Nixtamalization is the first step in making a tamale, a taco, or hominy. It’s a 3,000-year-old method of removing the pericarp, that thin outer layer, from a kernel of corn. Dried corn is soaked in an alkaline solution, a soup of water and wood ashes, slaked lime, or lye, for a few hours, rinsed in cold water and rubbed. The pericarp either dissolves or slips right off.

What’s amazing about nixtamalization is that it doesn’t just remove the pericarp, it significantly changes the chemistry of the endosperm, the starchy innards of the kernel, making it better tasting, more easily ground, and capable, with the addition of a little water, of being worked into masa, the basis of tamales, tortillas and almost every other corn-based Mexican delight. American cornbread is made with a cornmeal batter because un-nixtamalized corn lacks the emulsifying agents necessary for binding.

The other great advantage of nixtamalization is improved nutrition. A diet high in unnixtamalized cornmeal can result in the deficiency diseases pellagra and kwashiorkor, a lack of niacin in the first case, and insufficient protein in the second. Steeping dried corn in a solution of lye, wood ashes, or calcium hydroxide (lime) releases niacin from the kernel and produces amino acids needed to help process protein, especially those found in beans. So, make your succotash with hominy. Because of nixtamalization, pellagra has almost never appeared in Mesoamerica, and in fact the development of nixtamalization, sometime around 1500 BC, probably allowed for the expansion of populations and civilizations in the Americas in the pre-Columbian era, as maize could now be relied upon to form the foundation of a nutritious diet.

Nixtamalization didn’t just just improve nutrition, the masa-based cuisine that developed in Central America was also, in the words of the 16th century Spanish priest, Bernadino de Sahagún, “tasty–tasty, very tasty, with a pleasing aroma”, and was blessed with an astounding variety of dishes.

He sells meat tamales; turkey meat packets; plain tamales; tamales cooked in an earth oven; those cooked in an olla… kernels of corn with chile, tamales with chile… fish tamales, fish with kernels of corn, frog tamales, frog with kernels of corn, axolotl with kernels of corn, axolotl tamales, tadpoles with kernels of corn, mushrooms with kernels of corn, prickly pear cactus with kernels of corn, rabbit tamales, rabbit with kernels of corn, pocket gopher tamales: tasty—tasty, very tasty…with a pleasing aroma…Where [it is] tasty, [it has] chile, salt tomatoes, squash seeds: shredded, crumbled, juiced. He sells tamales of corn softened in wood ashes, the water of tamales, tamales of corn softened in lime—narrow tamales, fruit tamales, cooked bean tamales; cooked beans with kernels of corn, cracked beans with kernels of corn. [He sells] salted wide tamales, pointed tamales, white tamales, fasting foods, roll-shaped tamales, tamales bound up on top, [with] kernels of corn thrown in; crumbled, pounded tamales; spotted tamales, pointed tamales, white fruit tamales, red fruit tamales, turkey egg tamales, turkey eggs with kernels of corn; tamales of tender corn, tamales of green corn, brick-shaped tamales, braised ones; plain tamales, honey tamales, bee tamales, tamales with kernels of corn, squash tamales, crumbled tamales, maize flower tamales.

American consumers of Mexican food are rarely given a chance to eat pocket gopher tamales, much less bee or tadpole tamales, as appetizing as those may sound. However, we should admire the ingenuity of ancient Mesoamerican cooks, and their ability to fully use what nature provided.

Corn was introduced to Europe sometime shortly after Columbus returned from his first voyage, and spread from there with a shocking rapidity. By 1500 the first corn crops were being harvested near Seville, Spain. A little over a decade later, in 1513, maize was being grown in China. Unfortunately, the nixtamalization process wasn’t brought back with the corn, which was bad, because corn offered a number of significant advantages over traditional Old World staples like wheat: a shorter growing season, high tolerance for all sorts of climatic conditions, and yields that were three or four times greater. Because of these advantages, especially the greater yields, corn, together with potatoes, another nearly miraculous New World crop, became the peasant staples of Europe.

The increase Europeans’ daily caloric consumption caused by the addition of New World crops to Old World diets allowed Europe’s population to explode, contributing to the rising dominance of the continent in the early modern period. But, larger populations brought greater economic pressure, pushing more people into poverty. Pellagra began to appear in the mid 18th century in the peasants of Spain, Italy and southern France. It’s main symptom is a terrible case of dermatitis, horrible red lesions and itchy skin across the body, accompanied by diarrhea, listlessness, and eventually dementia. It was fatal nearly 2/3rds of the time.

Corn was one of the cheapest and most easily grown crops, and the poor in Spain and Northern Italy largely subsided on a diet of cornmeal mush, i.e. polenta. The equally impoverished Irish peasants escaped pellagra by the simple fact that they didn’t like corn, preferring their potatoes, a preference that brought its own problems in the 1840s when the Potato Blight destroyed that crop.

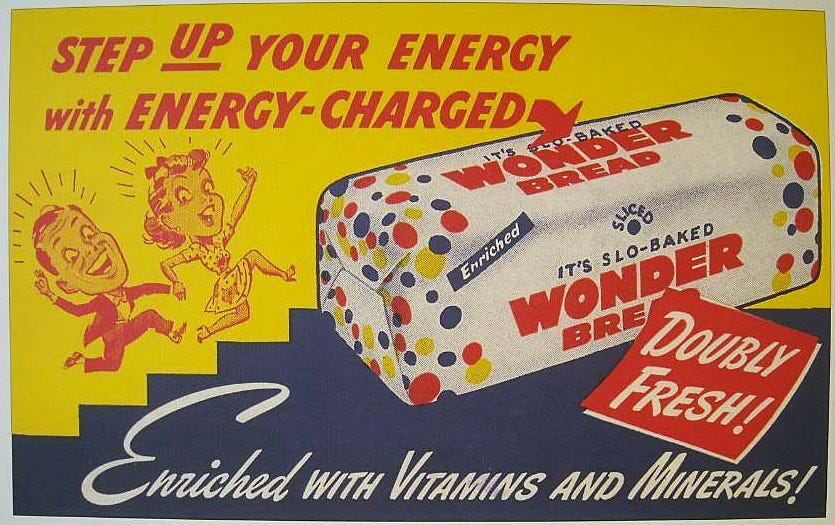

In the United States, during the first four decades of the 20th century, as many as 100,000 people, mostly Southern sharecroppers and from niacin deficiency, from pellagra. This epidemic was caused by a combination of factors, mostly the decline in the price of cotton, which forced sharecroppers into more desperate poverty, reducing their diets to just cornbread and pork. Another factor was the invention of better milling techniques for corn and wheat, such as roller-milling. Roller-milling wheat produces a reliably uniform, refined white flour, making it a baker’s dream for consistency, unfortunately it also removes most of the nutrients, including 80 to 90% of the niacin. After the link between niacin deficiency and pellagra was discovered in 1937, industrial millers and bakers began enriching flour with nutrients. This brought about something referred to as the “Quiet Miracle“, the disappearance of nutritional deficiency diseases in America in the post-war era.

There’s another reason to favor nixtamalization, which is taste. Nixtamalization can turn a cheap field corn, like yellow dent, into a perfectly tasty, tasty, very tasty masa. In fact, sweet corn, the kind we usually favor for table eating in the US, doesn’t work well for masa because it lacks the starchiness of dent corn, and is picked earlier in the life cycle, in the immature “milk stage” rather than the fully ripened “dent stage”. But, beyond that, as Dave Arnold says in an exhaustive post on nixtamalization at Cooking Issues

Nixtamalized corn has an amazing aroma and flavor, which is why a tortilla doesn’t taste like plain cornmeal.

And that’s what it’s all about, isn’t it? Once you make sure you’re getting your basic nutrients, why not concern yourself with the taste of what you’re eating.

Unfortunately, the food industry is only secondarily, or tertiarily concerned with taste, preferring to focus on efficiency, reduced cost and long term storage qualities. For consumers, convenience and cost also frequently trump taste. As a result, almost all commercially available masa is now prepared using an industrial process called enzymatic nixtamalization, in which corn is briefly soaked in an alkaline solution containing protease enzymes. Instead of eight to twelve hours of soaking, only 30 minutes to an hour are needed, during which the enzymes partially digest the pericarp. In addition to less time, the process also saves water and reduces the amount of alkaline waste water, nejayote, discharged by the plant. These latter benefits are good, but they come at the cost of taste. Masa produced in this manner just doesn’t taste as good as masa prepared in one of the traditional ways. Which is why all over the internet you’ll see people experimenting with do-it-yourself nixtamalization…

I think the best, and most comprehensive of these attempts at DIY nixtamalization is Dave Arnold’s four-year-old post from Cooking Issues, which I mentioned above. The Mother Earth News also has a good version of the process using food grade lye, and is taken from Anthony Boutard’s 2012 book, Beautiful Corn. My biggest complaint about both of these versions is that they don’t try nixtamalizing corn using wood ashes, perhaps the original method of processing corn, one that was widely used by the indigenous people of North American, and is still used by the Hopi and Navajo today with juniper ash.

Obviously, corn nixtamalized with wood ash has a different flavor from that nixtamalized with cal, slaked lime, why else would Fr. de Sahagún’s Toltec tamale man sell “tamales of corn softened in wood ashes… tamales of corn softened in lime,” unless his customers expressed a preference for one flavor or the other.

There’s plenty of evidence of the superior flavor of of wood ash nixtamalization, such as this excerpt from Thomas Robinson Hazard’s 1878 book, The Johnny Cake Papers of “Shepherd Tom”

Then again there was samp—coarse hominy pounded in a mortar—and great and little hominy, all Indian dishes fit to be set before princes and gods. But what shall I say of the hulled corn of old? None of your modern tasteless western corn, hulled with potash, but the real, genuine ambrosia, hulled in the nice sweet lye made from fresh hard oak and maple-wood ashes. I remember when a bowl or porringer of hulled corn and milk was a thousand times more relished by me than any dish I can now find at any hotel in the United States.

Hazard’s statement has the savor of a cranky old man telling us that things were better back in the day, but it’s probably correct. It seems likely that the tastiest masa or hominy is produced via wood ash nixtamalization, rather than slaked lime, especially if it’s to be eaten alone, as bowl of hominy or grits, rather than as a base for other flavors, such as as a tortilla wrapped around a filling.

Of course, some one now needs test this thesis by doing head-to-head tastings of corn nixtamalized with lime and with wood ashes. They should be sure to try a few varieties of wood ash–juniper, oak and maple at the least.

Finally, I’ve been mildly obsessed with nixtamalization for the past couple of months, ever since I learned that the mote in the Chilean drink mote con huesillos was nixtamalized wheat, a fact which makes an already strange beverage even stranger and more wonderful. But that’s a topic for a later post.

What a wonderful article , beauty in the eyes of the beholder, and one desiring the original, and more natural process of nixtamalization with wood ash.

I live in rural western Piedmont, North Carolina on land with many different hardwoods and just as you have mentioned, have a desire to experiment with what wood ash imparts what taste and nutrition.

I found an old paper that listed mineral content of various woods in North Carolina, with eastern dogwood, redbud and tulip poplar having the highest mineral content thou the list was not very inclusive.

The experiment has just begun , I have a small dedicated woodstove . I will burn different woods, using fine wood shavings for kindling and no paper, cardboard, or other artificial starters for clean ash. Any more wood ash information you might have I would greatly appreciate if you would share and I will do the same as I make progress in this experiment..

I’m happy I found your article. Thank you, Respectfully Hunter