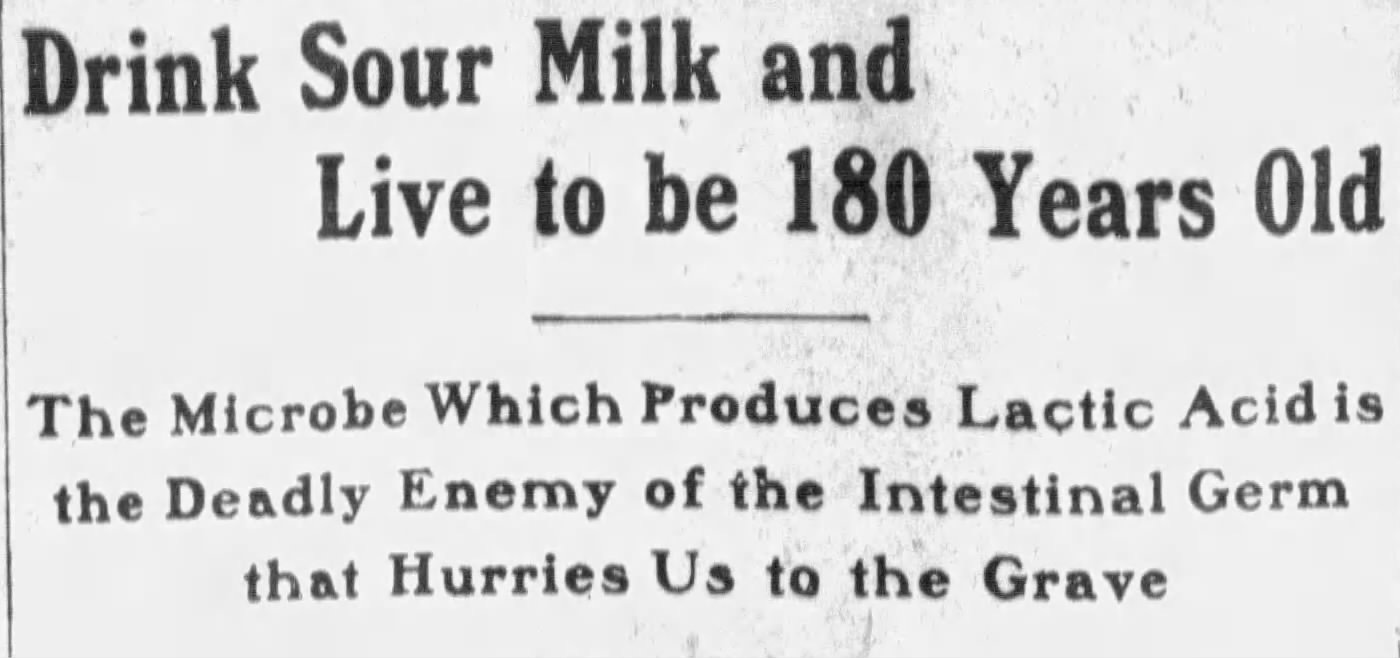

A little over a century ago Americans discovered yoghurt for the first time, mostly thanks to a Russian scientist and future Noble laureate who believed that senescence was a disease, not a natural part of life. Dr. Élie Metchnikoff, a senior researcher at the Pasteur Institute in Paris, was convinced that lactobacillus, the microorganism that ferments milk into yoghurt, was capable of retarding the onset of old age by eating the bad bacteria that caused us to grow old before our time.

[Sour milk] is supposed to be death to all the inimical bacteria in the intestines, while those friendly microbes to which Prof. Metchnikoff pins his faith positively adore it. Hence, the property of yaghurt to prolong human life to what is its normal span—a century or so. The substance looks very like ordinary cream cheese gone bad, and tastes similarly. The solid portion is mixed with a white, thin liquid, which is exceedingly sour. People who wish to live to a hundred breakfast off of yaghurt exclusively.

~The Washington Post, June 17, 1905

Newspapers were quick to point out that wasn’t just any old curdled milk that did the anti-aging trick, only that produced by the bacillus Bulgaricus was specifically identified by Metchnikoff as being efficacious. Thus, Bulgarian yoghurt became the super food of its day, and Metchnikoff is credited with inventing both gerontology and probiotics.

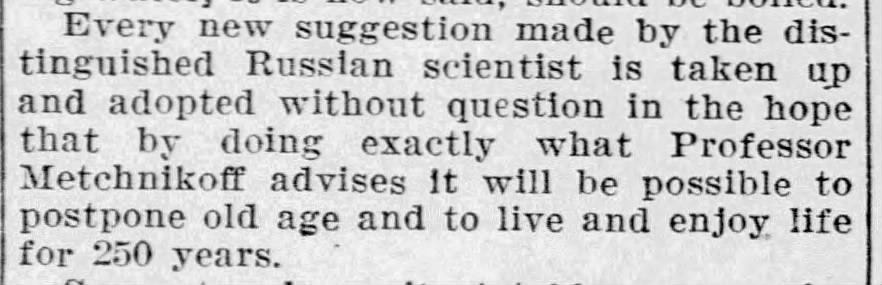

Oddly, even before Professor Metchnikoff had started touting yoghurt, Americans had already accepted that Bulgarians were the longest-lived people on planet Earth. In 1896, a German statistician had determined that there were 3,883 centenarians in Bulgaria, meaning that a remarkable 1 out of every 1,000 Bulgarians was over the age of 100, or six times the rate of 21st century America, where only 0.173 of 1,000 are centenarians. According to the Oakland Tribune, in Bulgaria, centenarians were as “common as huckleberries,” and the three oldest of these huckleberries were said to be between 135 and 140 years old.

Why Bulgarians were so long-lived could only be attributed to their habit of chugging heroic quantities of yoghurt at every meal of the day. Or so, Dr. Metchnikoff and the newspapers proclaimed.

Unfortunately, reports of Bulgarian longevity seem to have been greatly exaggerated. Indeed, the best current guess is that Bulgarian life expectancy at the turn of the last century was actually only 40.08 years, more than a few decades short of a century. As with Sardinians and Okinawans more recently, Bulgarians were better at convincing outsiders they were very old than actually being very old.

Be that as it may, Bulgarian yoghurt soon became a staple on the breakfast tables of middle-aged Americans. Those lucky enough to live in industrial cities, like Pittsburgh, St. Louis or Buffalo, could purchase their life-giving curdled milk directly from Bulgarian restaurants. (In some American cities, there was a surprisingly wide-variety of Mitteleuropean restaurants at the turn of the last century.) Those who didn’t have access to Bulgarian fine dining could either make their own yoghurt, using tablets of bacillus Bulgaricus and warm milk, or buy yoghurt from a local drug store or dairy. For example, in Montana and Idaho, yoghurt was sold under the trade name “Idalac”.

In the first decade of the 20th century, gulping yoghurt became a certified fad. By 1908, it was estimated that New Yorkers were drinking half a million quarts of yoghurt a week.

At every soda water fountain, where formerly youth and beauty gathered for no more scientific purpose than to quaff sweet-flavored drinks and fish for ice cream in the depths thereof, there are scores of enthusiasts drinking soured milk. In saloons the “demon rum” has a potent rival in this same soured milk and buttermilk. To drink it is to show oneself up-to-date, well informed as to the recent discoveries of science, and on every hand there is a vague idea not only that it is “good for what ails you,” but that it makes one live long.

~Camden Morning Post, August 27, 1908.

It should be noted that Dr. Metchnikoff wasn’t some random Dr. Oz, peddling snake oil and bottled sunshine, but a real scientist working in a real laboratory at what was then the cutting edge of knowledge. He did, after all, win the Noble Prize for medicine in 1908 for his discovery of phagocytes, the cells that defend the body from all sorts of nasty things. His belief in the heath benefits of probiotics wasn’t exactly wrong, just vastly overstated, and all those people gulping down yoghurt were simply “following the science.”

Like all dietary fads, the yoghurt fad played itself out in a few years, probably helped along by the death of Dr. Metchnikoff in 1916 at the unexceptional age of 71. So, yoghurt fell out of fashion and didn’t really return to American consciousness until after World War II, when the Dannon brand arrived from Europe and started putting fruit into the bottom of their yoghurt, making it sweet enough for American palates. Yoghurt was again sold using dubious claims that it promoted long life, although, to their credit, Daniel “Dannon” Carasso, the CEO for whom the brand was named, did live to be 103 years old.

P.S. For some reason, I’m greatly amused by the various spellings of yoghurt in turn-of-the-century American newspapers: zoghurt, zogburt, yahourth, yoghourt, yagburt, yaghurt, and yaourt all appear in one place or another.

Thanks for reading. Be sure to follow me on Twitter and Instagram, and share this article with your friends. See you on Thursday with something new.

Great piece. Love this coulmn.