresno Bee, July 29, 1955.

That’s one potential answer to the question, provided by Alice Ketcher: women were wearing more revealing clothing, thus inciting “sex fiends” to act out. And while I might be tempted to dismiss this with another chuckle, as a historian who tries to be sympathetic, maybe I shouldn’t.

Fashion reflects society, and more revealing clothing, while perhaps not causative in the way Alice Ketcher claims, may nonetheless reflect changing attitudes about propriety and sex, changes that leave some people morally disturbed and lead others to believe they have license to do things they shouldn’t.

Perhaps, another reason for moral panic might be that, after World War Two, newspapers were more explicit in their descriptions of sex crimes. Before the war, rape was more likely to be described in veiled terms, such as “violated” or “outraged”. After the war, details were not spared. The two clippings I pasted above are much more circumspect in describing the condition of the bodies than stories found in other newspapers, many of which were sickeningly graphic.

The question now is, are the newspapers responding to a public that wants more sensational material? If we’re building a case for that, I’d remind you that film noir peaked as an artistic genre in the 1950s, and the violent crime novels of Mickey Spillane were huge bestsellers, indicating a wider taste for explicit stories about criminal brutality and moral ambiguity.

Speaking of movies about criminality, what does it say about changing attitudes that one of the biggest hits of 1934 was Little Miss Marker?

If you don’t know, the film stars Shirley Temple as a young girl left with her father’s bookie, Sorrowful Jones, as a "marker", collateral, for her father's gambling debts. When her father commits suicide, the gruff Sorrowful and his colorful gang of crooks and ne’er-do-wells reluctantly take her in, only to be charmed and transformed by her spunky innocence.

Get that? At the height of the Great Depression, people believed that small children could be safely left with degenerate gamblers and criminals, this despite the fact that child murders were not especially rare, and the homicide rate twice as high as it would be in 1955. In fact, it’s only twenty-one years from Little Miss Marker to 1955, but the world seems radically different.

Finally—not finally, there is no finally in writing cultural history of this sort, only more threads to pull at—you’ve got to consider the possibility that an entire generation of Americans has been traumatized by World War 2, young men directly in combat, young women indirectly, while waiting for news of their classmates and lovers, many of whom never returned.

To go back to the writers of our letters, a little digging shows that in 1955, Norma Thomas was 31 years old and Alice Ketcher was 66. Norma Thomas was of that WW2 generation and had small children at home. She wasn’t complaining about skirt lengths, she was terrified (justifiably or not) for the safety of her children, just as she might once, a decade earlier, have been terrified for the safety of her brother, young husband or high school sweetheart.

Finally, not finally, the reason I say that there is no “finally” when doing this sort of cultural history is that history, like real life, is enormously complex and our sympathy and curiosity necessarily finite. We have to prioritize what we consider important when weighing causality. Pull at one thread and you loosen another—crime, fashion, journalism, movies, war and trauma are all tangled up together, each helping us understand a specific moment in American history, each helping us answer a specific question: Why was Mrs. Norma Thomas of Merced, California, so agitated?

I’ll be back next week with another post. See you then!

Fascinating. Wish I could take a history class from you. May I offer my own historical perspective from having lived and worked in the media world? The media has always censored, promoted and filtered what they serve up to their readers. They want to sell papers. I also never completely trust letters to the editor since as a child in the 60s I knew a famous gossip magazine editor, who was my dad's client. His letters section was incredibly popular. His way of ruining a career by saying an actor was gay was by responding to a supposed letter to him about an actor by saying “He's good to his mother.” The question to ask at any time is “why is this news being printed?” Right now, if you do a search on Trump, it's unbelievable what cones up. No articles or video links to what he's actually done in the last week. Here's Victor Davis Hansen on it https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CzCVELIL1rY. So 30 years from now, will historians believe the media accounts actually reflect something about our era?

As one historian to another, this is the sort of thing that people *have to get*. They may not, but analysis of this sort leading to an “it’s complicated” is the real work.